Ben Lerner

Topeka High School

Topeka, Kansas

By Molly Hatesohl

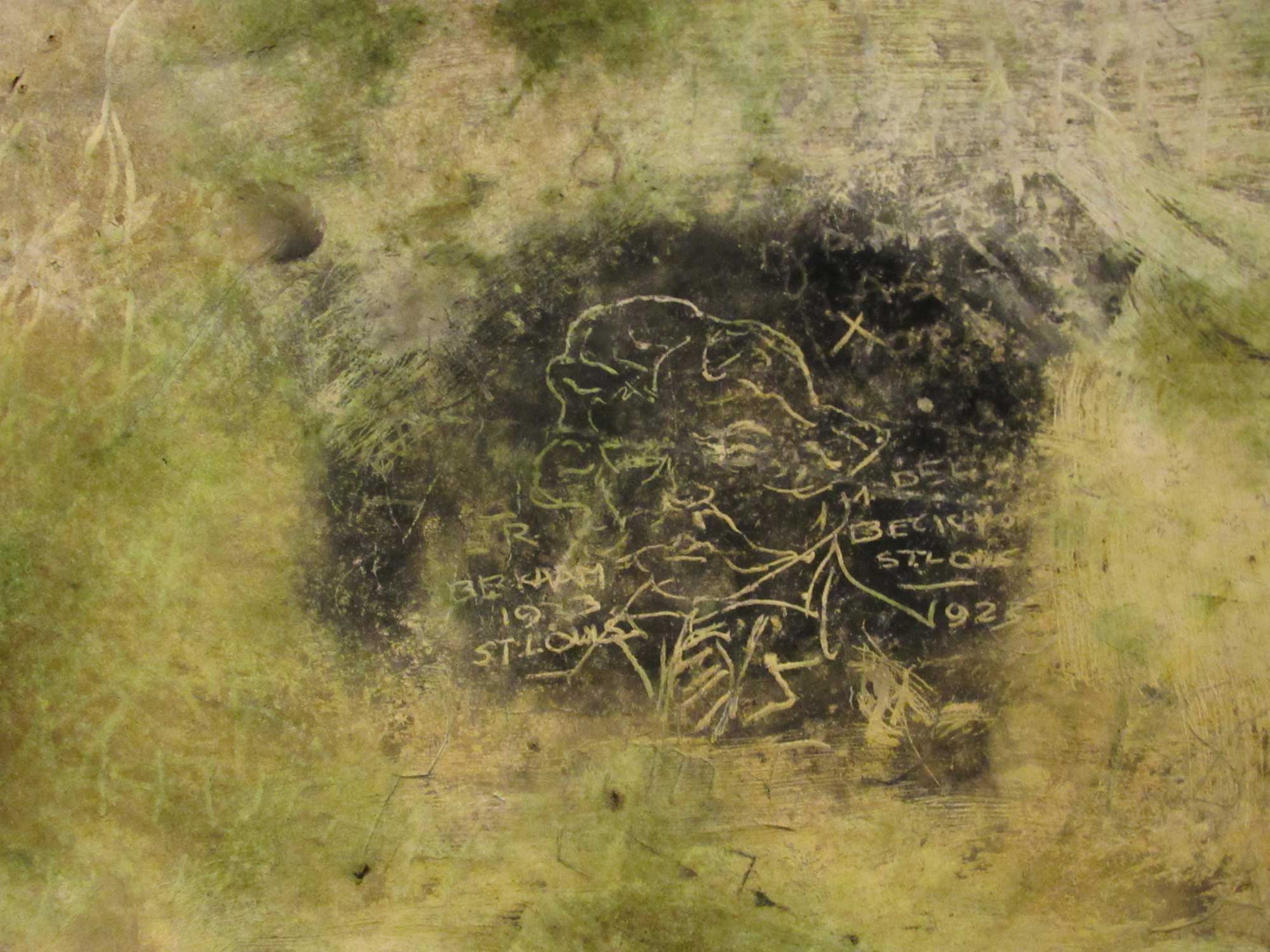

There are many things in Room 103 of Topeka High School that evince its history. Designed in 1930 during the Collegiate Gothic Revival, its granite fireplace and wrought iron chandeliers imbue the classroom with scholastic grandeur. A prodigious display of THS Debate and Forensics memorabilia encircle the room, some photos of former champs more sun-faded than others. But perhaps the most conspicuous artifact hangs high on the back wall, dwarfing the surrounding images: an extra-large portrait of Ben Lerner. Though he is, these days, an accomplished writer teaching at Brooklyn College, this particular photo was taken after he won the 1997 National Speech and Debate Championship.

I first encountered this unsmiling relic in the fall of 2012, when I nervously entered 103 as a sweaty freshman with frazzled hair. As I walked in, the room filled with a sweet, ozonic smell emanating from the huge photocopier in the back corner. It was hard at work, churning out copies of that day’s reading, ripped from the most recent issue of Harper’s Magazine.

Forewarned about the fiery longtime debate coach Pam McComas, I was eager to prove myself.

