Lorine Niedecker

River Cabin

Blackhawk Island, WI

By Shanley Wells-Rau

I was the solitary plover

a pencil

______for a wing-bone

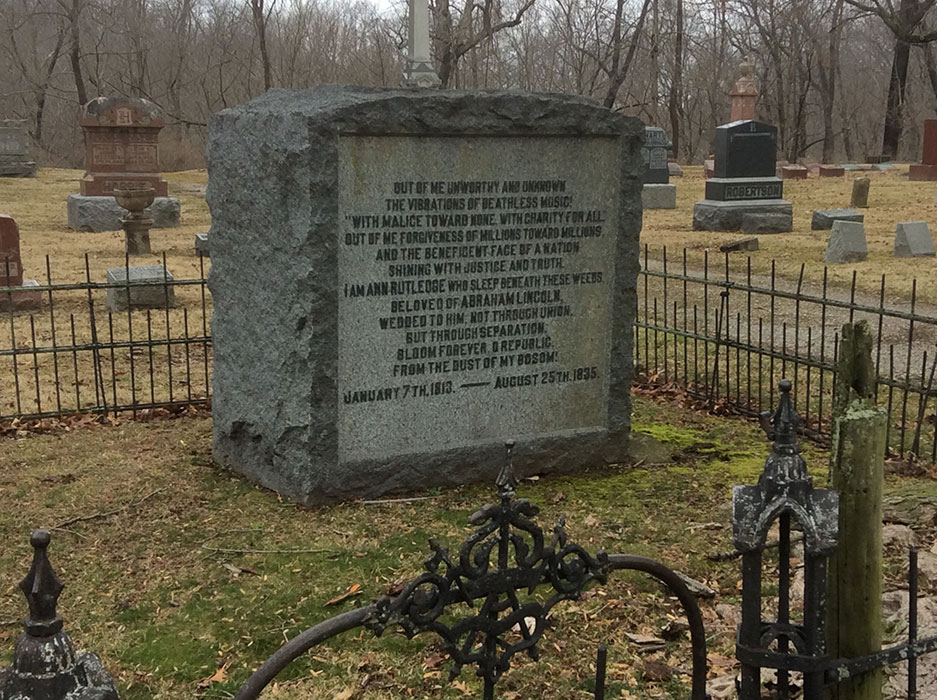

What more solitary place than a small off-grid cabin on an island that’s not really an island jutting into a lake that’s not really a lake. The cabin was a writing sanctuary for Lorine Niedecker (1903-1970), said to be America’s greatest unknown poet, who will forever be linked to Blackhawk Island in southeast Wisconsin.

