Thomas Hart Benton

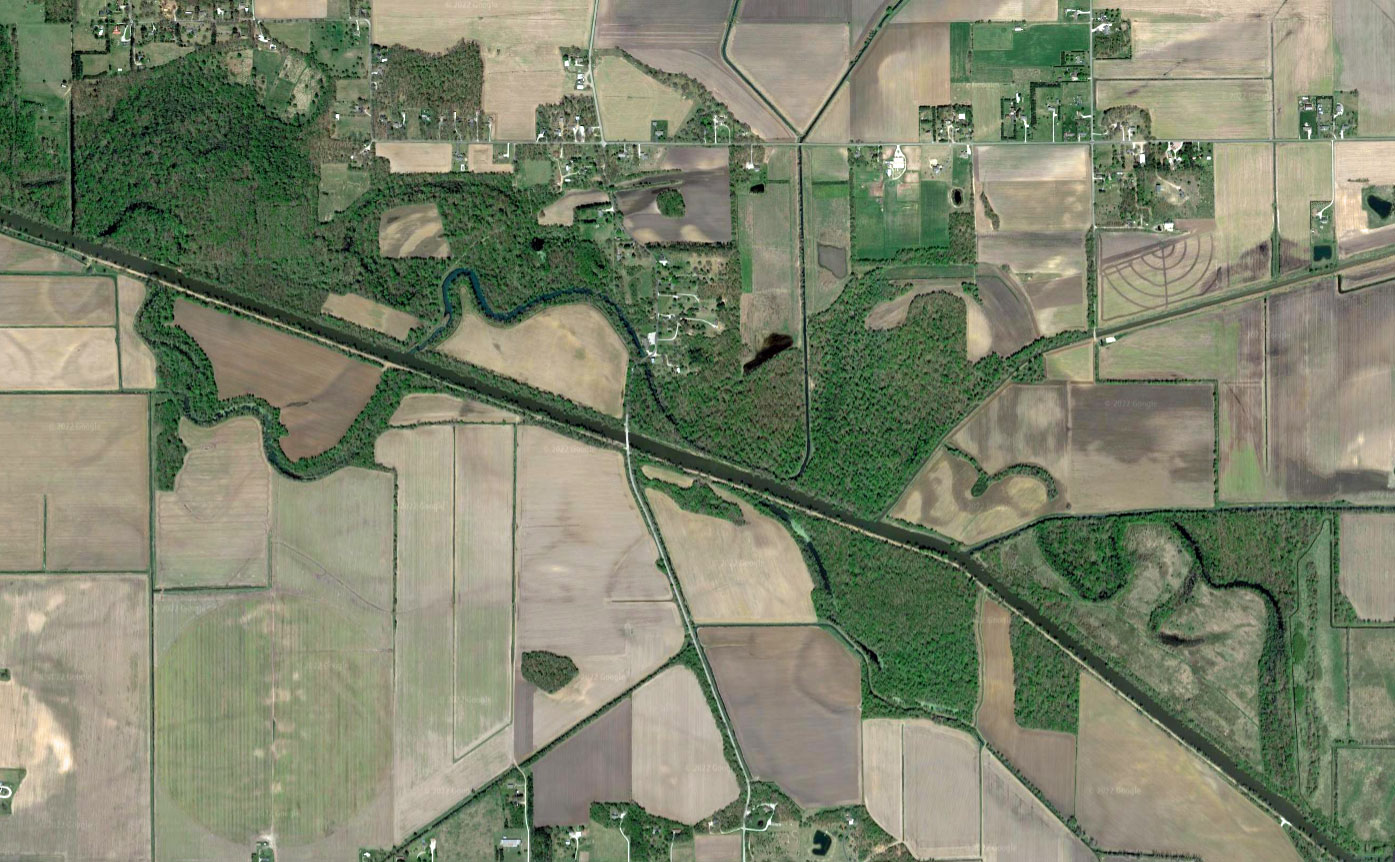

Mark Twain National Forest

Shell Knob, Missouri

By Aaron Hadlow

There is a burled oak tree that stands on the knuckle of a ridge finger behind my parent’s house in Shell Knob, Missouri. Despite its disfigurement, the oak is otherwise straight and tall. Given the oak’s stature, the other trees around it have little choice to stretch for sunlight and grow tall and straight too. As a child, I recall that oak’s bloom of leaves in the spring reached what I perceived, from the Mark Twain National Forest floor, to be a heaven, even if just a lower one. The oak is a waymarker tree and many times growing up I was relieved to pass by it, knowing that the comfort of home was not far. I fear now I would become lost if I tried to find that oak, even though those woods are quite familiar. One may become lost even among the familiar.

