Jotham Meeker

The California Road

Franklin County, Kansas

By Diana Staresinic-Deane

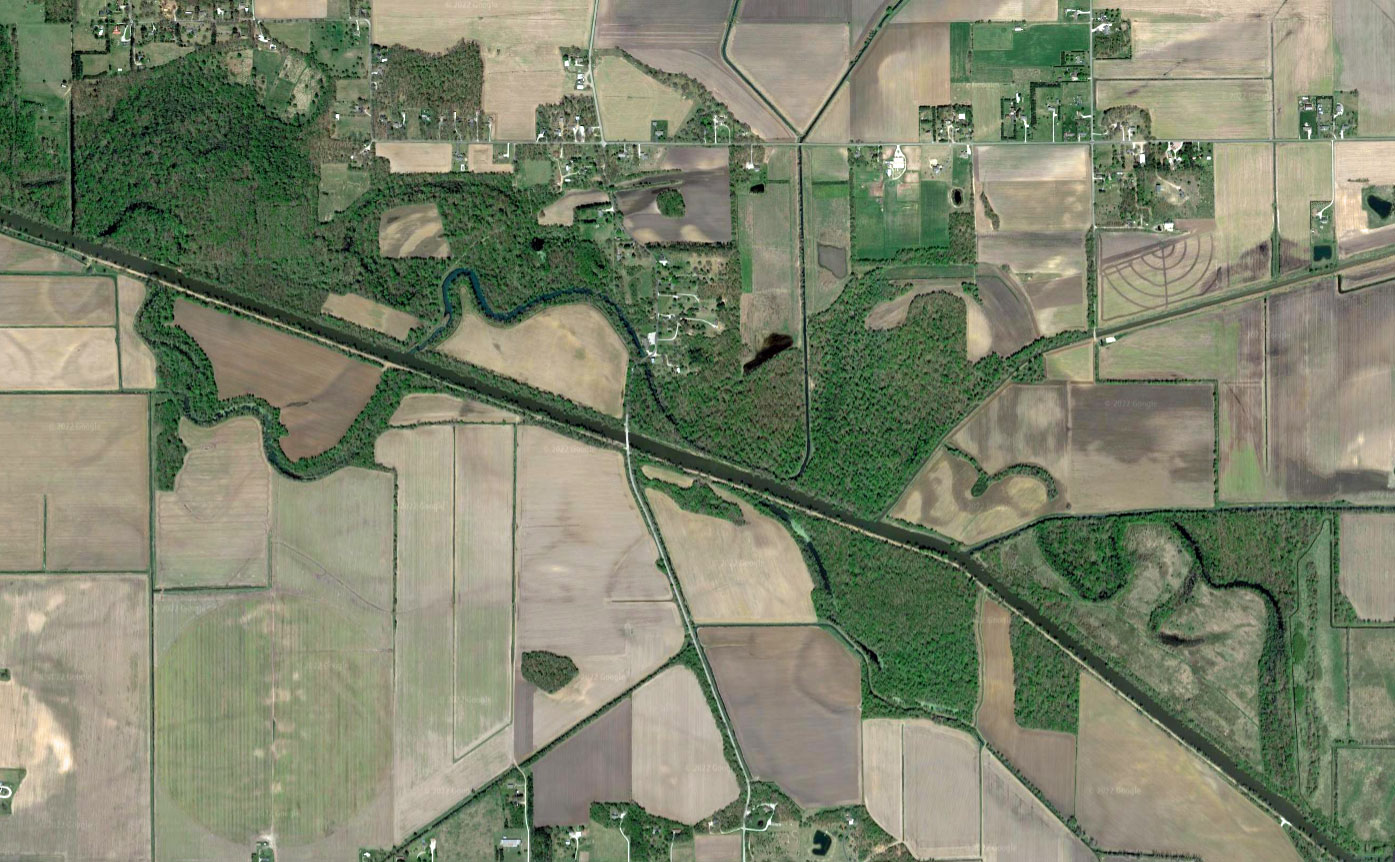

On a rise above Ottawa Creek in Franklin County, Kansas, a shallow depression roughly six feet wide hugs the southern boundary of a battered cemetery before it veers north and vanishes into a fence line. Today it is barely visible, a valley of grass and weeds a slightly different shade of green than the field surrounding it. During the years leading up to Kansas’s statehood, this strip of green was a road that saw hundreds of wagons and thousands of cattle heading west to California and Oregon.

