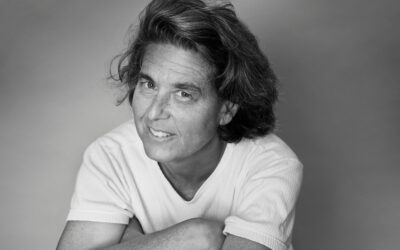

In Bad Faith, Theodore Wheeler’s debut collection of short stories, it is certainty that causes trouble. Ideas become boundaries, lines any reasonable person might draw for him or herself: beliefs in who they are or were, that what they’re doing is the best thing for them. Marriages, homes, children, careers. And yet here, at the borders of identity and place, is where Wheeler makes his incision.

The collection opens with “The Mercy Killing of Harry Kleinhardt,” a window into the smoldering world of Aaron Kleinhardt. He has returned home to fictional Jackson County,

Nebraska, to care for his dying father Harry, who’s going through chemotherapy. He is back to a home where the “transgenerational losers” at the motel bar know Aaron the way people of Jackson know anyone: by “whose daddy owned what, whose uncle worked where, whose granddaddy died fighting who. These people knew Aaron because they knew his father.”

So they thought. And so we might think. As an opener, “Mercy Killing” is all latent energy and misdirection. What’s at stake for whom isn’t quite clear. Aaron is introduced as a roving ladykiller, a scrawny, tramping runaway whose choice line of pick-up is a snapshot with his trusty digital camera and a compliment. He knows it’s cheap, and he knows it works. When a local tells Aaron his presence is a good thing for his father, he responds, “It’s an errand.” And yet Aaron isn’t sure whether that father even wants him there. Together on the page, Harry and Aaron operate like discordant conversations vying for the room’s air—two people talking about different things, stopping short, holding silent, getting nowhere. At one point while Aaron cooks breakfast, Harry tells him he should leave, vaguely addressing his impending death.

“‘You should go,’ Harry repeated. ‘This…’ he swept a shaking hand over the table. ‘This is happening whether you’re here or not.’”

Aaron sets the eggs on toast.

His father grabs a napkin and says, “Are we going to eat or what?”

Aaron’s story becomes a kind of Rosetta Stone to Bad Faith. It is a wink at what’s in store in the following seven stories and vignettes: tales populated with grungy barrooms and interstate fill stations, life in the city versus life outside its confines, pensive and opaque men looming in the memories of their children.

Wheeler, a graduate of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and Creighton University, lives in Omaha. He knows the land, the state, and he inhabits these settings and imbues them with an aromatic sense of familiarity. Even places as foreign as Central America carry Wheeler’s eye for detail and authenticity: “tuk tuk” motors, the number of blocks between the Kellogg Rooming House and the train depot, the formaldehyde smell of a village church that hosts the “visitation and the funeral and the reception after the burial,” the necessity of late-night runs to the city because small town pharmacies have already closed.

Often in the stories of Bad Faith, it is as if the narratives are started and resolved by the land itself. In “Impertinent, Triumphant,” a husband returns late from a vacation in Atlanta to find his artist wife—whom he resents, of whom he’s jealous—waiting for him at the Nebraskan airfield. “We bounced onto the bench seat and swung out on the highway to reach full speed, the windows down all the way, seatbelts flapping loud in the gale, tires gripping over the patched pavement. We smiled out over the land. Jacq looked different in Alliance, on our ranch, than she did in any city.” To Wheeler, we are made of the places we live and grow. Our stories emerge from that context, from travel and leaving and, ultimately, our return.

Wheeler’s characters bend and stretch their conceptions of self to fit these places and situations, dipping their feet in the often boiling waters of possibility: seductions, switching careers against their own nature, hopping the night freight through Nebraska’s Sand Hills. And that elasticity is mirrored and conferred by Wheeler’s prose, his ability to pick up on the

stark voices of his characters and the drama of their worlds. In “The Missing,” a man named Steve leaves for a spontaneous trip to San Salvador against the wishes of his six-months-pregnant wife. The story is told in a keen series of direct, staccato sentences that form the current in which Steve is caught. “Worthy told Steve to come visit San Sal for a few days. Why San Sal? Because I live in San Sal, Worthy told him.”

The largest tonal departure of the group comes in “The Current State of the Universe,” which broaches a region of comic, speculative fiction told in the voice of a man training “you” for a job at Make Things Right, a karmic-retribution company. In essence: “It’s simple. You cut someone off in traffic, flip them the bird, and in the morning the gate is open and your dog has run away. It isn’t a coincidence. It’s us. We’re the Furies of the modern world—the vengeance of a god gone corporate.”

This is a character who knows himself, accepts himself, and as such makes the story even more of a departure from the rest of Bad Faith, which carries a perpetual sense of transience in its characters’ identities and their truths. Shifts of self and metamorphoses are the norm and range in consequence: sometimes harmless and sometimes catastrophic, always teasing the reader along.

It is Aaron Kleinhardt, Wheeler’s most enigmatic creation, who comes to represent this range in the collection as a whole. Formally, Bad Faith is bookended with Aaron. He gets the subdued opening story, in which we’re shown his politics, scars, his childhood dreams that his absent mother might swoop in and rescue him away from Nebraska. And he’s a main player in the sudden, thrilling end-story. He represents the book at its slowest and most ambiguous, and he is Bad Faith at its darkest and most challenging. That pick-up of his, taking women’s photos as an inroad to their apartments, oozes between the cracks of the other stories, pointing our gaze to the women’s “porcine legs” and midriffs, the way their jeans fit and whether they might’ve been pretty in high school.

Seven vignettes punctuate each of the eight longer stories, describing in a few paragraphs the first encounters between Aaron and his successful flings. As a collective, they were published in literary magazine Fogged Clarity as “Kleinhardt’s Women.” Separated across Bad Faith, the anecdotes at first offer pitiful and confronting palette cleansers to the other tales. Further along, they take on larger consequence, creating an ominous continuum between Aaron and the characters and settings of Wheeler’s other stories.

In one life, a woman who sings the blues alone in her apartment is a mere annoyance to her neighbor, and in another life that woman is to Aaron the target of desire and ultimately hideous and violent urges.

The effect is a sense of thematic and conflictual cohesion that, by the book’s finale, feels like the narrative fabric of a novel. It is certainly as satisfying.

In these 200 pages, in Nebraska and the rural Midwest of Wheeler’s creation, deception reigns and faith in anything can quickly turn ill. In urges both petty and enormous, his characters move through their lives confused or falsely certain—searching at best. Often, as the book’s cover might suggest, they are the wolves in sheep’s clothing of their own undoing. They are spurred by secret passions and earnest lies, discovering the weakness and hope that was there all along.