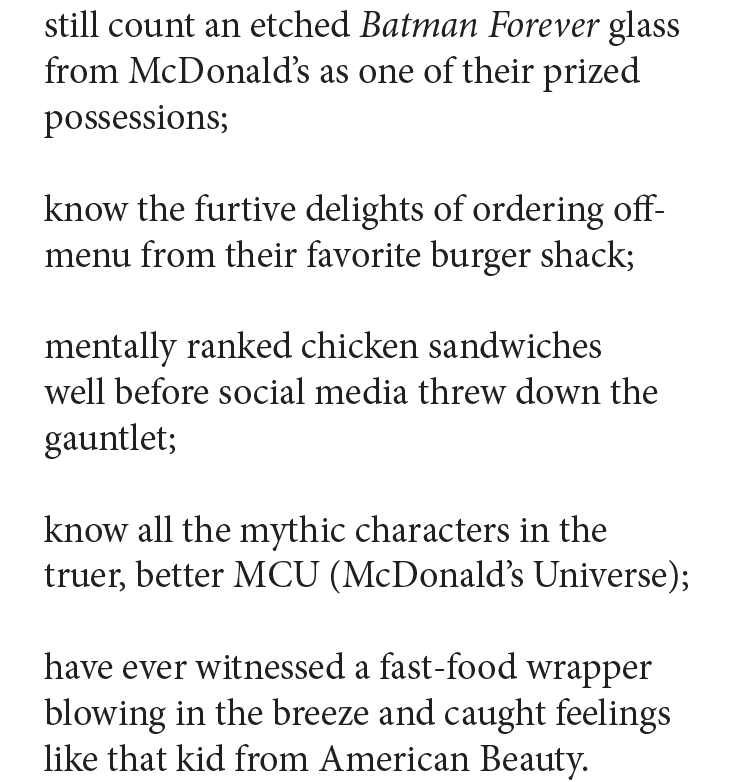

With El Dorado Freddy’s, Danny Caine and Tara Wray deliver art for people who:

Caine’s wry, deceptively compassionate poetry pairs perfectly with Wray’s photographic witness to consider what fast-food culture means to America — what it has to say about us and to us. In their introduction, the pair discuss how one’s work complements and completes the other.

“The commercial landscape that interests us is equal parts linguistic and visual, full of hyperbolic slogans, optimistic menus, neon lights and saturated colors,” they write. “Any meditation on what it means to be a chain restaurant consumer must be based in both language and image.”

Caine’s poems, almost exclusively named after food franchises, share a spirit with the best work of David Foster Wallace. Like Infinite Jest, El Dorado Freddy’s never shrugs off or salutes a highly-mediated, consumerist culture. Instead, the Lawrence, Kansas-based writer and owner of the popular Raven Book Store recognizes a more complicated dynamic. Nostalgia, satisfaction, revulsion and the slipperiness of memory are more than bonus fries at the bottom of Caine’s grease-stained paper sack; they are why these poems exist.

He connects the dots between generations of Americans while also uniting generations of his own family. Through the of El Dorado Freddy’s, he documents his partner’s pregnancy; ultimately, he creates a collection that serves as a loving letter to their then-unborn child. Dispatches from corner booths and crowded buffets do the work of family photo albums and offer a chance to impart the beginnings of wisdom.

Caine recalibrates the reader’s perspective from his opening poem. Whether the chicken or the egg came first is an outmoded question and unworthy of our time; using the “see also” language of a technical document, he casts the chicken nugget as the catalyst for so much of our modern customs and online behavior. In breathless, run-on verse, he traces the value-meal item’s invention by a Cornell food scientist through history to its inclusion in the “great American food” that President Trump served the national champion Clemson University football team.

“See also the most retweeted tweet of 2017 was / a teen named @carterwjm asking Wendy’s how many retweets it would / take for a year of free chicken nuggets see also it was retweeted 3.6 million / times and it successfully earned young Carter free nuggets for a year,” Caine concludes, leaving the period off his last line, as if to say these nuggets keep moving, like a constant current, through our lives.

Caine also chronicles moments of beauty punctuated by inevitable vulgarity. “Tonight is calmer: quiet zydeco burbles / punctured by a manager who aced the training session about shouting,” he writes in “Popeye’s Louisiana Kitchen.”

In the same poem, he cleverly invents a class of eaters: the “strict chicken tendertarian.” So much of Caine’s work puzzles over ways fast food marks the identities we assume or passively accept. In “In-N-Out Burger,” he differentiates between people who would order “animal style,” “baby style,” “Martha style” and “California Style.”