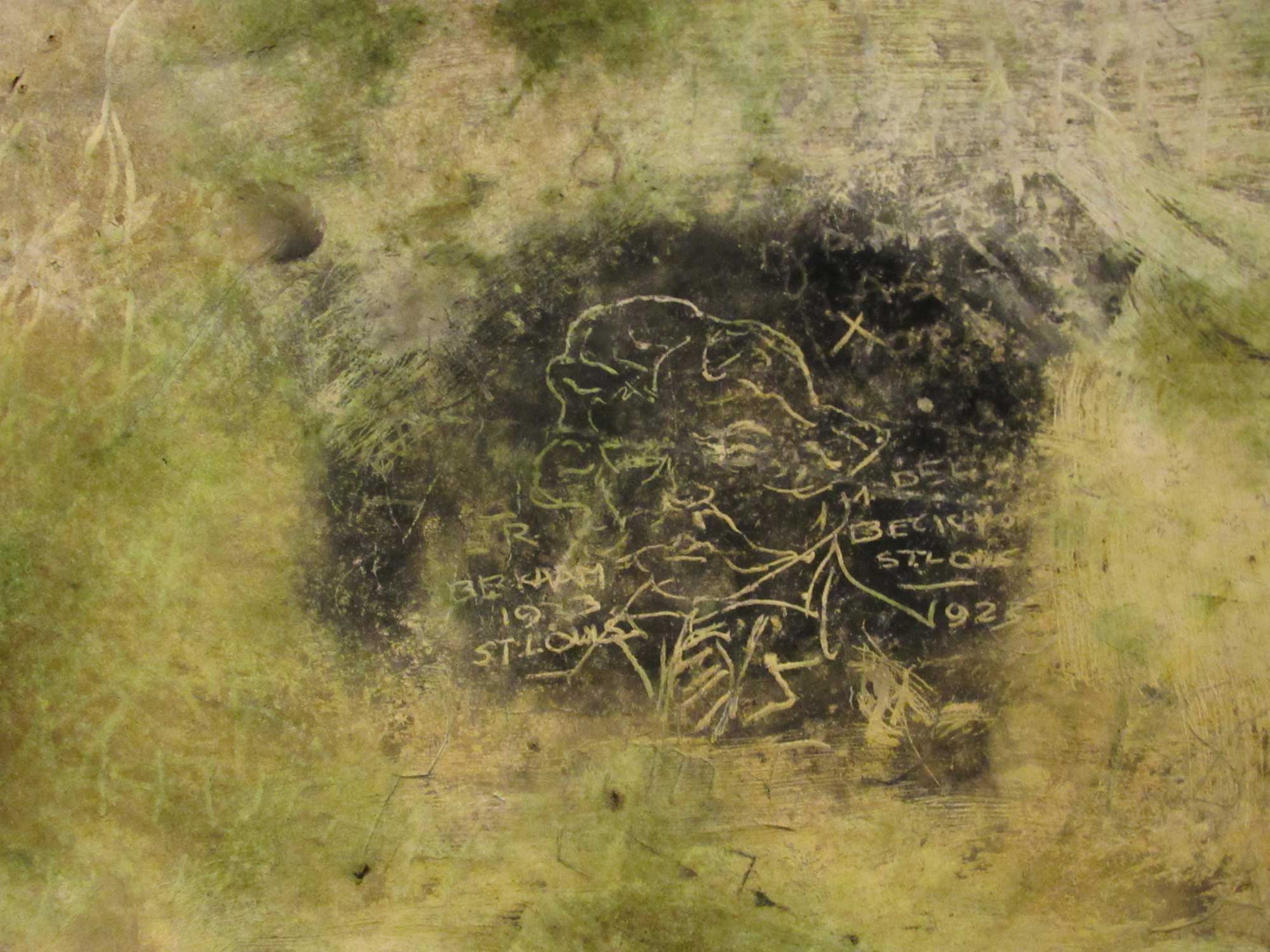

Thomas Hart Benton, one of Missouri’s most storied artists, knew this sense of estrangement all too well. I became acquainted with Benton’s work when I was in elementary school. On a road trip from Southwest Missouri to Columbia to watch the state high school basketball championships, my father stopped at the Capitol building in Jefferson City. My brother and I raced through the wide polished corridors of the Capitol, the stone echoing footsteps and our voices. Our father led us to the Missouri House of Representatives Lounge. Once inside the room, Benton’s many paneled mural, The Social History of the State of Missouri (1936), stilled our feet and voices.

