John G. Niehardt

Koi Garden Plaza

Branson, Missouri

By Matt Miller

Aside from his work as the editor of Black Elk Speaks, the poet John G. Neihardt is best known as the perpetual poet laureate of Nebraska — the legislature conferred that title upon him in 1921 and never retracted it, requiring later appointees to accept the lesser title of “state poet.” At the time of that commission, however, and for much of his life afterward, Neihardt in fact lived in Branson, Missouri, near the edge of the White River.

Neihardt remains quite a presence in Nebraska despite his departure from the state. A well-developed state historic site on the site of his former home in Bancroft offers education on Neihardt and Native American culture, and various structures (a park, an elementary school, a residence hall) bear his name.

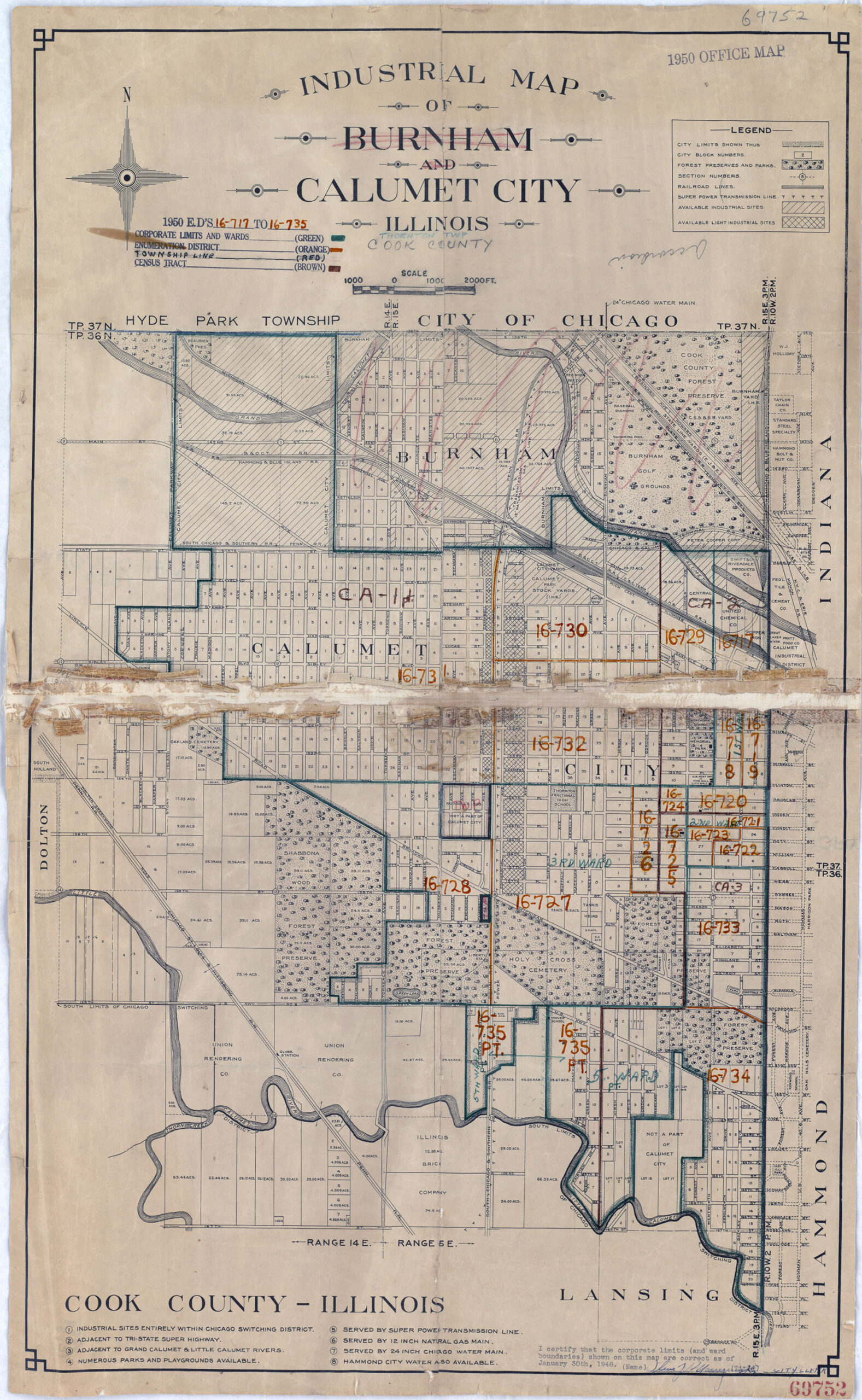

The traces of his life in Branson are more muted. There’s a development in suburban North Branson called Neihardt Heights, which bears as much relationship to the man himself as any suburban development does to its eponymous weeping willows or hidden springs. However, with the help of my colleague, College of the Ozarks librarian Gwen Simmons, I was able to locate the site of the former Neihardt home, which was demolished in the 1980s, a Chinese restaurant put in its place. In 1989, the Branson Arts Council installed a monument: a modest boulder adorned with a bronze plaque. Today that monument sits, overtaken by Virginia creeper, just blocks from the excesses of the Strip on the corner between the Koi Garden Plaza strip mall and the Branson Visitors Center.

Branson isn’t much of a town for poets, of course, and even if it were, contemporary neglect of Neihardt’s poetry is probably justified. He wrote Orientalist lyric poetry based on Hindu mysticism and self-conscious imitations of European epic poems, complete with epic similes, but about the American West. Much of his work is in rhyming couplets in an excessively regular iambic pentameter — hallmarks of a poet lacking technical sophistication. And unlike even other quasi-European poets like Longfellow, Neihardt shows little ability for a memorable image or turn of phrase. Unlike his fellow Nebraska writer, the better-known Willa Cather, Neihardt’s poetry looks primarily to European creative models. Cather’s greater artistic accomplishment is that she created a distinctively American literary form, rather than imposing European models on a place that has its own life and culture.

