Langston Hughes

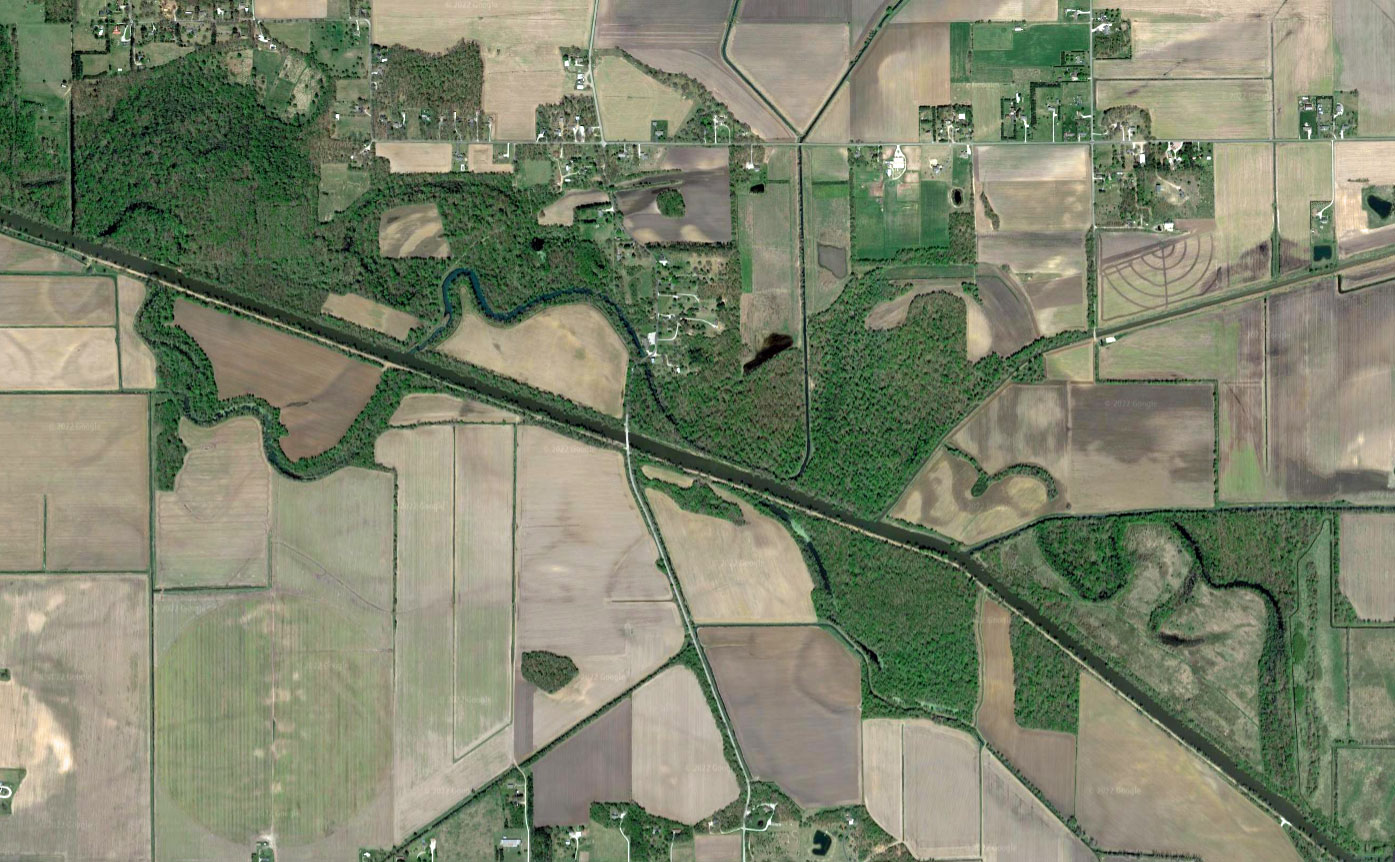

Woodland Park

Lawrence, Kansas

By John Edgar Tidwell

In the weeks leading up to August 19, 1910, all the children in Lawrence, Kansas, were aglow with excitement and energy. To honor the birthday of Editor J. Leeford Brady, the Lawrence Daily Journal set about hosting a Children’s Day party at Woodland Park in East Lawrence. For young Langston Hughes and the other children of color, anticipation turned into anxiety and disappointment when the Daily Journal clarified the meaning of “invitees.” In response to the question about Black children attending, a front-page article confidently asserted: “The Journal knows the colored children have no desire to attend a social event of this kind and that they will not want to go. This is purely a social affair and of course everyone in town knows what that means.”

How could the Black children not want to go?! The Amusement Park would have special vaudeville and picture shows, bands would entertain, a Ferris wheel and a merry-go-round would provide free rides, and such favorites as lemonade and popcorn would be available too. Without knowing it, the Black children had run up against the prohibition made legal by the U.S. Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). The law of the land now defined “social” to mean “forced or unwanted relations.” As protection against undesired interracial interaction, the court endorsed the concept of “separate but equal.” Unfortunately, as Black children in Lawrence and everywhere learned, this legal interpretation granted society permission to practice racial separation without racial equality.

Hughes recreates this incident in Not without Laughter. He deftly enters into the Black children’s high expectations, which rise to a crescendo of excitement, only to be crushed when the admissions attendant refuses to accept the coupons that would admit them to the Ferris wheel, the shoot-the-shoots, and the merry-go-round as well as the entertainment and food. Later, he would capture this feeling of emotional confusion in his poem “Merry-Go-Round.” The speaker in the poem, a little Black girl who had moved from the South to the North, sought to ride the merry-go-round at a carnival. Not knowing if she would be allowed to mount a horse at all, she attempts to find the back of the ride. She laments: “Where is the Jim Crow section / On this merry-go-round / . . .Where is the horse / For a kid that’s black?”

