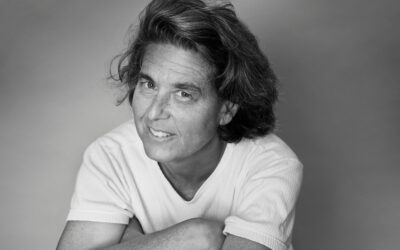

Most journalists and political scientists lose sleep trying to define Midwestern ideology. Not Julianne Couch. In her book The Small-Town Midwest, the author presents the 46.2 million people living between the Rocky Mountains and the Mississippi River as anything but a monolith by going directly to the source. Her personal encounters and conversations the notion that the Midwestern subject must only be broached during election years or after natural disasters, and they foretell a future shaped by strong leaders.

A Kansas City native who’s spent most of her adult life living in small towns, Couch’s roots wrap tightly around her narrative. She details nine Midwestern towns in this book not as an academic, but as an “interested traveler,” an approach that fosters the book’s weaknesses. Couch begins necessary conversations about justice, sustainability and economic vitality in the Midwest, but, like a traveler with too many stops on her journey, she doesn’t dive deeply into any issue in particular.

In each town, Couch explores community, and what makes a good one: meaningful work, multigenerational friendships, safe neighborhoods, frequent family-friendly gatherings, local lore and deep connections to nature. These are the qualities large, disjointed cities often lack and the ones intimate Midwestern communities often offer.

But these small towns also have their downfalls. Inadequate housing, job loss, healthcare inaccessibility, aging demographics and a lack of educational opportunities are all qualities that Couch says make small-town life in Middle America unappealing and, at times, impossible. She addresses racism, economic dilapidation, the privatization of land, and industrial agriculture, but only hovers over the issues without addressing their real roots and ramifications.

For example, Couch attempts to describe the racial landscape of Missouri in the chapter on New Madrid, a town with an African-American population slightly above the national average. But her commentary on race falls short, failing to further explore the aftershocks of Ferguson or the statewide racial tensions that led up to the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown and the civil unrest that followed. She does briefly discuss Jim Crow-era segregation with a local African-American woman working in community development for a nearby town, but Couch quickly moves on to discuss the area’s job market. Why didn’t she ask about the relationships between residents and the police, about kids and drug use, about access to healthcare in a state with a Republican majority hellbent on cutting Medicaid?

By focusing only on the small-town leaders engaged in community development, she misses an opportunity to discuss Midwestern culture in some of its ugliest forms. Apathy, disconnect, lack of education—these are real issues plaguing Midwestern communities. Some of the states in this region rank among the lowest in voter turnout. But Couch seems to be uninterested in writing about Midwesterners who aren’t involved, and that is her biggest shortcoming in this book.

Yes, the work of small-town leaders deserves to be written about. But perhaps a more fruitful discussion would involve an intentional balance between their stories, the stories of people less involved in their communities, and deeper commentaries on the policies that make revitalization difficult.

However, Couch’s book is a revitalization effort in itself. She writes to look forward, to focus on the good that’s coming for the region. She excitedly notes that young people might be starting to think it’s cool to live in the Midwest. “Like other forms of life, communities have a cycle and transition naturally from hopeful beginning, to thriving, to struggling, to ending their days as vessels for nostalgia and reflection, but also for rebirth,” says Couch. By attempting to document this cycle, however incompletely, Couch is also working to help the region thrive.