Wasting no time, Pam gathered the printouts, licked a manicured finger, and tossed stacks of paper at us. The article was titled “A Contest of Words” and was, according to its subhead, an account of high school debate and the demise of public speech written by Ben Lerner. “The individual who wrote this essay,” she said, pointing at the portrait, “is known as the 1997 International Extemp Champion, AKA, my former student.”

I took in the image of the teenager standing over me posing with four giant trophies — straight-faced, oily-haired, and undeniably adolescent. Pam continued, “This will tell you not only everything you need to know about this activity but also how to craft language. In layman’s terms, this is how you beat people up with your words.” I got the sense this was a phrase she had enjoyed using for years.

I gave the text a cursory scan, only kind of understanding Lerner’s elevated prose. His portrait’s eyes stared over my shoulder as I tried to read.

For the next four years, it felt like neither milestone nor mistake could escape Ben Lerner’s scrutinizing gaze. Upon the wall he remained, ever watchful, as I researched the federal budget for transportation infrastructure (the 2012 Debate Resolution). He was there too, when I discovered my parents, who also practiced beating each other up with their words, had received marital counseling from Ben Lerner’s father, a well-known psychologist. I wondered if Dr. Lerner saw something of his son in my father, who was also a competitive high school debater. When, during my sophomore year, Pam confronted me about my apparent lack of motivation, and I confided in her about my parents’ bitter divorce, Ben was, in a way, the only other person in the room. I couldn’t help but feel like Ben Lerner continued to look down on me throughout the tenderest moments of my coming-of-age.

With adulthood, the scopaesthesia diminished. It wasn’t until earlier last year, as I stuffed my life into a U-Haul and relocated from Kansas to Chicago, that I recognized that exacting gaze.

Surrounded by unfamiliar landscapes, and longing for ways to relate to my hometown from a new home, I reached for Lerner’s 2019 novel The Topeka School. Adapted from my first reading assignment in Room 103, Lerner’s novel features a loosely fictionalized version of his high school self named Adam, who, on the cusp of both the National Debate and Forensics Championship and his own manhood, struggles to find his voice amidst the crescendoing chorus of conservative toxic masculinity reportedly endemic to Kansas.

But, what I hoped would reconnect me to the distinctive place I grew up turned out to be something far more disingenuous. Despite its title, The Topeka School is not a book about the unique, history-laden city, nor is it about the multifaceted people who live there. It is, as Lerner has described it, “a book about the prehistory of the bankruptcy of American political discourse.”

Being a prehistory, Lerner’s book assumes an archeological tone of supposed objectivity and encourages readers to do the same. Describing his teenage persona giving practice speeches with a coach, Lerner writes, “Weird to look through the window of the classroom door with the detachment of an anthropologist… and see these two men, if that’s what they are, arguing in an otherwise empty room in a largely empty school.” Suddenly, I was back in Room 103, this time looking down from high upon the back wall, watching my teenage self figure out how to find her voice, utterly incapable of extricating myself from that particular site of our shared history.

Lerner doesn’t write to me, a Topekan, the subject of his study, but to an outsider audience. It’s as if he were a foreign correspondent, reporting back to Brooklynites about trouble brewing on the homefront. In the novel, Adam’s parents worry about how Topeka’s conservative culture might influence their sensitive and intellectual son, whom Lerner characterizes to stand out against this homogenous red state background. Topeka and its high schools serve as a mutable backdrop against which Lerner paints an imaginary Trumpland, the primordial soup that incubated all that’s wrong with America today.

Maybe I would have bought it, had I not grown up in a version of Topeka from which Ben Lerner was impossible to subtract.

This is the problem with casting yourself as the anthropologist of your own culture. In the process of observing specimens, you too are leaving your trace, creating future fossils that others will find and use to construct their own subjective histories. Lerner’s portrait, an important artifact in my memory, was the index of another young person who became himself in the very same place I did.

I don’t wish to pretend that the phenomena Lerner describes in The Topeka School don’t exist. Topeka is full of working parents and latchkey kids, homophobes and misogynists, and white boys with anger issues, sure. So is New York. I also don’t wish to pretend that Lerner or I can be separated from this history simply because we had parents who embraced therapy or because we expatriated to blue state metropolises. Now, having left my hometown, trying again to find my voice, I’m thinking a lot about how we choose to talk about the places where we grew up. I don’t want to pin the decline of civilization on the place that harbored a younger version of me. The land and people I was raised on shaped the person I’m becoming, and I want to honor that. When I write, I want to be integrated with my home, not clash with it.

In an interview promoting The Topeka School, Lerner proclaimed, “Memory lives in places… There are always pockets of the past in the landscape of the present.” He and I are embedded in the history of Topeka, just as a fossil is embedded in the ground. We may not assume the voice of the narrator, nor the anthropologist, lest we forget our own footprints.

Molly Hatesohl is a Topekan living in Chicago.

Photograph by Adam Krohe, a photography student at Topeka High School, Class of 2024.