SARAH MORGAN BRYAN PIATT

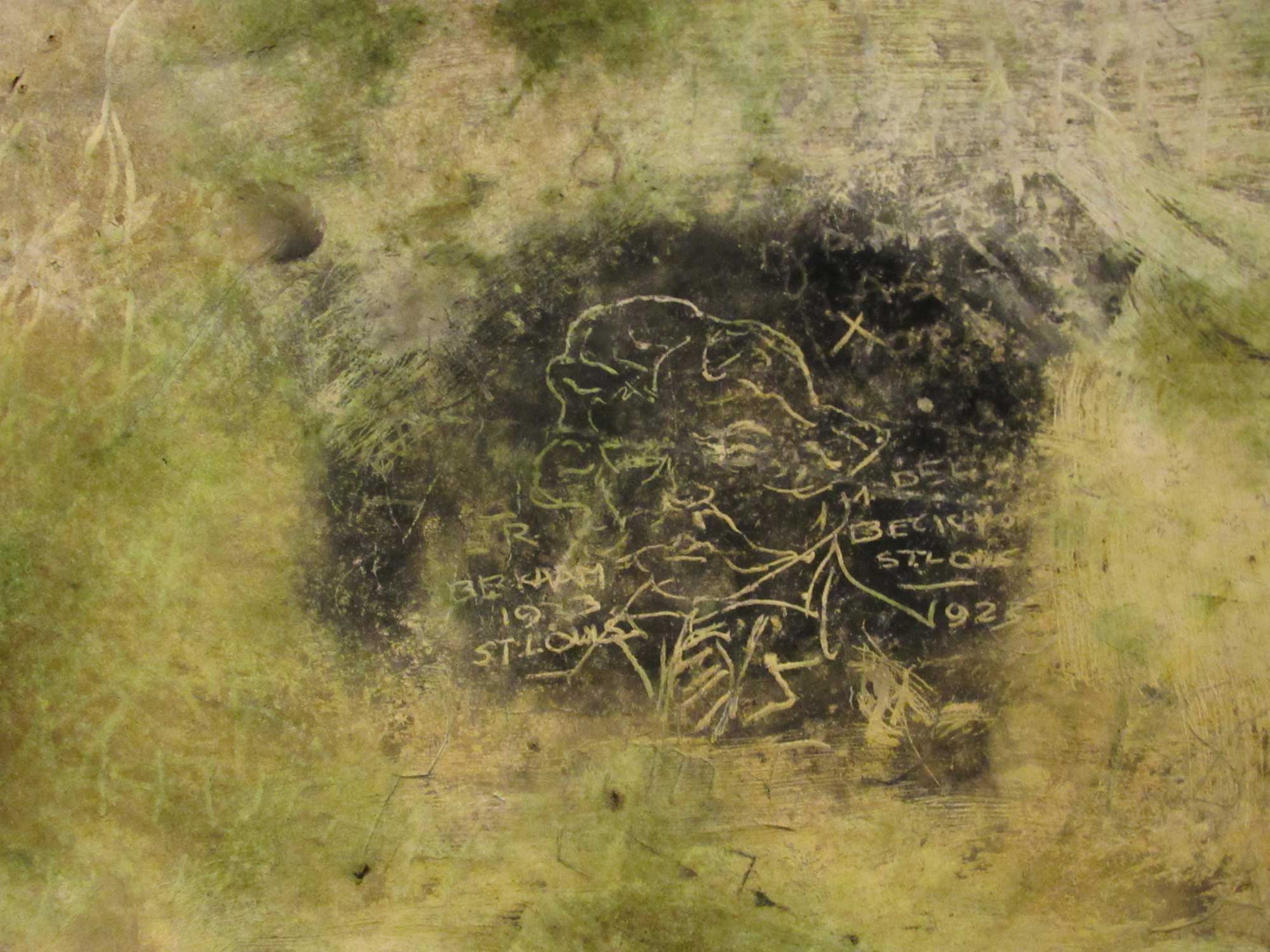

William Henry Harrison Tomb

North Bend, Ohio

By Sean Andres

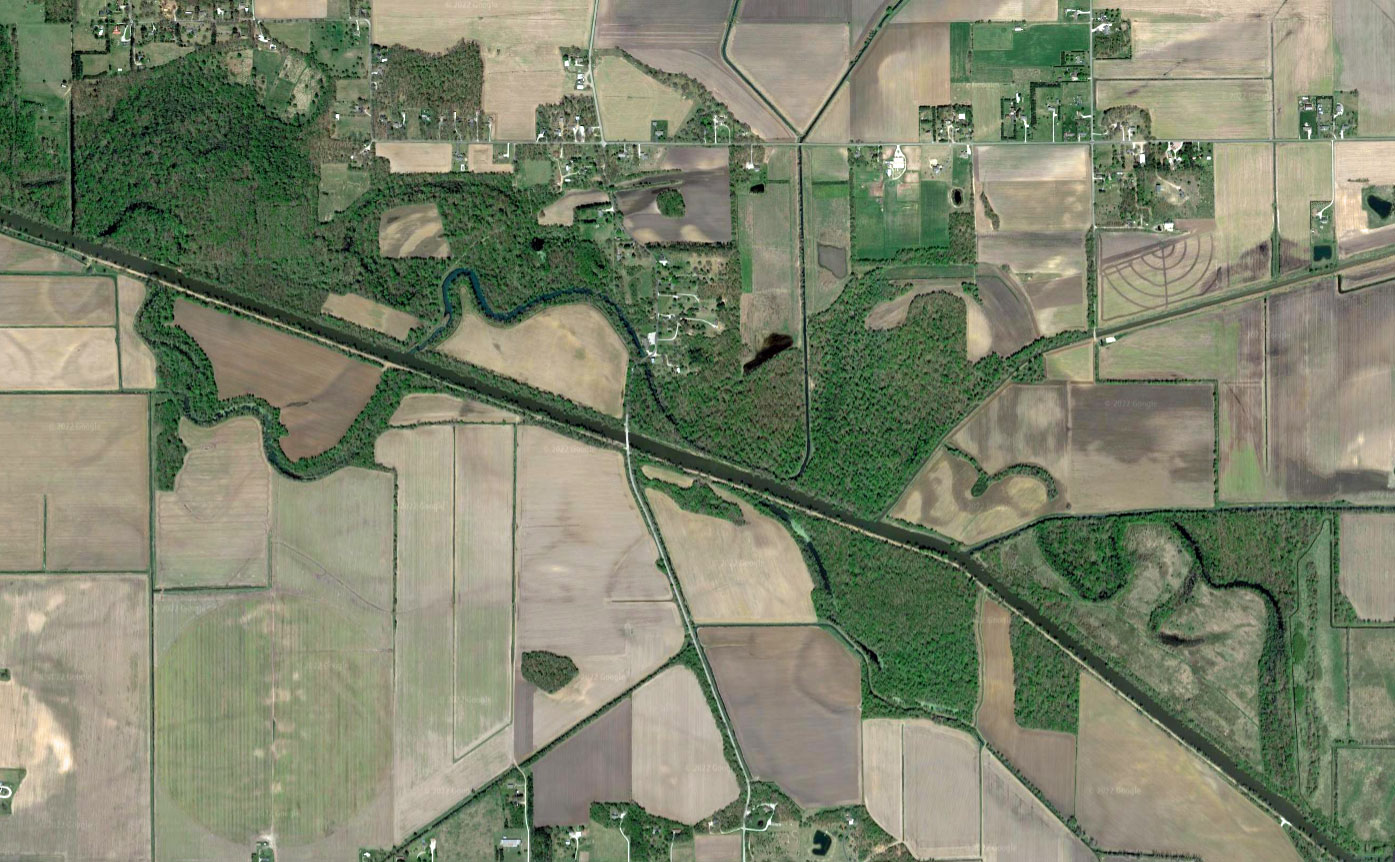

It’s not hard to find something of historical significance in the Cincinnati area, but many people don’t even think about North Bend. The town was founded by John Cleves Symmes, father-in-law of President William Henry Harrison, who swiftly and violently removed, swindled, and stole the land of the Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Territory, including those who had resided where North Bend now stands. As a child, too young to remember and appreciate, I had visited Shawnee Lookout and the William Henry Harrison tomb with my family, and North Bend soon became a town I passed by on the way to the dentist.

