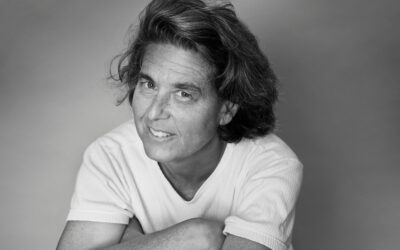

Tomboyland, as the title of Melissa Faliveno’s essay collection implies, is filled with duality and the desire to label — even when words fail to adequately do so. Raised in Mount Horeb, Wisconsin, Faliveno is a native of Tomboyland (her name for the Midwest), and she uses the refrain “Where I come from” throughout her generous yet incisive critique of nearly everyone from the region, including herself. In her journalistic personal essays, she uses her body as both lens and metaphor for the Midwest as well as to consider the ways our culture is frustrated by ambiguity.

In the titular essay, Faliveno wrestles with how difficult it is to eradicate the shame she has about “the vile and blasphemous fact of [her] body,” as she’s made to feel because of her androgynous appearance. Yet her androgynous body somewhat fits with those of the women where she comes from, strong women “built like barns, built to work.” Labeled — even insulted and heckled — by others based on her appearance, Faliveno finds existing language insufficient to describe herself. “Genderqueer” doesn’t feel quite right, while feminine pronouns and her name “somehow feel like mine,” she says. In this way, her body is much like the Midwest, “a place that transcends boundaries, that defies definition, a body that holds within it a multitude of identities.”

In her mid-20s, Faliveno moved from Madison to New York City, where she suddenly “felt unremarkable at best and backwoods at worst,” borne from a new awareness of how the coastal elite view Middle Americans. This view worsened after the 2016 election, when “people on the coasts began to talk about Midwesterners as if they were nothing more than uneducated, gun-toting rednecks,” Faliveno writes in her still timely essay “Gun Country.” She became protective of the Midwestern gun owners she loves and calls attention to how integral guns are to midwestern culture because of hunting, which is “holier than holidays.” Through conversations with friends and family like her partner’s veteran father, a Wisconsin woman transplanted from Brooklyn, and “a rare man” — a bisexual veteran, Faliveno paints a portrait of gun ownership that differs from liberals’ stereotypes. Her defense of gun-owning midwesterners is successful because she examines herself, too, and distinguishes between gun ownership and gun violence and the ways they overlap. To write the essay, she shoots guns herself, noting how powerful it makes her feel and how much she liked being good at it. Even as she crafts this nuanced portrait that allows for gray area, she underscores the fatal flaw of gun ownership: rage. She admits her own rage might have been devastating if she’d had a gun during fights. Most threatening, though, is the rage of men who are usually white. But this rage doesn’t produce a binary where gun owners and ownership are either wholly good or bad. It’s a binary that doesn’t exist, Faliveno states, even though the problem endures.

Of course, Faliveno’s examination of the Midwest would be incomplete without one of the most iconic Midwestern fixtures: tornadoes. She begins Tomboyland with them in the essay “The Finger of God,” and tornadoes’ significance to the collection becomes clearly apparent by the end.

“I began to realize that even the sturdiest structures, like family and home, could be blown away in an instant,” Faliveno writes.

She goes on to unveil the unsoundness of other structures, revealing the importance of the “Midwestern nice culture” sentiment while also underscoring the importance of questioning the systems we live in. She synthesizes the diverse perspectives of all those she interviews along with her own as she fledges from the Midwest then returns with a more fully realized body. Faliveno captures a stolen land and a disappearing one where farmlands are eaten by development. “I worry, sometimes,” she writes, “that the next time I come home there will be nothing left at all.”

As much as Tomboyland is about the in-between of the Midwest, it’s also about queerness in places that resist duality. Faliveno unpacks the harassment, erasure and judgment she experiences as a bisexual person from straight and queer communities in both Wisconsin and New York City. She is anxious to reveal that she’s in a relationship with a man, since she “will be questioned or invalidated or both,” so sometimes she keeps this fact “like a secret.” She points out that “[l]ike so many of the systems in which we live, oppression is tricking the oppressed into oppressing each other.” Still, gender is a system that gives her meaning, which provides another parallel to a Midwestern binary: carnivore and vegetarian/veganism, a dichotomy her “meat and potatoes” upbringing didn’t prepare her for. Inspired by her mother’s admission that she stopped contemplating the ethics of eating meat when she realized she would have to change her whole life, Faliveno observes that “it’s easier to exist within the structures we’re given” and that not doing so may “dismantle our entire way of life.” Taken together, Faliveno’s essays examine how the way we view people’s bodies can be as fraught and divisive as our conception of place, along with the assumptions we make about the people who live there.