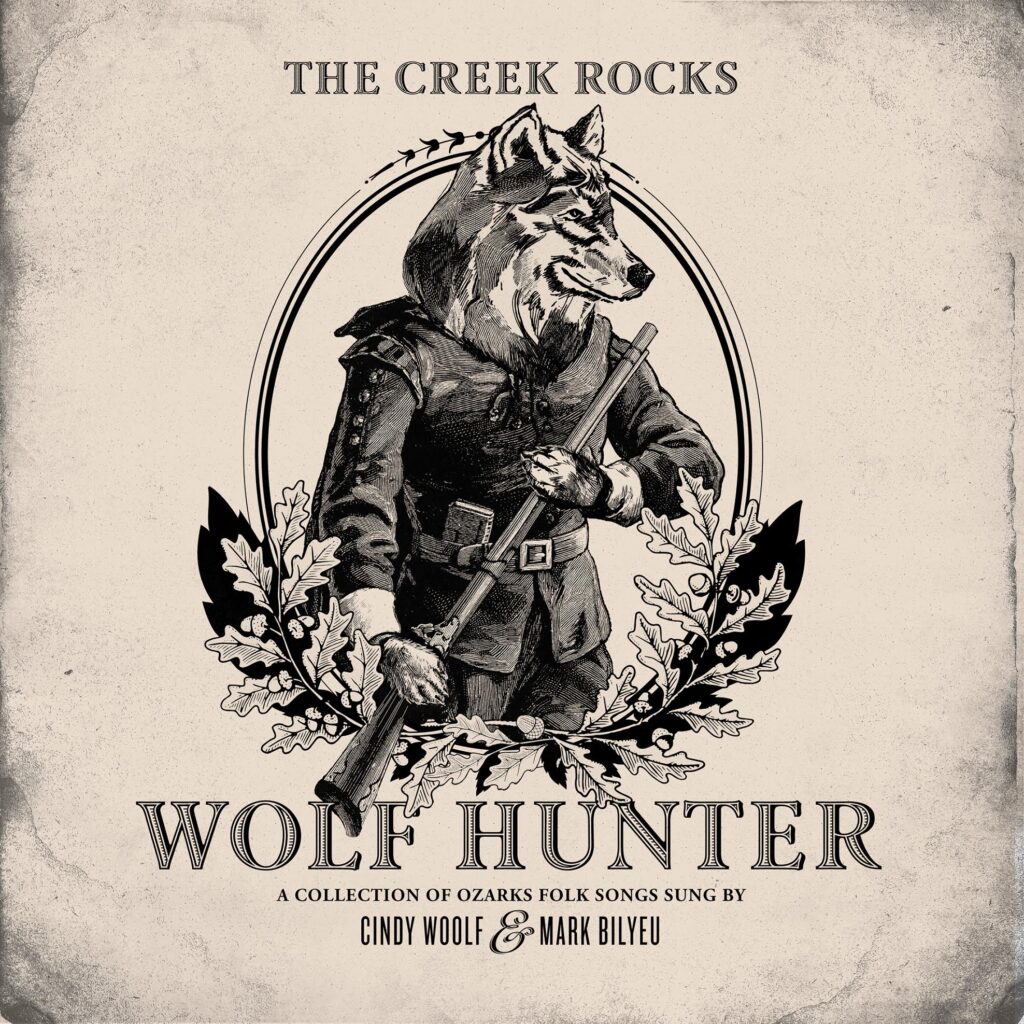

If you do not believe that a dusty collection of 16 traditional folk songs can be called a concept album, perhaps you underestimate this region’s deep well of banjo tunes about woodland creatures. Wolf Hunter is a concept album by virtue of its curation: the songs have a cohesion of theme (namely, an abundance of critters) and geographical roots (specifically, the Ozarks). They are almost entirely combed from the archives of John Quincy Wolf and Max Hunter, mid-century folklorists from Arkansas and Missouri, respectively, who were both lauded in their lifetime for capturing the distinct sound of the Ozarks in the 1950s and 60s.

