When the android singer Cindi Mayweather first appears onstage, she brings an ecstatic crowd to its feet with a fast-paced dance number that doubles as a warning: She and the rest of us are trapped.

“We’re dancing free, but we’re stuck here underground,” she intones, sharply dressed in black and white, her prominent pompadour knocked loose by her crackling, spirited dance moves. She performs during an auction as the city of Metropolis’ rich and powerful bid on the identical androids strutting along the catwalk below her. It seems clear the bidders are the ones keeping her underground, but Cindi sings right to their faces: “All we ever wanted to say / Was chased, erased and then thrown away / And day to day we live in a daze.” Her fellow androids look up at her and sing backup: “Revolutionize your lives and find a way out.”

Cindi sings with such vigor that she rises into the air as the song slows to a dreamy coda. She then collapses back to the floor, motionless as her fellow androids solemnly surround her and bear her away.

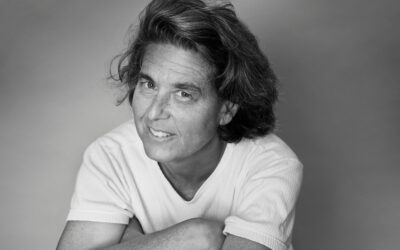

More than a decade later, Janelle Monáe, the 33-year-old singer and actor who performed as her alter-ego Cindi through one EP and two full-length concept albums, has revolutionized her life and broken out from underground with 2018’s Dirty Computer. Nominated for Grammy Awards album of the year, the funk/R&B/hip hop collection and its accompanying short film of the same name display Monáe at the most vivid, forceful and personal we’ve yet seen. (Golden Hour by Kacey Musgraves won the honor.)

Many reviewers see the album as a new page for Monáe and a shuffling-off of Cindi’s mechanical coil — “Janelle Monáe Strips the Hardware for Humanity,” as one NPR review put it. It’s true that Dirty Computer reaches new territory, doing some things for the first time among Monáe’s albums and doing other things more or better. But I’ve come to think of it as simply a next step in the political, personal, science-fiction-infused journey Monáe has shared with us all along.

Monáe grew up in a large extended family and a working-class, heavily black area of Kansas City, Kansas. Her mother worked as a janitor, her stepfather as a postal worker, and her father was mostly out of the picture until he overcame drug addiction, Monáe has told The New York Times and other outlets. She sang Lauryn Hill on repeat and dove into musical theater as a kid before leaving as a young adult for New York City, then Atlanta. There in 2007 she released the EP Metropolis; its handful of songs included “Many Moons,” the anthem whose music video features the android auction and ascension.

Metropolis set several patterns that would hold in Monáe’s work from then on. It introduced the world to Cindi, a savior-like figure from the future who goes on the run from the authorities after falling in love with a human. It established Monáe’s favored sci-fi setting, where androids were stand-ins for people who aren’t white, people who aren’t straight, the marginalized of all stripes.

The video to “Many Moons” ends with a quotation attributed to Cindi, “I imagined many moons in the sky lighting the way to freedom,” that recalls the Underground Railroad (part of which went through Monáe’s Kansas City community) and civil rights leaders.

Finally, Metropolis showed the proper response to many of Monáe’s songs is to just let loose and dance. Dancing and dreaming and acting a fool, she says repeatedly, are subversive and powerful acts in the face of repression.

Cindi’s saga continues through Monáe’s next two albums, 2010’s The ArchAndroid and 2013’s The Electric Lady. Monáe shines in multiple genres at once, running from the heart-pounding battle cry “Cold War” in ArchAndroid, for example, to the same album’s Simon & Garfunkel-esque “57821.” The funky beats of “Q.U.E.E.N.” and “Givin Em What They Love,” a Prince collaboration, follow in Electric Lady. Orchestral and spoken-word interludes arranged by Roman GianArthur and others weave both works together and echo the structure of 1998’s hip hop classic The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill. Monáe also stretches her capable voice from cooing choruses to primal screams and languid electronic distortion. Through it all, she sings of Cindi’s search for love, sisterhood and freedom.

I think of this pair of albums as something like a wave function in quantum physics, which sees atoms and elementary particles less like hard little balls and more like clusters of all of the possible locations and ways they could be at once. A particle collapses from that cloud of probability into a firmer, single reality when it’s observed in some way. Something similar seems to happen throughout Monáe’s discography.

ArchAndroid is the most eclectic, including psychedelic “Sir Greendown” and “Mushrooms & Roses,” the snapping “Tightrope” and the operatic, almost nine-minute “BaBopBye Ya.” Cindi’s story moves backward and forward in time, unconcerned with strict plot coherence. The album can also seem fuzzy at times as a result, and the second half can’t keep the pace set by “Tightrope.”

Electric Lady brings more concentration and explicit connection to real-world events. Cindi’s story is at its most straightforward: The album is presented as a radio show on a Metropolis station defiantly broadcasting Cindi’s stuff despite the bounty on her head. It references Monáe’s upbringing in Kansas City multiple times. Most notable is “Ghetto Woman,” a kinetic, percussive tribute to her mother, grandmother and other working-class black women who work long, exhausting hours and are “the reason I believe in me.”

Dirty Computer brings all of this background to a singular, masterful point.