“California emigrants are passing in great numbers,” Reverend Jotham Meeker wrote in his journal from the Ottawa Baptist Mission on April 27, 1852. “Four companies encamped near us last night with 1,300 cattle. On this evening three more companies encamp with 700 cattle. These are exclusive of probably 5 or 600 oxen with 60 or 80 wagons.”

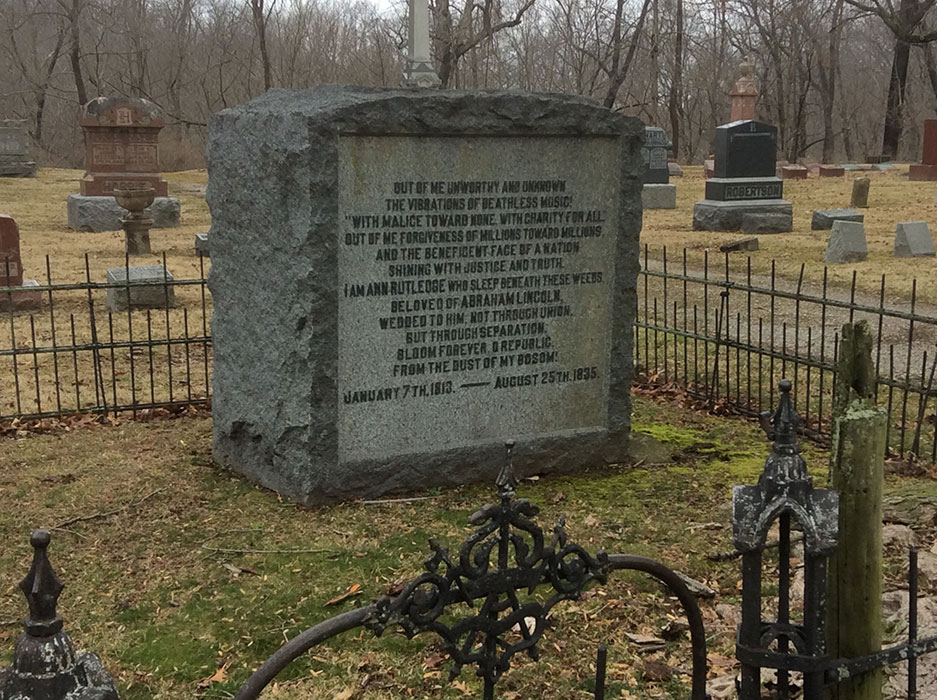

The Ottawa of Blanchard’s Fork and Roche de Boeuf and Oquanoxy’s Village were among several bands of Native Americans forced into present-day Franklin County after losing lands in Michigan, Illinois, and Ohio in the 1830s. More than half of the Ottawa had died by 1837, when Jotham and Elenor Meeker arrived to establish a Baptist mission among them.

Born in 1804, Jotham Meeker trained as a printer before becoming a missionary among the Ottawa, Chippewa, and Potawatomi in Michigan. He became fluent in multiple Indigenous languages, and he developed a phonetic method using Roman type to print in several of them.

When the Indian Removal Act pushed tribes into the Plains, the Meekers were sent there, too. In 1833, at the Shawnee Mission, Meeker set up what is thought to be the first printing press in what would become Kansas Territory. He would print thousands of books and other materials in the Native languages of the various tribes moving to Indian Territory.

In October 1836, Meeker received orders to set up a mission among the Ottawa as soon as a printer could be sent to take his place. By the spring of 1837, construction had begun on the first five-acre mission site, which was situated along the Marais des Cygnes River and the Fort Scott Road. This site was partially destroyed in the flood of 1844 — a flood whose high-water mark was thought to be nearly seven feet higher than the flood that drowned much of Eastern Kansas in 1951.