Pernicious racism dogged young Langston Hughes throughout his formative years in Lawrence. To his credit, he never allowed bitterness and hatred to jade his vision of humankind. Instead of blaming all whites for preserving the racial status quo, he learned that “most people are generally good.” This quality, no doubt, inspired the city of Lawrence to begin embracing him as one of its own shining lights.

John Edgar Tidwell is professor emeritus of English at the University of Kansas. He has published six books, including Montage of a Dream: The Art and Life of Langston Hughes, which he co-edited with Cheryl Ragar. Tidwell is currently working with the Dream Documentary Collective and the Lawrence Arts Center to secure funding to make “I, Too, Sing America: Langston Hughes Unfurled,” a documentary film on Hughes’s life and art.

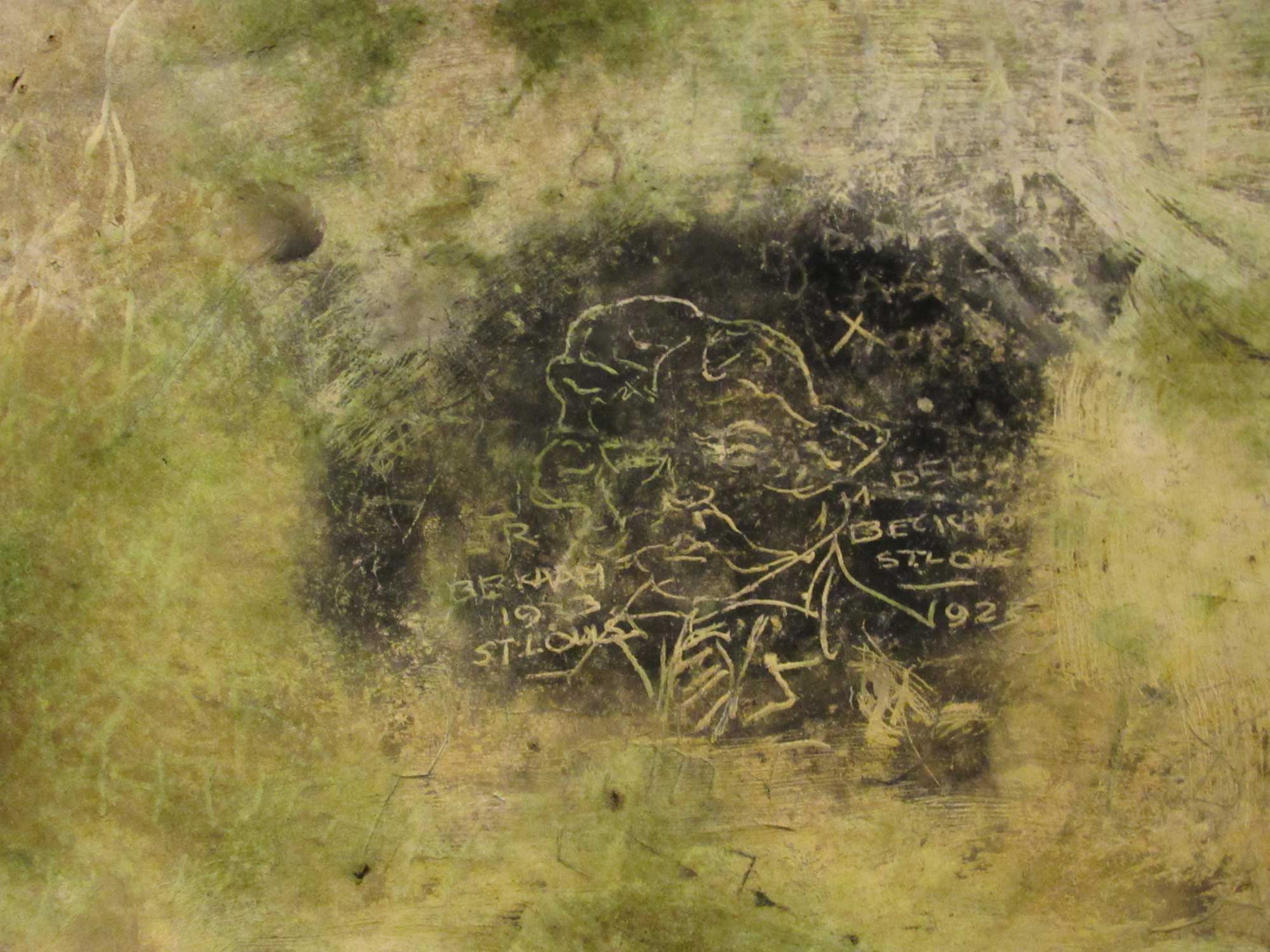

Danielle C. Head, Associate Professor of Photography at Washburn University in Topeka, KS. Head’s photographic work examines the physical remnants of history. Her series “Within and Without” traced the pathways of Lee Harvey Oswald and was selected for inclusion in the Midwest Photographer’s Project at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, IL. Her current work, “The Way Out of Heaven is Of Like Length and Distance” explores the mystique of “The Magic Circle,” a midwestern utopia conceived by economist Roger Babson in the 1940s. Her work can be found at www.daniellechead.com.