The album and short film — or emotion picture, as Monáe calls it — center around the character Jane 57821. Jane and others are “dirty computers,” humans whose thoughts are deemed wrong, radical, unclean by a quasi-religious, mostly white authority. Instead of androids, dirty computers are more like replicants, the living but artificial humans hunted down in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (a comparison the short film leans into with its synthesizer-heavy introduction and ritualized call and response used to analyze Jane’s brain after her capture). Technicians rummage around her memories and dreams — the album’s featured songs — to erase them.

What follows in the album and film is a genuinely personal voyage for Monáe, much like Beyoncé’s 2016 Lemonade that chronicled her grappling with her husband’s betrayals. Monáe begins by simply living her life, “young, black, wild and free,” and wanting to stay that way in “Crazy, Classic, Life.” “I am not America’s nightmare / I am the American dream,” she croons. A man whose voice sounds remarkably like Martin Luther King Jr.’s quotes the Declaration of Independence’s guarantee of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness to solidify the tone.

But she knows something is wrong. By the end of the song, she’s rapping about how she and a non-black friend who make the same mistakes and break the same rules nonetheless see their lives swing in completely different directions.

Monáe reacts to this injustice first with nihilism, imploring someone to “make love till we’re numb” in the seductive “Take A Byte.” She doesn’t care how screwed we all are, she and Zoë Kravitz proclaim in the jaunty “Screwed,” which delivers one of my favorite lines in the album: “You fucked the world up now / We’ll fuck it all back down.”

Within this supposed indifference are the seeds of political and personal anger, of romantic love and sex, of pride. They bloom in the rapped, confrontational “Django Jane,” the coy and playful “Pynk” and the Prince homage “Make Me Feel.” The short film around this time shows Jane’s memories of falling for another woman, appropriately named Zen, who’s portrayed by Tessa Thompson and also gets captured.

Then comes the fear of letting all of these emotions grow and becoming vulnerable, and the album’s pace relaxes to soak it in. In “So Afraid,” Monáe belts out, “What if I lose? / Is what I think to myself / I’m fine in my shell / I’m afraid of it all, afraid of loving you.” But she doesn’t give up, redoubling on love and its power and lessons. “Even when you’re upset, use words of love, ‘cause God is love, Allah is love, Jehovah is love,” Stevie Wonder counsels her in the spoken track “Stevie’s Dream.”

Monáe emerges triumphant and euphoric in the hand-clapping final track, “Americans,” just as Jane gets through to Zen and they escape together. She belongs here, Monáe sings, even with the country’s history of sexism and homophobia and of seeing “my color before my vision.”

Monáe emerges triumphant and euphoric in the hand-clapping final track, “Americans,” just as Jane gets through to Zen and they escape together. She belongs here, Monáe sings, even with the country’s history of sexism and homophobia and of seeing “my color before my vision.” The speaking man returns to tell an audience this is not his America until Latinas and Latinos don’t have to run from walls, until same-gender-loving people can be who they are, until all have a chance at success in life — and it will be his America in the end. Dirty Computer writes a new social contract for America and asks in its final line, “Please sign your name on the dotted line.”

Monáe here is a woman we haven’t seen in earlier albums, one full of agency and no time for asking, “Is that OK?” as she does in both ArchAndroid and Electric Lady. The album has understandably drawn a lot of attention as Monáe’s first embrace of her wide-ranging sexuality. Her canned response that she only dates androids (a callback to Sun Ra, the avant-garde jazz musician who insisted he was an interplanetary voyager) is no more.

Monáe here is angry and political and rough-edged, dropping F-bombs and the N-word and making thinly veiled references to President Donald Trump as the devil. She’s also focused — the album clocks in 20 minutes shorter than its predecessors and lacks their dragging final acts. Lyrically speaking, it’s remarkably self-contained, featuring American-ness and dreams among several bookend themes that come in near the beginning and resolve or expand by the end.

The Monáe here, in other words, is real and mighty, the same person who speaks and sings in our own timeline for Black Lives Matter, for Time’s Up and the Women’s March.

Monáe in the months leading up to Dirty Computer’s release often told reporters she was terrified of what the response to all of this might be. There was her coming out as pansexual amid her big and Baptist family to fret over, but she also worried about fans. “What if people don’t think I’m as interesting as Cindi Mayweather?” she asked in an April 2018 profile in Rolling Stone.

I might’ve been one of those fans she meant. I wanted to know what happened to Cindi, how she turned out so special and saved the day. ArchAndroid and Electric Lady seemed like soundtracks for pieces of a movie I was desperate to see completed. And I sometimes miss the mystery, musical thicket and downright weirdness in ArchAndroid that drew me in a decade ago. But Dirty Computer’s gains are worth these losses.

And in some ways, the album is the same old Monáe: the numerous collaborations with other artists, the blending of retro and futuristic styles in her own flavor of Afrofuturism, the drive to see and celebrate black and queer and female people. On that last count, such reviewers as Jenna Wortham with The New York Times, Sydnee Monday at NPR and I say she’s succeeded.

I think Monáe in fact gave an ending to that story she started years ago. Cindi, Jane, Janelle — whatever her name, she took the burden of saving the world off of her shoulders and got a free, real life for herself, not without fear, one step at a time, but without apology. “I think I’m kind of discovering the gray and realizing it’s OK not to have all the answers, or to supply them,” she told The Guardian in early 2018. And as always, she invited the rest of us to join her, to march on and to dance.