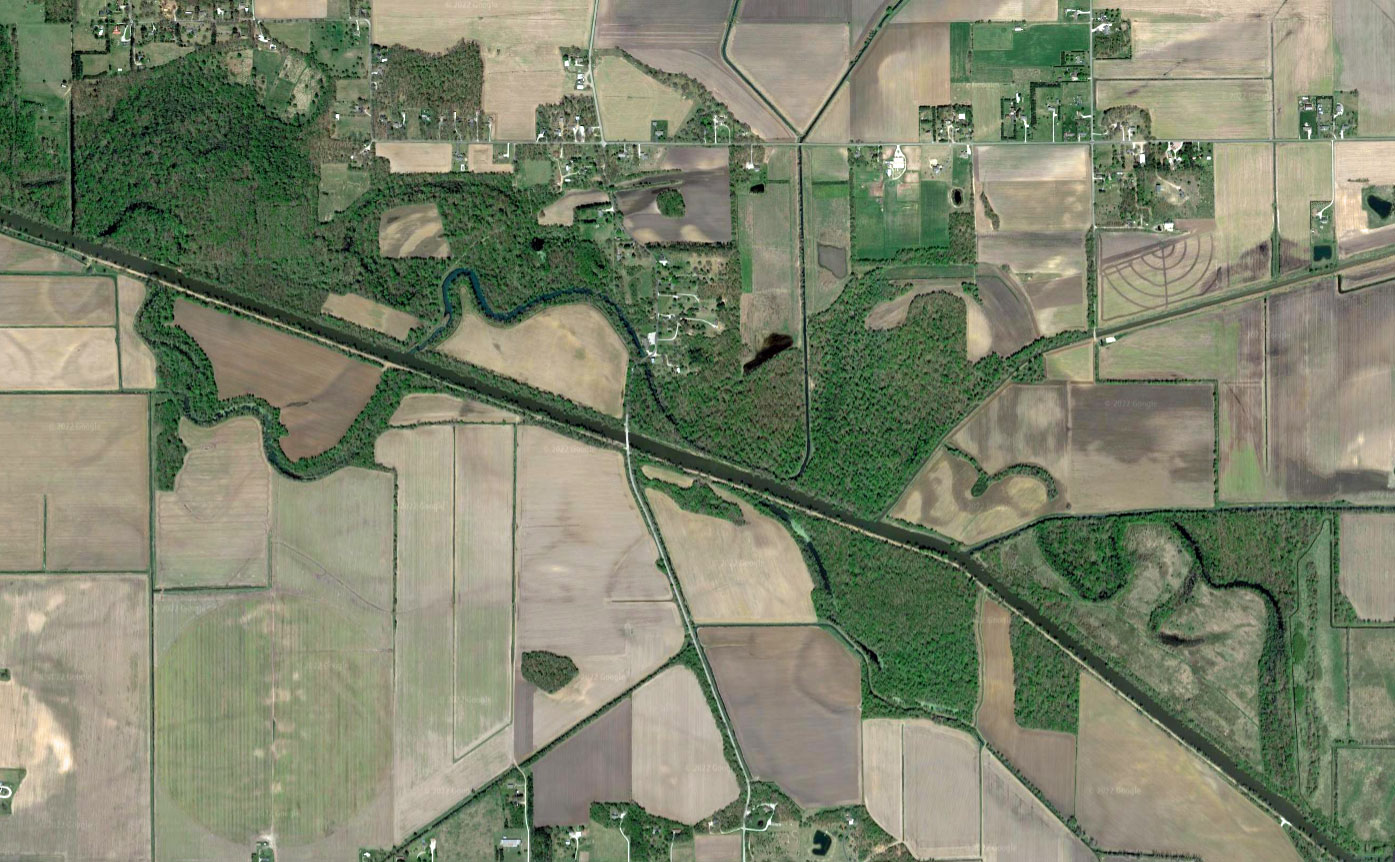

Look at Blackhawk Island on a map and you’ll see it’s actually more of a peninsula that points into what is called Lake Koshkonong, an open water area that is really just the Rock River being messy all over its flood plain. The river likes to outstretch itself and in its flood-prone ways created a recreational haven for boaters and fishers.

Placed less than 100 feet from the Rock River, Niedecker’s cabin was bought as a kit from a catalog and assembled by her father in 1946. He sited it closer to the road than the river in hopes of preventing displacement during the regular floods of spring. Elevated on concrete feet, the 20×20 one-room house hovers over four cement steps. The front and only door faces east, away from the river, as if to shrug off the idea of annual flooding. This one room contained her life: bed, books, table, typewriter, sink, pencils, hand-held magnifying glass. With no running water, she hauled buckets as needed from her parents’ house across the road. That was the house she grew up in. The house she needed to escape.

Her father, a congenial carp seiner and fisherman’s guide who was inept with finances, was carrying on an affair with a married neighbor close in age to his daughter. This neighbor and her husband were milking Henry Niedecker of property and money. Her mother, Daisy, had lost her hearing after her only child’s birth and turned her head away from her husband. Her “big blind ears” couldn’t hear what her eyes couldn’t see. A lifetime of fighting flood mud, “buckled floors,” and increasing poverty seem to have settled around her like a mourning shawl.

Niedecker left the area a few times—for college until the family’s finances made her quit (early 1920s), for artistic and romantic companionship with a fellow poet in NYC (early 1930s), for work as a writer and research editor for the WPA in Madison (1938-1942), and finally for Milwaukee in 1963 when she married a man who lived and worked there. But that spit of land brought her back after each exodus. Once married, Niedecker and her husband, Al Millen, returned to the river every weekend, eventually building a cottage riverside just steps from her cabin. They moved into the cottage for good in 1968 when Millen retired. Niedecker lived there until her death on Dec. 31, 1970.

In the opening lines of her autobiographical poem “Paean to Place,” Niedecker submerges herself deep inside a location she said she “never seemed to really get away from.”

Fish

____fowl

________flood

____Water lily mud

My life

____

in the leaves and on water

My mother and I

_________________born

____

in swale and swamp and sworn

to water

Painted green when built, the cabin today is chocolate brown. Sturdy wood, unfinished inside. A brass plaque by the door shines with the lines: “New-sawed / clean-smelling house / sweet cedar pink / flesh tint / I love you.” Her signature is embossed below. When I visited, it was hot and dry. The riverside window was open, allowing a breeze to push stifling July heat into the plywood corners. A lovely space. I could see myself writing there. I told myself I could even manage life with “becky,” as she called her outhouse.