Neihardt is justly remembered, then, less for his poetry than as the transmitter of Black Elk’s ideals: a vision of “the sacred hoop” uniting all creation in a holy order. And here Neihardt comes into his own. Even as he drew primarily upon the classical epic for his poetic form, he evinced an interest in an indigenous American social vision that Cather couldn’t match, one in which the first peoples of this land have an equal voice with those of us descended from settlers. For all the justifiable controversy around the authenticity of Black Elk Speaks, it’s undeniable that Neihardt sought a vision for the Midwest that had more to do with cross-cultural peace than settler violence.

I suppose one could see the conjunction of the Koi Garden Plaza and the Branson Visitors Center as a kind of crass instance of that cross-cultural wholeness. But I’m more inclined to contrast Black Elk’s vision with the ideals represented by the Branson Strip. However multicultural the Strip might come to be, consumer capitalism has little to do with the Sacred Hoop.

Like Neihardt, I’m a Nebraskan expat living in Branson. When I can’t avoid the Strip, I confess that I’m prone to contempt, to contrasting it with the vision of wholeness I sought in books like Black Elk Speaks. But I recall, too, that part of Neihardt’s interest in Black Elk arose from his Orientalism, and so I’m forced to acknowledge that Branson’s exploitative tendencies also reflect a side of Neihardt.

Neihardt has always represented a vision of what we could be, for good and ill; if that vision diverges from what we in fact are, it does not do so completely. Nor ought we to scorn such visions when they fail, as they must, to live up to what is best in us. Yes, settler visions of what could be gave us the Branson strip and Manifest Destiny. But it will only be through visions like Black Elk’s sacred hoop that we might found a Midwest that corresponds with the best in Black Elk’s, and in Neihardt’s, hopes.

Matt Miller, a native Nebraskan, now lives in Branson, where he serves as Associate Professor of English at College of the Ozarks. His first book, a collection of essays titled Leaves of Healing, was published by Belle Point Press in late 2024. Find him online at matt-miller.org.