But then in 2010, in my second year at Ball State University, I was introduced to little-known poet Sarah Morgan Bryan Piatt in an American Literature course. This was the beginning of a challenging hike up a steep hill. While working on an ongoing project on Cincinnati area women’s history, I delved into Piatt and, through a Piatt family member, began connecting to other researchers.

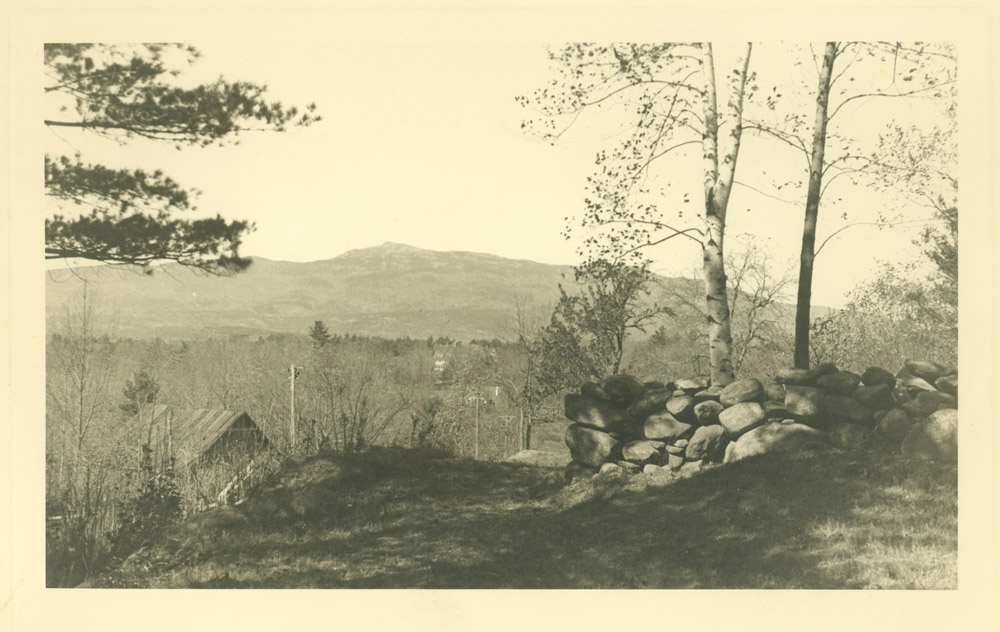

Soon I was enveloped in Piatt’s life and her work, which revealed her to be deeply sympathetic to Indigenous and enslaved peoples and grievously anti-war. Because the most famous woman in the Western world had fallen into obscurity after her death, I was able to uncover over twenty poems and a narrative, from her youth to her late years. When I found out she had lived in North Bend, every time I passed by on the way to the dentist, I wondered whether random houses were hers. Then I learned that one of her houses was a half-mile up Mt. Nebo from Congress Green, where Harrison’s tomb sits on what was believed to be a Native mound. As steamboats passed by, it was customary to fire a salute in his honor.

There, at the tomb, Piatt sings loud in my head with her sympathetic, sharp-tongued wit. I envision North Bend as she might have on her daily walks to the tomb with her husband and their children, spotting the wild rose, wild grape and violets she documented in her poems. The river runs below, and I’m reminded of what the Cincinnati Commercial wrote about Piatt’s writing, that it appears “sweet and peaceful” but proves to be like “the depths of a dark river,” “shadowy and terrible.”

Many people had drowned below that tomb and the Piatts’ home, a weight Sarah carried with her. Still, without doubt, Piatt’s “A President at Home” swells in me.

I pass’d a President’s House to-day —

“A President, mamma, and what is that?”