It’s not hard to imagine the constant cleanup from the river’s yearly ice melt and flooding. Tall maples and willows accustomed to watery life block the sun over a dirt yard that would easily mud with rain. The only access to sunshine seemed to be on the riverbank or in a boat on the river itself. The tree canopy jittered with life, a “noise-storm” as Niedecker once wrote to a friend. I looked to see what birds were holding conference, hoping to meet one of the famous plovers so linked to her work. I saw none. Just movement, shadows, and chittering, and I thought of her technique to overcome her own failing eyesight by memorizing bird song. She could see birds as they took flight. Sitting still, they were invisible to her except through their calls and conversations with one another.

I grew in green

slide and slant

_____of shore and shade

Neighbors saw her walking, always walking, stopping to peer in close at some flowering plant. She bent in—nose distance—to see past her own bad eyesight. Before her marriage to Millen, she worked as a hospital janitor in Ft. Atkinson. Her failing eyes required that she work with her body, no longer able to serve as a librarian’s assistant as she did in in the late 1920s or a magazine proofreader as in the late 1940s. Her eyesight wouldn’t allow her to drive. If a ride wasn’t available, she walked the four miles to work. Four miles home again.

Out-of-place electric guitar riffs float past underbrush the afternoon of my visit. Someone is listening to Led Zeppelin’s “Kashmir,” seemingly not at peace with bird song or tree breeze. The blaring music makes me think of Lorine’s struggle with disrespectful vacationers and rude neighbors. She persisted in centering poetry inside her hardworking life in a community slowly turning blue-collar loud. Her neighbors didn’t know she was writing her way into the poetry canon.

The current owners are descendants of the couple who bought the property in 1986 from Millen’s estate. They kindly allow poets on pilgrimage, and they seem to care lovingly for the property. As I walked to the river to meet it up close, the owner appeared with a genial greeting. He asked if I’d noticed the 1959 flood marks on the wall inside the cabin. I hadn’t. Eagerly, he guided me back to Niedecker’s “sweet cedar pink” to show me that and other details. After friendly conversation, I decided to head back to town. I didn’t need to meet the river up close. I’ve already met it many times in her poetry.

After a career in the oil industry, Shanley Wells-Rau earned her MFA in poetry at Oklahoma State University, where she served as an editorial assistant for Cimarron Review. Her poetry has been published or forthcoming in The Maine Review, Bluestem Magazine, Poetry Quarterly, and Plants & Poetry, among others. She teaches literature and writing for OLLI and OSU and lives with her husband and a clingy dog outside town on a windy hill, where she wanders the prairie to visit with native flora and fauna.

_____

For further reading, digital archives, and more, please visit the Friends of Lorine Niedecker. Special thanks to Amy Lutzke, who spent a very hot day driving me around and showing me Niedecker’s personal library.