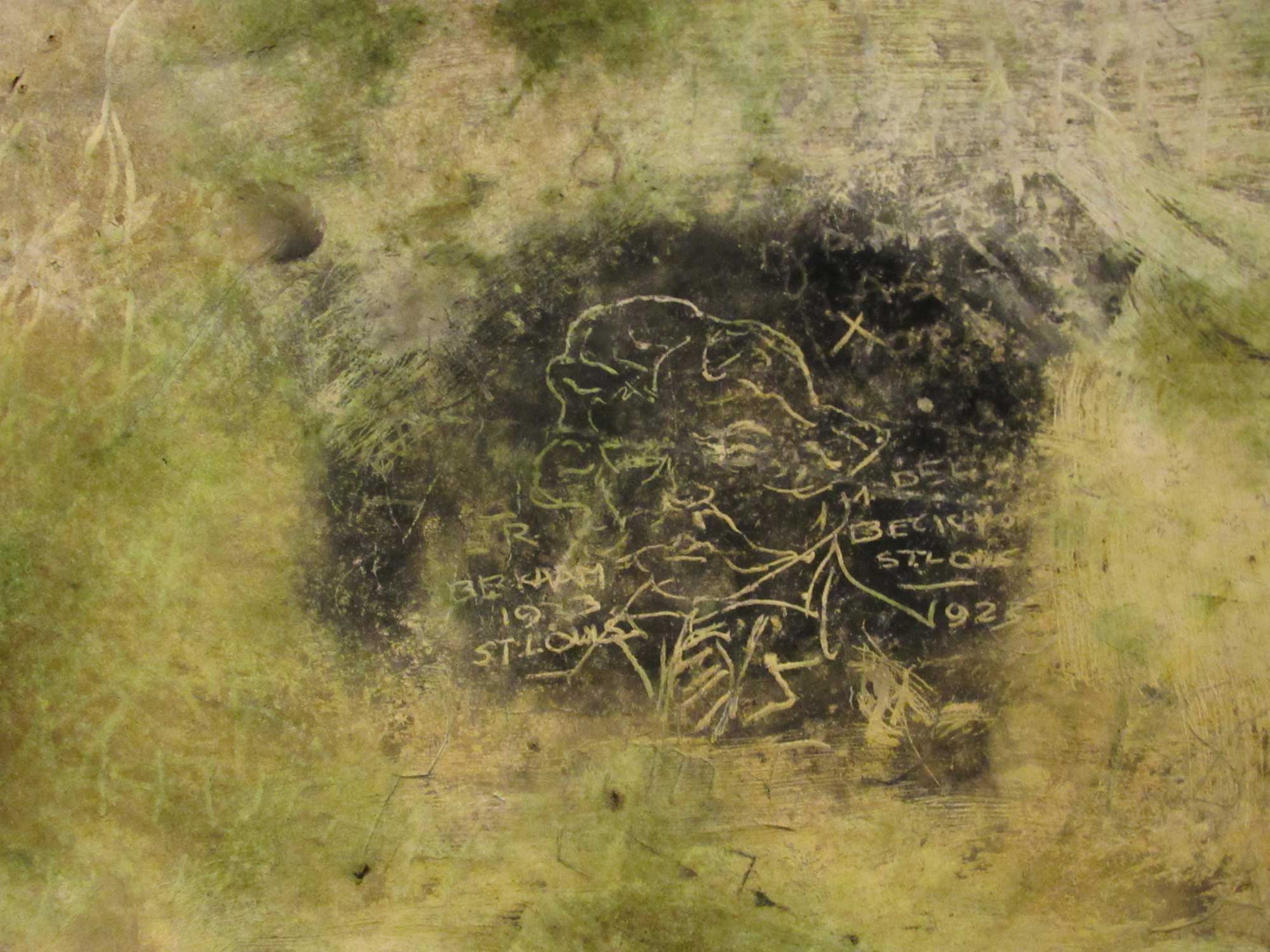

The Meekers rebuilt on higher ground, situating the mission church, cemetery, house, well, and farm on a rise above Ottawa Creek. Although missionaries were undeniably part of the larger colonial machine that devastated Indigenous populations to make way for white settlement, Meeker’s journals and the memories of the Ottawa themselves suggest that the Ottawa and Jotham Meeker had a relatively respectful relationship. Meeker’s journals narrate days filled with visiting families, caring for the sick, and comforting the grieving.

