When we seek to make sense of the geographical world, we turn to maps. Their lines, bold or fine, solid or dashed, provide a comforting order. We feel that we know where things are, and how those things are situated to us. Maps, with the plethora of literature and media about places near and far away that accompany them, are all designed to inform us of our situation in the world, and often serve to allow us to accept the world, and our place in it, without question.

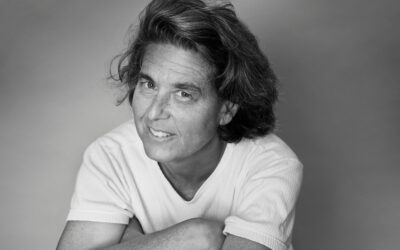

A tale of a life-changing journey through the backroads of a Caribbean island, Allison Coffelt’s lyrically composed Maps Are Lines We Draw seems poised to fit into the well-stocked shelves of the travel memoir section. The book details a road trip through Haiti motivated by the author’s childhood fascination with the island, and the desire to observe and participate in ongoing humanitarian work. Coffelt’s own focused awareness of the function of her genre, and the implications of her own viewpoint, prevent this book from becoming just another tome in the library of complacency. The book provokes questions rather than simply giving us a set of answers.

Coffelt outlines the events of the trip itself over the course of thirteen short chapters. The facts of her journey, the events themselves as she experienced them, are rendered plainly, largely concerning her time spent with Dr. Jean Gardy Marius, a Haitian doctor who founded the medical organization: Organizasyon Sante Popilè (Public Health Organization).

The dialogues between Coffelt and Dr. Marius, or “Gardy,” are deep, often emotional exchanges, whether haggling for fruit at a roadside stand, exploring Gardy’s own personal history or encountering the reality of impoverished life on the island in various ways. These conversations, and the experience of assisting Gardy and his team run their affordable medical clinics, form the narrative core of the book.

In an abbreviated, rhythmic style that occasionally flirts with prose poetry, Coffelt interpolates historical facts among Gardy’s narrative, such as the Haitian Revolution’s impact on French colonial policy, leading to the Louisiana Purchase and the U.N.’s role in a deadly cholera outbreak in the wake of the 2010 earthquake is. In the context of OSAPO’s sacrifices, this is especially devastating and challenges the narratives of aid told to us through fundraisers and mission trips.

The synthesis of personal travel narrative and the poetic insertion of blunt historical facts and figures forms the basis for the author’s exploration of the difference between “us” and “them,” “here” and “there.” At its best, Maps illuminates the way we, with the society we belong to, relate to those at the margins of the global economy. Coffelt draws attention to the “lines we draw” between ourselves and the world around us and how those lines, those boundaries, serve to enable abuse and exploitation. Complicating the easy notion of “foreign aid,” the book demonstrates the uncomfortable reality that such aid, and narratives about such aid, often serve as much to benefit the giver as the recipient.

In Maps, Coffelt attempts to break down, or deconstruct, the notion that a place like Haiti is that much different or that far away from “us,” the reader, wherever we may be. The effort may falter when the author personalizes too much, individualizes too much, becoming susceptible to the self-exploration narrative of the travel genre. Coffelt’s description of her own emotional reaction to internet images of Haitian hurricane victims is far less powerful than her exploration of the Haitian island and people themselves, for example. Most of the time, Coffelt’s technique subverts this tendency by challenging the reader not to find in Haiti just another place to express themselves, requiring them to adjust their conception of the space, the lines, between us as global citizens.

In this sense, Coffelt wants to do away with maps, and the lines on them that inevitably strengthen systems of inequality. She invites us to interact with the world in much the same way she recalls interacting with her globe as a child: “run your fingers along its curve or spin it until the lines and words are all a blur.”