That sweaty night the Conservatory was full of young punk rockers, as it usually was, whose intentions were to get too drunk to care about the sound quality or even the performances. The wretched but beloved dump of a venue in Oklahoma City always smelled like old drinks full of older cigarette butts, every surface gleaming with some degree of stickiness, and the bathrooms were coated with stickers, stench, and brokenness. Certainly, none of us in the audience that night were prepared for what an unknown, unimposing opening act from far-flung Missouri would bring us.

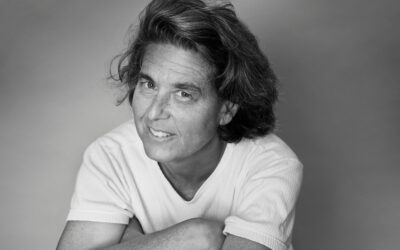

After some locals opened with a set perhaps too soft for the likes of that night’s crowd, two strange men took to the tiny stage, a platform rising maybe only a foot from the floor and only slightly larger than most people’s dinner tables. It was almost completely devoid of equipment when the men, who called themselves The Hooten Hallers, began to set up. While Andy began assembling a drum kit, John began to pace, wringing his hands, and grinning weirdly. The look on his bearded, sweaty face was wild, hurried, and almost nervous. He moved around the tiny stage like a panther in a sideshow cage.

Finally, Andy gave John a nod. Someone slipped a guitar into this strange beast’s hands, and everything about John changed. With the addition of his instrument he was complete. His entire being relaxed, and his eyes swept over the crowd with an unnerving look of total confidence.

A hard, dirty blues riff unwound itself into the air and a mean, pulsing rhythm beat forth from the kick drum. John swayed in his Carhartt overalls, his head cocked back and to the side, his eyes closed. When the lyrics came they were the mournful roadhouse lyrics of a man who has truly known blues in his life.

His voice isn’t so much gravelly—it’s more like broken glass. There are times that John’s voice finds a real Tom Waits quality in its deepness and grit, but sometimes it’s more like Screamin’ Jay Hawkins in its ascending-pitched growls of lyrics. But maybe it’s more accurate to say that John’s vocal cords are the conduits by which the ghosts of John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters or Howlin’ Wolf communicate. When The Hooten Hallers perform “Tonite, He’s on Death Row,” John appears to weep the lyrics and bleed the notes onto the neck of his guitar.

That night they played all the songs from their album Greetings from Welp City! Immediately obsessed, I bought the CD and wore it out waiting for another release.

Chillicothe Fireball came out in 2014, introducing Kellie Everett on bass and baritone saxophones. The Midwestern-blues sound had evolved into something else, emanating a sense of swampland magic as sorrowful and alluring as a French Quarter funeral. It’s mournfully aggressive, the kind of music you want blaring from your car when you step out to do the most badass thing you’re ever going to have to do.

The Hooten Hallers have channeled the songs of all the heartache and anger and triumph that anyone living on the fringes has come to know. I shiver when I hear “I Know Everything” or “I’m Used to the Truth,” with the beautiful instrumental work and simple-yet-profound lyrics like, “I’m stronger than dirt and I ain’t in no hurry. I’m used to the truth, I’m from Missouri.”

So the band is in no hurry, but something new is being painstakingly crafted somewhere as I write this. An acoustic EP is due out this summer, and rumor has it a full-length album will follow in 2017. From what I’ve seen around YouTube I get a sense that the band’s acoustic sound will bear the influence of some wonderful, dead country outlaws, but I don’t think the Hallers could completely depart from the blues even if they’d want to.

So whenever the new music comes, I’ll be waiting for it, and I hope it’s dirty…that’s the truth.