As an adult, I can now see the mural is characterized by Benton’s depiction of laboring bodies. They are often sinewy, in fluid motion, bent under a gravity of some unidentified downward pressure that suggests the yoke of their exploiters. Their bodies rarely find repose, except for a cabal of politicians who sit smoking Roi-Tans and drinking, presumably, bathtub gin. Those bodies yield to the same gravity throughout the work but find a comfortable recumbent ease. The stylistic truth of Benton’s mural is only part of its genius.

But the dissonance is striking between the way Benton writes his own life and the subjects depicted in many of his paintings. This dissonance is best exemplified by an anecdote from his autobiography, An Artist in America (1937), recounting a hike in the woods after he planted the plank of his father’s remains in a respectable cemetery in Neosho, the site of his childhood home.

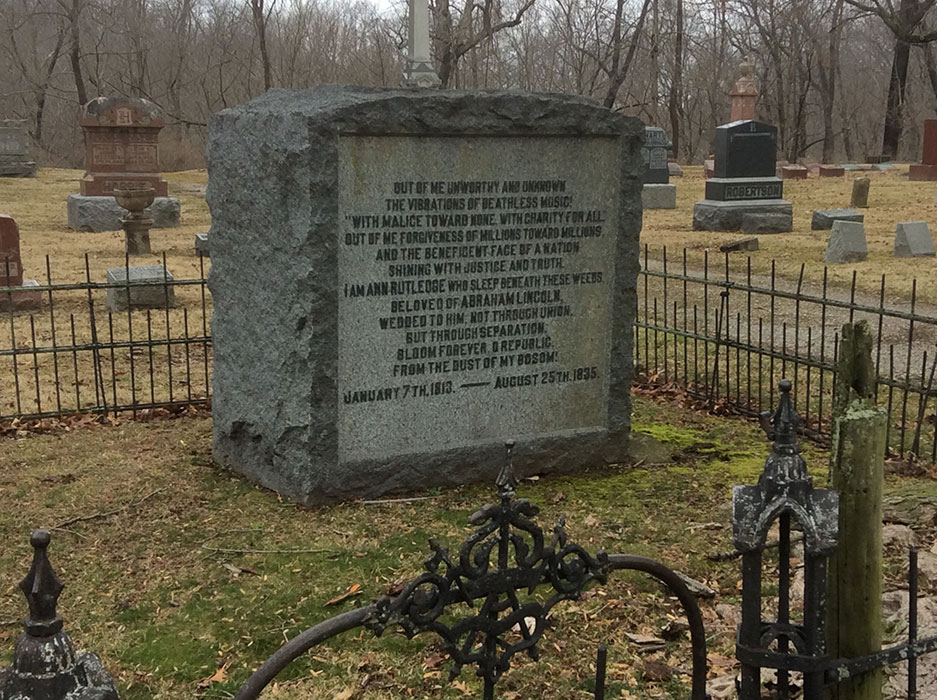

Long-absented from Missouri, Benton had returned to Neosho in 1924 to sit next to his father’s deathbed. Benton’s father was a former U.S. Congressman and as he neared death, his “cronies” also neared to tell stories. In those long hours of vigil, Benton listened, and his father’s friends became his friends. Benton was “moved by a great desire to know more about the America” he’d glimpsed in Neosho. He declared that “for the hangovers of idealistic social theory, Missouri is a grand pickup,” going so far as to laud the “individual will” deeply grooved in the “American character.”

