At the newspaper where I worked in college, we were taught that a story’s lead was a story’s everything—This. Happened. The lead was the whole and the start, an incision through which a writer’s needle and thread might penetrate, stringing along all the details to follow: the characters, the quotations, the decisive, uniform facts.

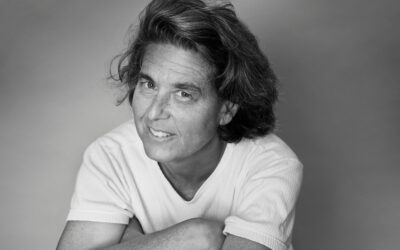

Vanishing Monuments, the debut novel by Canadian/Kansas City writer John Elizabeth Stintzi, bears the imagery of this form. But in the case of their story, the thread hangs in a darkroom of the mind, and the details strung along its length are less the facts of reportage and more the dripping enlargements of ever-developing photographs. For Alani Baum, the non-binary photographer and narrator of the novel, these murky and blended frames make up their life’s journey, a maelstrom of escape and rumination that, despite Alani’s serious efforts, remains ill-defined, ever open to interpretation. This pain becomes a catalyst for great personal metamorphoses in Alani, and a powerful force that moves readers through a novel that Stintzi frames, reframes, and frames again.

After running away from home and life with their mother almost thirty years ago, we meet Alani Baum at a point of relative stability. A successful artistic career, a professorship, long-standing relationships, the works. When news of their mother’s accelerated dementia arrives, though, Alani is spirited from the world they’ve created in Minneapolis and back to the life from which they fled as teenager. Now, in Winnipeg MB, Canada, the novel straddles a fraught history: the to-do list of obligations the child must contend with on behalf of their aging parent, the haunted world of their shared past, its abandonment, and the ways in which all these elements touch and alter the other. Further, Alani must contend with their own sense of plurality, the membrane through which everything past and present filters—every sigh, every act of love or neglect.

As readers will learn, perhaps the narrator we’ve met is more rightly named Sofia. Or Al, as Alani later identifies themselves. Or simply, “the girl who runs away,” the girl who threatens to come back into Alani’s bones and “take over, like a surfer on a wave of fear.”

their identity is an ascension to middle space in their interior life

Whether they’re wearing a packer and jeans, or a sun dress, it seems readers have met all and none of these people. Alani navigates the worlds they leave behind and the ones they create, introducing and reintroducing themselves in a variety of forms and names, never exclusively one or the other. For Alani, the multiplicity is the point, and represents a hard-won balancing act in a life spent striving toward truth of identity. Like the story of Icarus that Alani carries around Winnipeg, their identity is an ascension to middle space in their interior life, a space threatened always by rising too far and burning up, or by submerging so low as to lose any sense of the self.

Even that relative stability Alani has achieved by the start of the novel can become a strange and alienating thing—the discovery that they’ve begun to show up on time, dutifully fulfilling obligations to the erasure of other, less punctual aspects of the self still writhing within.

“I’d figured out how to appear ordered, found a way to make my body become a thing I could hide in again,” Alani says. “I was stowed away. Exiled.”

This sense of exile is manifold, at times self-imposed, and emerges from within as much as without. Alani’s first, and most important, escape was from their mother, out of their city and a situation that threatened to sink them both. Later in a new life, Alani would flee again, this time to Hamburg, Germany, a setting which provides another of the novel’s well-woven plot lines. Time moves forward, exiling everyone from the people they used to be, and in an effort to bar against these effects, Alani constructs an elaborate “memory palace.” It is a mnemonic structure, based on their childhood home, and so tangibly imagined and intentionally populated as to be almost indistinguishable from the book’s physical landscape. Indeed, readers will spend a good portion of the novel here, walking its halls with Alani as they examine the memories they’ve hung on the walls, or buried in the back room. Winnipeg itself is often a lively, well-described beast, but it is this palace, both of memory and hard, physical reality, that steals the show. This duality of setting becomes a charged and ethereal center for the narrative, structuring and mirroring the many recurring plot threads and timelines—just as it does for Alani.

For readers, the device provides the imaginative space necessary to fully inhabit Alani’s life, focalizing and framing their story’s ever-developing snapshots, and allowing the time and environment for them to clarify in the darkrooms of our minds. In this, Vanishing Monuments presents a compelling and suspended kind of portrait, a space in which multiplicity of truth can coexist, can even contradict, and still be, at its core, the truth.