For no reason at all, I pulled open a drawer I’d not touched in a decade and found myself poring through my parents’ high school yearbooks. Reading through the short comments of well-wishing students, I turned back to the address of the principal of Weequahic1 High. I noticed the date, January 1942. “You will face problems that will seem insoluble but will have to be solved,” he wrote. He was preparing them for war. “You will have to build a new world,” he wrote, enlisting Churchill’s barely dusted-off phrase, “with blood, sweat, and tears.” He then linked times characterized by adversity with the opportunity for a consequential life. It struck me how this paradox seemed to resonate with both our current times and the material of Carolyn J. Lewis’s book of stories.

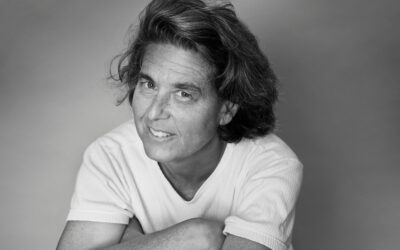

Before she left Long Island to return to the cherry capital of our country, northern Michigan — where she was a member of the sixth generation of a farming family — Carolyn gave me a large book to fill with my writings. I’d originally sought her out about 20 years ago. I had a column on “women in the arts” in a small, now folded, monthly women’s newspaper. I’d interviewed upwards of 50 artists, but until Carolyn, I hadn’t yet found a writer. Thus began our friendship, most of which took place

- According to Wikipedia, Weequahic is derived from a Lenape word “wee-qua-chick” meaning “head of the cove.” The high school is the one Philip Roth graduated from less than a decade later.

through correspondence. In late March 2019, Carolyn passed away from the complications of early onset dementia likely exacerbated by chemotherapy for breast cancer.

In addition to her expertise about cherry farming, Carolyn was a lawyer, and she made her living as a freelance editor. Though she wrote masterful stories, she had yet to publish a book. The publication of her book happened by way of her husband — the writer Stephen Lewis — who not only became her caregiver but took it upon himself to find Carolyn’s work a publisher. The Wolfkeeper was published by Mission Point Press three months after Carolyn’s death. Of the 10 stories in this collection, five had been published in literary journals, one of which was a semi-finalist in several literary competitions.

Generally speaking, these stories present a cast of quirky, charming characters, some of whom we see multiple times throughout the stories, but the dominating force is the natural world, the land and its lover — the great lake. The lens through which we behold this world holds a clarity that imbues itself in each word. The words urge us to slow down, to take the puzzle pieces and fondle them — replete with imagery, sound and the occasional understatement — leaving us to finish the stories ourselves.

While reading, I’m taken to a time and place that is otherwise unrecognizable. The land is both pristine and unforgiving, and an unearthly community exists between the geography and its two- and four-legged inhabitants.

These stories read like myths, partly due to the texture and luminosity of the prose, along with the compression that asks us to create this world in our minds, to see its pictures, to smell its smells and hear its sounds. We are taken far north to a part of the U.S. that shares a watery border with Canada, a terrain that is more often than not covered with snow, where horses pull a sled runner across the ice, and sometimes the ice melts or breaks, and sometimes there’s a seam through which a ton of lumber falls. These stories are populated by lumbermen and fishermen and impoverished families where there is abuse, where religion is known more for the harm it does than for salvation. These are stories of Jesuits and Indigenous peoples, some where there is a mix within the same family. There is a story with a body that must be chipped from the ice, a story about a bet that will become as deadly as the weather, about women running a “Tavern of Dreams,” about the wives of the “King of the Mormons” left to fend for themselves on an island in Lake Michigan in the dead of winter.

One sees here a tenderness, a ferocious love of place and respect for its denizens who thrive here. The first story envelops the reader in a sanctified world where a very old man is living out his days in a cabin with a swinging door. It is cold, “for winter had not yet invited spring in.” A young woman appears whose job it seems is to stoke the fire and make sure the man will not starve. She leaves a number of warm loaves of bread stored in a vine basket above the hearth, some of which he proffers to the wolf who visits him and seems to know this man well.

There is a life force that makes itself evident in each of these stories. The dusk has a mouth. The cries of wolves “float down” from the cliffs.

The voice of Carolyn J. Lewis’s stories is the voice of the land. If it could speak, in a language we might intuit, it would use her voice, it would say we connect — the land sees to that. It calls us to itself. We rise to the demands of time and place, what in fiction we call the setting. In Carolyn’s book, it’s the interaction between setting and character that remains so defining, so revelatory.

One could say that setting provides the challenge of our lives even now. That which is difficult presents as an opportunity, directs us to see beyond the moment, beyond mortality, beyond fear, even — offers a connection to what some have called grace: whether it is through World War II, whether it is a great lake melting under us, whether it is Covid-19, whether it is Black Lives Matter, whether it’s a liminal moment in our very democracy. We make a choice in this moment of clarity when we glimpse the fragility of human bodies, of human institutions, of human civilization; we respond with something more noble than the insatiable appetites of the self.

We will look back one day. We will see what was once insoluble. We will see how we changed our world.

In her introductory epigraph, Carolyn writes: In the land there is a longing/and the longing is in the people,/and the people who come to it/ have a name for it they never speak.