Meeker also documented those traveling along the California Road that passed by the south side of the new mission site. He first mentions the “California emigrants” and a cholera outbreak in 1849. Beginning in 1850, springtime meant hundreds of emigrants passing the mission.

Wagon trails are integral to the history of the American West, and Kansas was often seen as the liminal space that travelers passed through to reach their true destination. Two of those major trails — the Oregon-California Trail and the Santa Fe Trail — passed through Kansas, each traveler on their own journey to somewhere else.

But those trails did not exist in a vacuum; thousands of miles of lesser roads connected the major trails to military forts, Indian agencies, missions, homesteads, water sources, and hunting grounds, and still more roads connected many of those places to each other. Any Kansas road that ultimately linked to the Oregon-California Trail might be called a “California Road,” and one such road carried travelers through present-day Miami County before turning due west into Franklin County and passing through the Ottawa Reserve and Meeker’s Baptist Mission.

“It has now been four weeks since California emigrants commenced passing and we think to this time about 800 wagons and 10,000 cattle have gone along this road,” Meeker wrote in his journal on May 15, 1852. “About 30 wagons and 300 cattle pass to-day.”

Emigrants purchased oats, corn, and potatoes at the mission, but they were less interested in religion, and Meeker wrote that few observed the Sabbath. Emigrants also brought cholera, and on June 15, 1852, Meeker wrote, “California emigrants are returning, fleeing from the cholera. They report that great numbers are dying with it on the Plains. They have two cholera cases with them.” At least one emigrant never left the mission site; the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Gabriel Smith is buried in the cemetery.

The road also brought news and change. On June 1, 1854, Meeker noted that, “Nebraska and Kansas Territories are organized,” referring to the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which passed just two days earlier. He also wrote of emigrants who “are squatting around us in great numbers,” signaling the beginning of white settlement in Kansas Territory and what would soon be the end of Indian Reserves in Franklin County.

Jotham Meeker died January 12, 1855, leaving behind hundreds of pages of journals documenting life with the Ottawa in Kansas before it was Kansas. His wife Elenor died in 1856 and is buried in the mission cemetery next to Jotham. The mission fell into ruin, though the cemetery would continue to be used by both the Ottawa and white settlers. Shortly after the Civil War, the Ottawa were forced to sell their lands in Kansas and move to Oklahoma.

The California Road, which was drawn into the official government land survey maps created between 1856 and 1864, was no longer an official road by the time Leonard F. Shaw and G.D. Stinebaugh published their map of Franklin County in 1878. Later travelers followed section line roads, and later still, Kansas Highway 68 and Interstate 35. Although these roads allow for faster and safer travel, they can’t offer the intimate knowledge of a road that hugs the curves of the land, climbing hills, splashing into creeks, and passing through thousands of acres of wildflowers at the pace of a wagon train.

I am fascinated by old trails, and I am forever searching for remnants of paths that once connected us to other people and places. Where we are is shaped by our ability to get there, and I have spent many hours standing in the depressions that still remain, thinking about the people and goods and animals who once followed that path in their journey.

Today at the old mission site and cemetery, a steady Kansas wind carries the sounds of faraway travelers: the drone of high-speed traffic on I-35 and K-68, the buzz of a small plane, the horn from a distant train, chatty bluebirds and nuthatches hopping from perch to perch in the trees. The only stillness is in the old California Road itself. Yet, as I stand in the swale of this former road, I can imagine a time when the Meekers and the Ottawa could hear lowing cattle and creaking wagons hours before they reached the mission on their way to somewhere else.

Diana Staresinic-Deane grew up in Kansas City, Kansas, and currently calls Ottawa, Kansas, home. She is the executive director of the Franklin County Historical Society in Ottawa and a member of the Humanities Kansas Speakers Bureau. She is the author of the book, Shadow on the Hill: The True Story of a 1925 Kansas Murder. Diana can often be found exploring old cemeteries and searching for remnants of historic trails.

Read Jotham Meeker’s journals at the Kansas Historical Society, or visit their archive for a more complete Meeker collection.