Oh, it is a man who has to stay

Where bowing beggars hold out the hat

For something — a man who has to be

The Captain of every ship that we

Send with our darling flag to the sea —

The Colonel at home who has to command

Each marching regiment in the land.This President now has a single room,

That is low and not much lighted, I fear;

Yet the butterflies play in the sun and gloom

Of his evergreen avenue, year by year;

And the child-like violets up the hill

Climb, faintly wayward, about him still;

And the bees blow by at the wind’s wide will;

And the cruel river, that drowns men so,

Looks pretty enough in the shadows below.Just one little fellow (named Robin) was there,

In a red Spring vest, and he let me pass

With that charming-careless, high-bred air

Which comes of serving the great. In the grass

He sat, half-singing, with nothing to do

No, I did not see the President too:

His door was lock’d (what I say is true),

And he was asleep, and has been, it appears,

Like Rip Van Winkle, asleep for years!

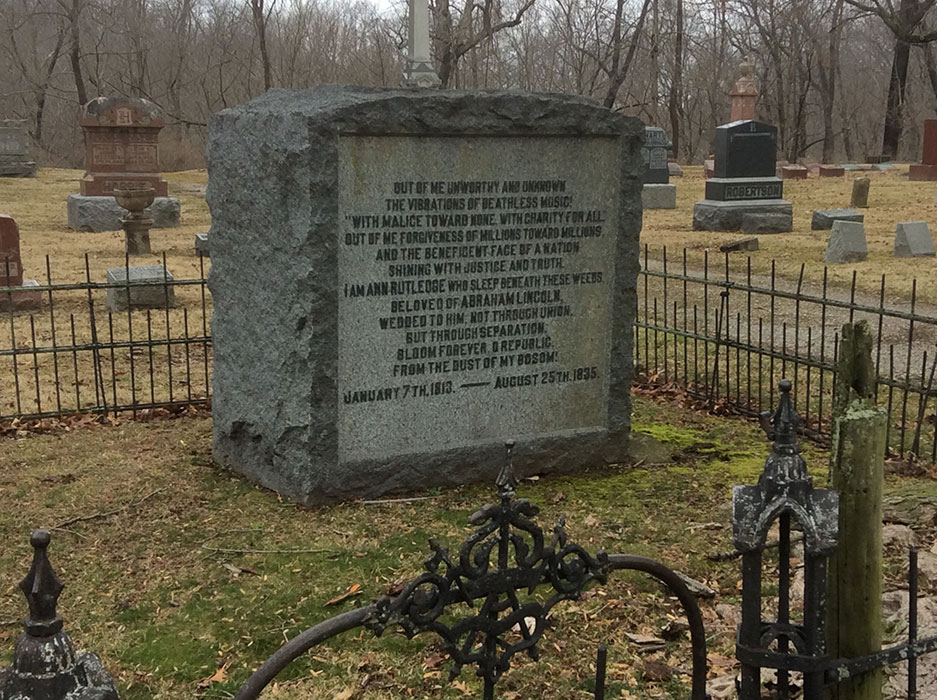

The tomb, for me, is less about the Harrisons and more about the Piatts. It’s hard not to think about her two children, here alluded to as “child-like violets up the hill,” for they lie in unmarked graves beneath a tree somewhere on this “beautiful burial-hill” of grief, as Piatt refers to it in “Death Before Death.”

While the tomb succumbed to the forces of nature, the Piatts continued to keep North Bend historically relevant by placing emphasis on the tomb. Aside from Sarah’s regular visits, her husband J.J. lobbied for the tomb to become a national park, writing a bill that made its way to the Congressional floor. When that failed, he intended to save the old-wood forest around the tomb by purchasing it and turning into a park with proceeds from The Hesperian Tree, a book he edited, collecting work from Ohio and Indiana authors and artists, including William Henry Harrison’s granddaughter, Betty Harrison Eaton, reflecting on life as a Harrison in North Bend. The book did not sell well. His attempts failed, and the forest was logged.

I certainly don’t mourn the man in the tomb who violently swept through the Northwest Territory and lies in rest on top of their dead. However, I do grieve for the long-forgotten poet, Sarah Piatt, who seems to try to atone for her predecessors’ sins, seeking rebirth through the cruel river below.

Sean Andres is a marketer, writer, and educator at non-profit KnowledgeWorks. With Chelsie Hoskins, he operates Queens of Queen City, a public history project lifting the voices of women in the history of the greater Cincinnati area through local schools and publications. He loves to be outdoors among the trees and woodland critters when he’s not glued to the computer — researching, writing, and working.