TED KOOSER

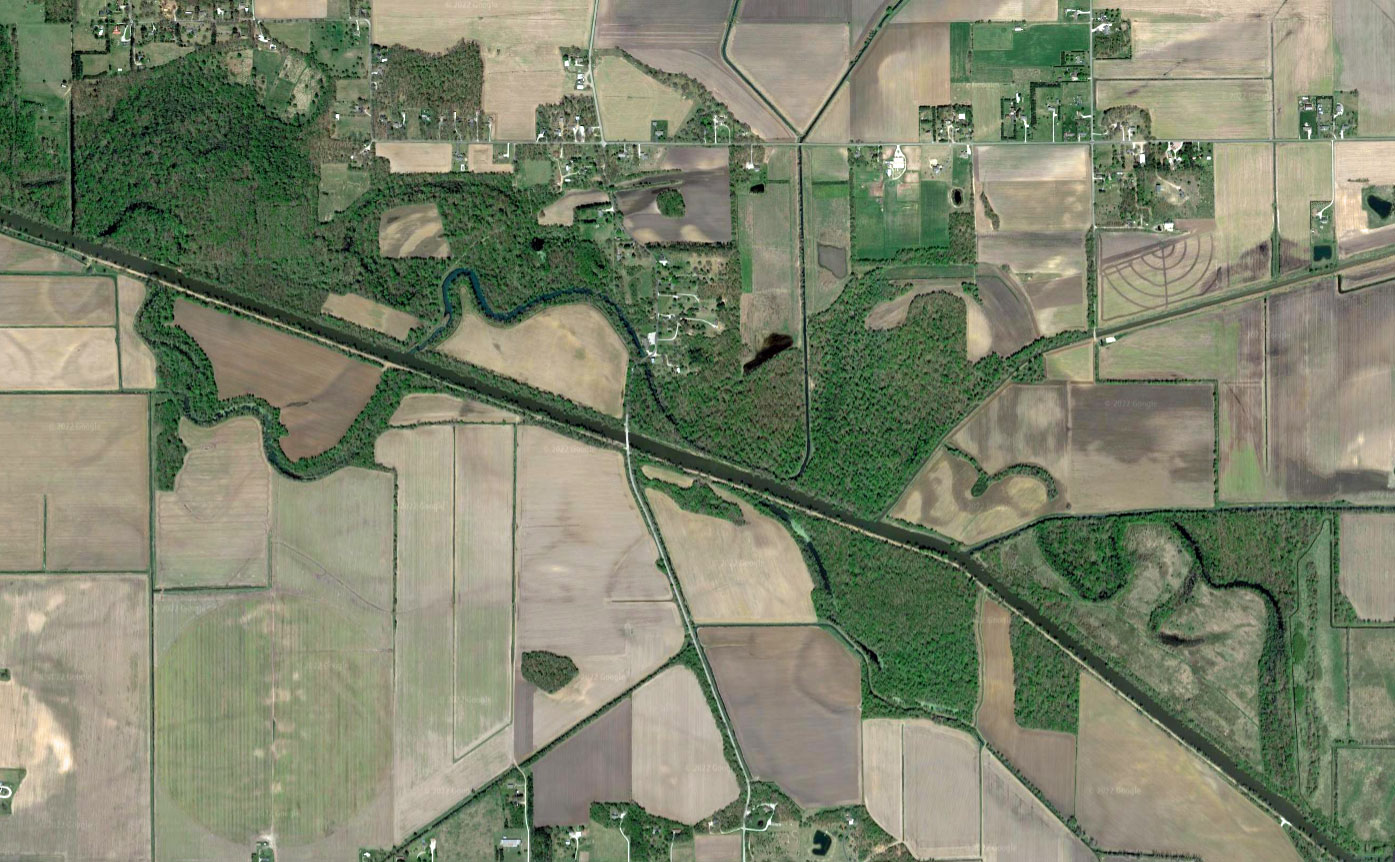

Gravel Roads

Seward County, Nebraska

By Matt Miller

For all his stature as former U.S. Poet Laureate, Ted Kooser remains a poet of Nebraska, and so he is a poet of gravel roads. Consider “So This Is Nebraska,” his best-known poem about his home state:

The gravel road rides with a slow gallop

over the fields, the telephone lines

streaming behind, its billow of dust

full of the sparks of redwing blackbirds.

. . .So this is Nebraska. A Sunday

afternoon; July. Driving along

with your hand out squeezing the air,

a meadowlark waiting on every post.

I grew up in Seward County, just outside of Milford, about 16 miles from Kooser’s home in the village of Garland. Our cars never lacked a thin coat of dust that I found embarrassing any time we went “to town” in Lincoln; the city seemed so clean, with all its white concrete. Still, the gravel roads were our life in Seward County. We met our neighbors there, stopping our cars right in the middle of the lane to chat through open windows. We explored nature and culture on the roads, tossing rocks in Coon Creek or gawking at somebody’s private landfill, posted NO DUPING (exact spelling). Sometimes the roads became our grocery store — we knew where elderberries or wild plums grew in the ditches. Once, we found a stand of edible crabapples and picked gallons of them. As we drove home, we trailed one out the back window of our Chevy Astro with a reel of dental floss, a spot of red leaping on the tan of the washboards.

It is from time spent on those gravel roads that Nebraskans can tell you the shape of our country, that we know where to find the old German church or the local fishing hole. It is because of gravel roads that we know, as Kooser puts it in the voice of a radiator in a broken-down Chevy, “the names of all these / tattered moths and broken grasshoppers / the rest of you’ve forgotten.”

The gravel roads have their limitations as a public square, however. If somebody turns onto your lane, you had better stop gossiping with the neighbor and get out of the way. And Kooser, in his 2002 memoir Local Wonders, highlights another limitation in a rare moment of political commentary. At the start of the book’s consideration of summer in Seward County, Kooser observes “the Fourth of July parade float for this year’s Poison Queen” — two contractors spraying herbicide on the roadside. “While these two hapless men are killing the things they’re paid to be killing,” Kooser laments, “they’re spraying nearly everything else as well: the sunflowers, the pink wild roses, the wild grapevines, the chokecherries.” The public benefit of the gravel roads extends only so far as public willingness to preserve them.

Some of that willingness has grown since Kooser wrote Local Wonders. Now, when I go home, milkweed and yellow signs marking organic crops are commonplace in the ditches. The spraying regimen may have loosened a bit, to judge by the milkweed. And the new prevalence of organic growers testifies to some rising ecological concern, however market-driven. At least some of Kooser’s neighbors in Seward County have understood how these roads and the creatures about them still contour our lives as they do the landscape.

And those contours have lasting meaning. Near the end of Local Wonders, Kooser recounts how the roads helped him endure cancer: “Each day when I came home, I stopped at the head of our lane and picked up a pebble from the road. I lined these up along the kitchen windowsill to count off the treatments” (150).

Mercifully Kooser survived, and so we might imagine that line of pebbles continuing on, day by day, joining up into a road. Beside them on the sill, a wild rose.

Matt Miller now lives outside Reeds Spring, Missouri, where he works with his family to reforest their quasi-suburban lawn with fruit trees. He serves as Assistant Professor of English at College of the Ozarks and writes essays and reviews on ecology, spirituality, and the Midwest. Find him online at matt-miller.org.