A “Culver’s” stop prompts a question about regional speech patterns: “I hear / a cashier say all our burgers are Butterburgers, so. / Is that a Midwest thing? The trailing so?”

In “Panera,” Caine takes on the persona of a millennial who is hipper- and healthier-than-thou. “Panera you’re our sword. / We hoist you to behead Applebee’s / Cheesecake Factory, and B-Dubs too,” he writes.

Elsewhere, Caine encapsulates specific brand experiences so lyrically that scales fall from your eyes and it feels like you’re the place for the first time. “Cracker Barrel,” for example, isn’t “home but the place that tries so hard to feel like it.” In turn, at Texas Roadhouse, “the food tastes like / this is Cracker Barrel’s little brother / who drinks too much and sleeps too late.” And in “Applebee’s” Caine writes, “This is only / a neighborhood bar and grill / if the neighborhood is a hotel lobby / in 2003.”

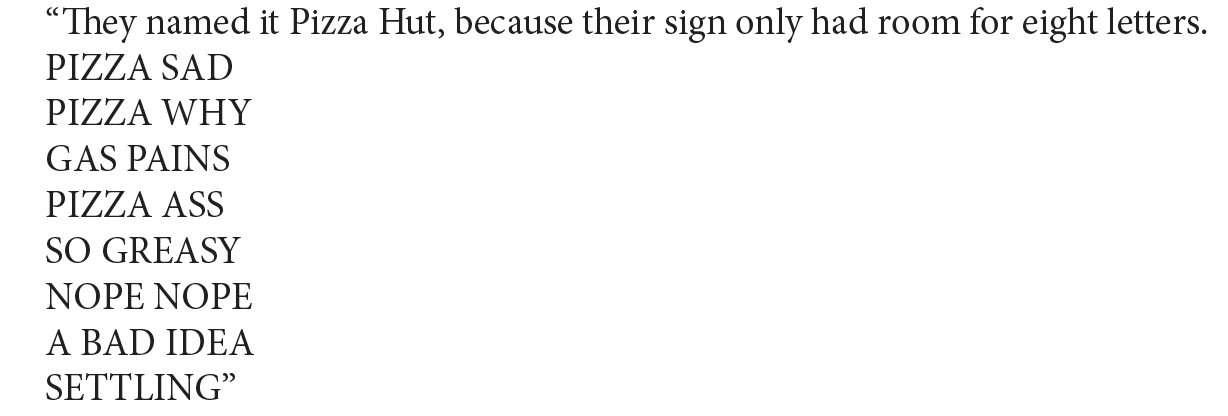

As any poet worth their salt, Caine toys with the particularities of the English language to find their fulfillment, landing a wonderful punchline in “Pizza Hut: Our Story”:

The word-meals that stick to the soul arrive in Caine’s direct addresses to his child. At “Cici’s Pizza,” he transmits fatherly musings and restates the central question of the book: “The thing about nostalgia is / maybe it doesn’t work / if the thing wasn’t fun / to begin with.”

The book’s closing poem, “Krispy Kreme,” reads like a segment of Biblical wisdom literature. Proverbs calls on parents to “train up a child in the way he should go,” promising “even when he is old he will not depart from it.” If this poem lands, Caine’s child will never depart from the how, where and elusive why of getting your order right. “Finally, if you see / the Krispy Kreme sign / lit up, you must go. / I don’t know how to make / magic but I know where / you can go to find it,” he writes.

Serving as a visual intermission, yet binding the book together, Wray’s photographs bisect the text; the Kansas-born, Vermont-based artist possesses a keen eye for the strange, glorious geometries of a fast-food nation. Her images — all taken in Kansas or Missouri — look out from inside a restaurant window, the reverse image of a hand-painted cheeseburger obscuring the landscape; or portray a row of pizzas, lined up at a buffet, as an entrancing series of cheese-covered mandalas. Rain blurs the sight of a Kansas Pizza Hut, making it as poetic as anything Caine pens. Even the reflection of a Waffle House in the window of a KFC becomes sharp and meta cultural commentary through Wray’s lens. She portrays food and beverage as desert oases — and captures them at their least appetizing. The cover image, donut detritus spread across parking-lot asphalt, speaks to the sweetness and disposability of our relationship with food made for the masses.

Caine and Wray present chain-restaurant culture as one of the true all-American art forms, as human, flawed and intoxicating as baseball or jazz. Focusing on distinctly Midwestern expressions, they question what it means that this food both cheers and clogs the heart of our country. On every page, the answer comes back: everything — humor and heartburn, Potato Oles and loose-meat sandwiches, rites of passage and fresh responsibilities — should be enjoyed in moderation.