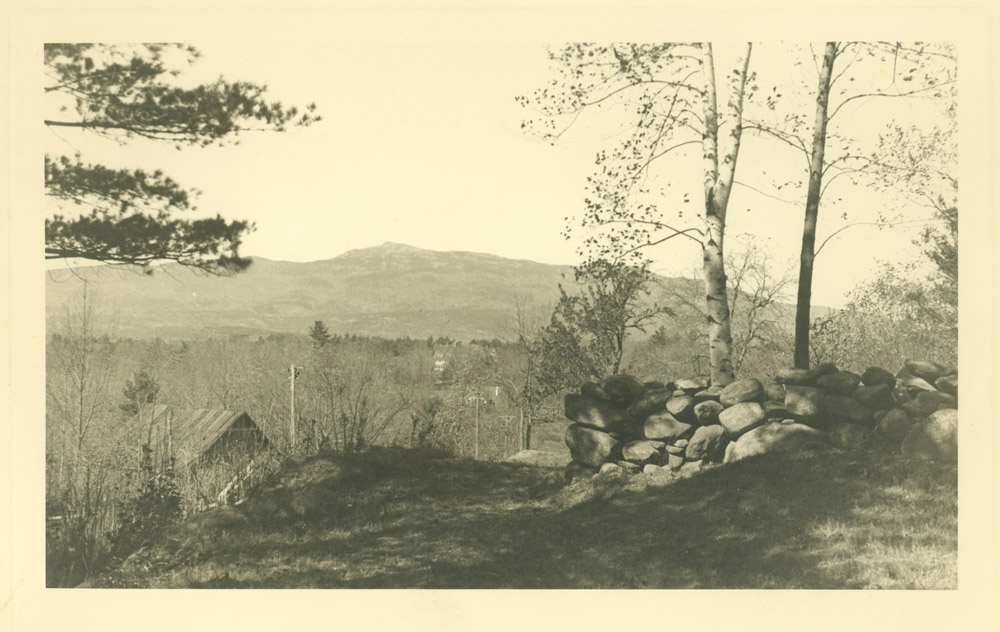

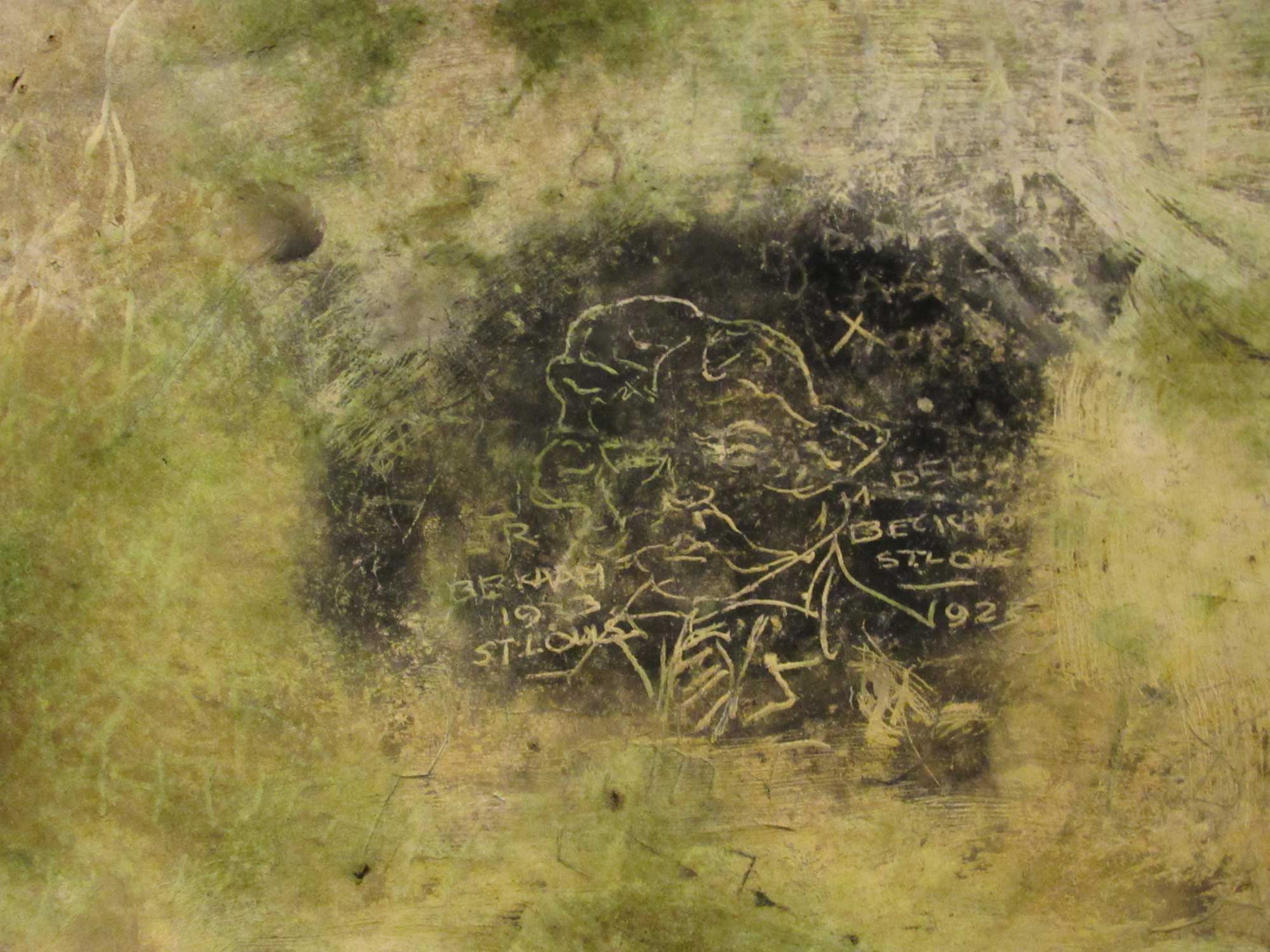

Photograph by Jim Furley, April 1979. Permission granted by Dwight Foster Public Library.