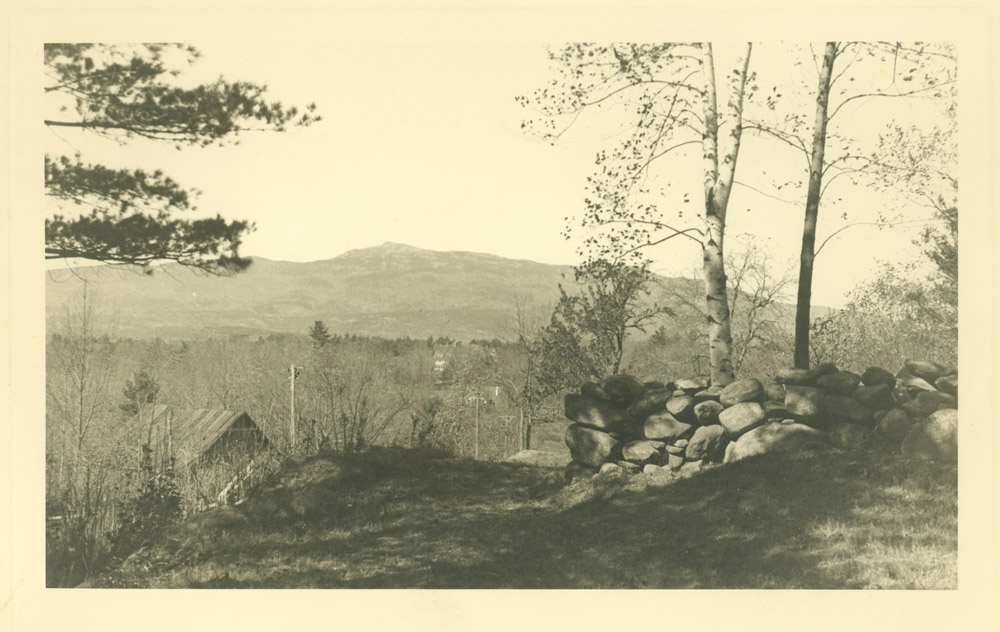

Not long after, the artist set out on a walk in the “White River country along the Arkansas-Missouri line,” in an effort to discover the America he’d been missing. Benton stumbled through the hollows and hills of this area, growing increasingly weary of snakes and cursing the “distrusting” locals, who he blamed for giving him bad directions. He referred to a ferryman who initially denied him passage as a “goddamn son-of-a-bitch” because the ferryman feared Benton was the culprit of a bank robbery the night before. He eventually appraised the locals as “marauding and shiftless hill people,” whose “depredations,” “wild quarrels” and “wild fornications” fill the records of the county courts. Eventually he arrived at his destination in Forsyth. His evaluation of the denizens of the Ozarks was adduced from a hike he estimated to be about 50 miles. I imagine he passed by that burled oak behind my parents’ house near Shell Knob without realizing how close to home he actually was.

In 1935, Benton was commissioned to paint The Social History of the State of Missouri by the Missouri legislature. The windfall that came with the commission must have made it easier for Benton to return to Kansas City to live, though he summered in Martha’s Vineyard until he died in 1975.

Since his death, Benton’s relevance has waxed and waned, leading the editor of my copy of An Artist in America to derogate Benton an “artistic nationalist,” an “irretrievably out-of-date Jeffersonian,” with “nineteenth century” artistic vision. As an irretrievably out-of-date Jeffersonian myself, this all sounds a bit harsh. Of course Benton is problematic for reasons that are self-evident upon reading his autobiography. A privileged heterosexual white man born south of the Mason-Dixon line shortly after the twilight of reconstruction, his ethical blind spots can be easily surmised.

Benton is also regularly criticized for what is thought to be his “provincial” subject matter, verging on caricature. Despite his upbringing in Missouri, Benton’s connection to the America that he is most associated with was attenuated by the path he chose. He fled the Ozarks as soon as he could and only returned for the sort of selective excursions that permitted him to extract experience to fuel his creative work — like a gouty gourmand deigning to visit an ungentrified urban area only for a tasty treat. By the time of his trek through the woods, he’d become all but a stranger to the country. Instead, perhaps the most salient and lasting truth of Benton’s work is the politics of his curved lines. Benton’s strong yet disfigured bodies — bodies that bend down and rise up — defy any theory praising the solitary individual will. It is a truth of form and structure, if not subject. It is the truth of every stand of woods.

Aaron Hadlow is a lawyer and writer. He lives in the Ozarks with his family.