A half-century later, Southwest Missouri’s veteran visionaries of roots music Cindy Woolf and Mark Bilyeu, performing as The Creek Rocks, have presented a set that proves this distinct Ozark sound endures. Wolf Hunter is stuffed full of regional references, down from the hills and into the backwoods. From “Little Rock Rock” to “The State of Missouri,” these are songs set in green pine tree groves filled with blue jays. There are multiple encounters with wild hogs. Set to the bright, plucky banjo and the bopping double bass thumps, the songs sure do sound like their homeland.

The Creek Rocks are not the first to see popular potential in a folklore library. The recordings collected by Wolf and Hunter helped introduce arrangements of standards like “Casey Jones” and “Roving Gambler” that would be reinterpreted by everyone from the Grateful Dead to Billie Joe Armstrong. Their folklorist contemporary Alan Lomax, most notably, has enjoyed perennial relevance, from references on Jay-Z and Kanye West’s collaboration Watch the Throne to the songs heavily sampled on Moby’s 1999 electronic album Play.

Even still, young listeners may not recognize just how influential these original recordings really were. Today, any

imaginable sound is just a few clicks away. Following musical breadcrumbs back through an artist’s influences is not only possible, but popularized: streaming services suggest similar artists; listeners are prompted with related videos or albums. While listening to Wolf Hunter, you can search and compare older interpretations of opener “Can’t You Hear Them Wolves

A-Howlin’” before the song is even over.

In the analog 1950s, the work of folklorists like Wolf and Hunter was essential to broadening roots music. For curious ears unseasoned to a distinct regional sound, such folk songs provided the discovery of a new musical landscape. And for those living in the Ozarks, folks whose sonic spines were built by the songs they grew up singing, these recorded archives provided recognition, and the promise of posterity.

This is not to suggest Wolf Hunter is an unfeeling, academic affair. When Cindy Woolf ’s voice takes center stage, her twangy affectation calls to mind both Dolly Parton’s frisky sweetness and Iris DeMent’s raw traditionalism. The arrangements stick close to Americana convention: strings drop out to foreground airtight harmonies; there are no wandering solos or unconventional instruments. But flashes of postmodern twists—like a horn sounded at the beginning of “Groundhog,” or the whimsical studio effects of “Where’d You Get That Hat?”— lend the piece a certain freshness. More importantly, both Woolf and Bilyeu grew up in the Ozark hills, and you can hear it in their earnest performances.

For Mark Bilyeu, formerly of beloved band Big Smith, to tackle a set of Ozarks songs seems not only logical, but probably inevitable. After all, it’s in his blood: the last track, breezy pastoral “Tie-Hacker’s Joy,” is recorded here for the first time, passed on to Bilyeu by his father, attributed to his great-great uncle.

Such passed-down songs are just one aspect that makes The Creek Rocks a family affair. Have I mentioned that Woolf and Bilyeau are married? When their voices coalesce on “Zelma Lee,” cooing to one another, “Her smile is sweet and tender as the moonlight on the sea,” we feel cooed to, too. It’s like watching daddy sing bass and mama sing tenor on the front porch.

Wolf Hunter celebrates the necessity of analog traditions, from singalongs to storytelling. In the beautifully designed liner notes, each track is described with an adjoining anecdote about the place, recording or family member it came from. The listener is reminded of why we sing folk songs in the first place: to mark where we come from, and remember it’s not so different from where we are now.

Much like the recordings of Lomax or Hunter helped define a regional musical character, The Creek Rocks remind us of our shared traditions. Their album is conceptual not only in its curation, but also its intention. This is the sound of Ozark history, the soundtrack of us getting from there to here. Wolf Hunter is distinct as a concept album in that it is filled with warmth and heart. It never holds you at arm’s length, but brings you in for a bear hug, begging you and little brother to join right in.