The story of Asian carp is the story of political contest, unintended consequences and a nascent-at-best understanding of the intricate relationship between any one species and its broader ecological context. In Overrun: Dispatches from the Asian Carp Crisis, environmental journalist Andrew Reeves tangles with this evolving challenge.

Anyone who spends time on the waters of the Mississippi River basin is likely familiar with Asian carp through both experience and lore. Regarded as one of America’s most voracious invasive species, Asian carp in North America (including the grass, silver, bighead and black carp) average around 40 pounds and are notoriously capable of causing serious injury to recreationists as they jump from the water. They have grown so prolific that, at the turn of the 21st century, researchers estimated bighead carp comprised 97 percent of the Mississippi River’s biomass.

Reeves situates Asian carp in a wider, incredibly complex web of interspecies entanglements, beginning by discussing optimism in the mid-20th century that grass carp could save waterways from yet another notorious aquatic invasive species, the federally listed noxious weed hydrilla. He proceeds with staggering, at times almost excessive detail through decades of changing land use and regulations and increasing public anxiety about the species’ demonstrated ability to overwhelm watersheds. Reeves ends with an outlook on what the future of Asian carp, and implicitly the environment writ large, holds in the era of Donald Trump, referred to by one of Reeves’s informants as the “Asian carp of politics.”

Reeves presents the crisis chronologically and geographically, with fieldwork done throughout the fish’s invasion pathway from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast. The scope of the carp’s reach is astounding, as is the scope of the story Reeves presents. Reeves’ interest in Asian carp was spawned during his energy and environment reporting for the Toronto Star. In 2012 he read of an $18 billion plan by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to separate the Great Lakes from the Mississippi River watershed by cutting off the aquatic links between the two water bodies in Chicago and effectively reversing the engineering of the upper Mississippi a century ago. Reeves noted the increasingly politicized public discourse surrounding Asian carp at this time typically collapsed into two simplistic narratives: Either reckless aquaculturalists in the South or the historic flood events of the early 1990s, which supposedly amplified the crisis by sweeping the species into previously uninfested areas, were to blame.

To nuance these narratives, Reeves combs records and interviews “some eight dozen” people connected to the crisis. He discusses paradigmatic schisms in natural resource management and the political valuing of environmental versus industry interests. He visits with aquaculturalists who detail the process for how to produce carp incapable of breeding and the regulatory context that demands this. Regarding the notoriously stringent Lacey Act, one carp producer remarks “You’re better off trafficking in cocaine than to move any fish — not just Asian carp, but any fish — across state lines illegally.” Reeves dives deep into the geologic history of the continent and the bone structure of the bighead carp to recognize a simple but profound truth: “Everything in this world is more superconnected than we could ever possibly imagine.”

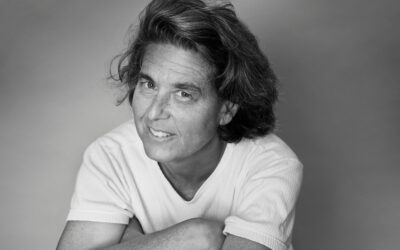

Reeves shows the readers how to appreciate the staggering weight of this ongoing crisis and the extent to which it is entrenched in economic globalization, shifting values about environmental management and the practical questions of resource allocation. There is no shortage of moments while reading where it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the complexity of the issue, the number of players — both human and non — and the absence of easy answers. This feeling does not give way to defeat largely because of Reeves’s voice throughout the text, which retains a quality of optimism and genuine fascination. The text is equal parts travel memoir and investigative journalism. The more personal narrative that runs throughout the book offers reprieve from what can at times feel like a too-frenetic accumulation of detail. Reeves writes honestly about the extent to which this work demanded a shift in his own approach to environmental issues and this sort of companionship is comforting for the reader.

Ultimately, the story that Reeves tells is about the precarity of ecological equilibrium. It is about the stakes of rapid environmental change and new vulnerabilities that span across species. Coming to terms with this requires qualitatively new thinking. Regarding the situation’s complexity, Reeves paraphrases Harvard botanist Peter Del Tredici: It’s strange to think of Asian carp “in so binary a way as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ — they are us.”