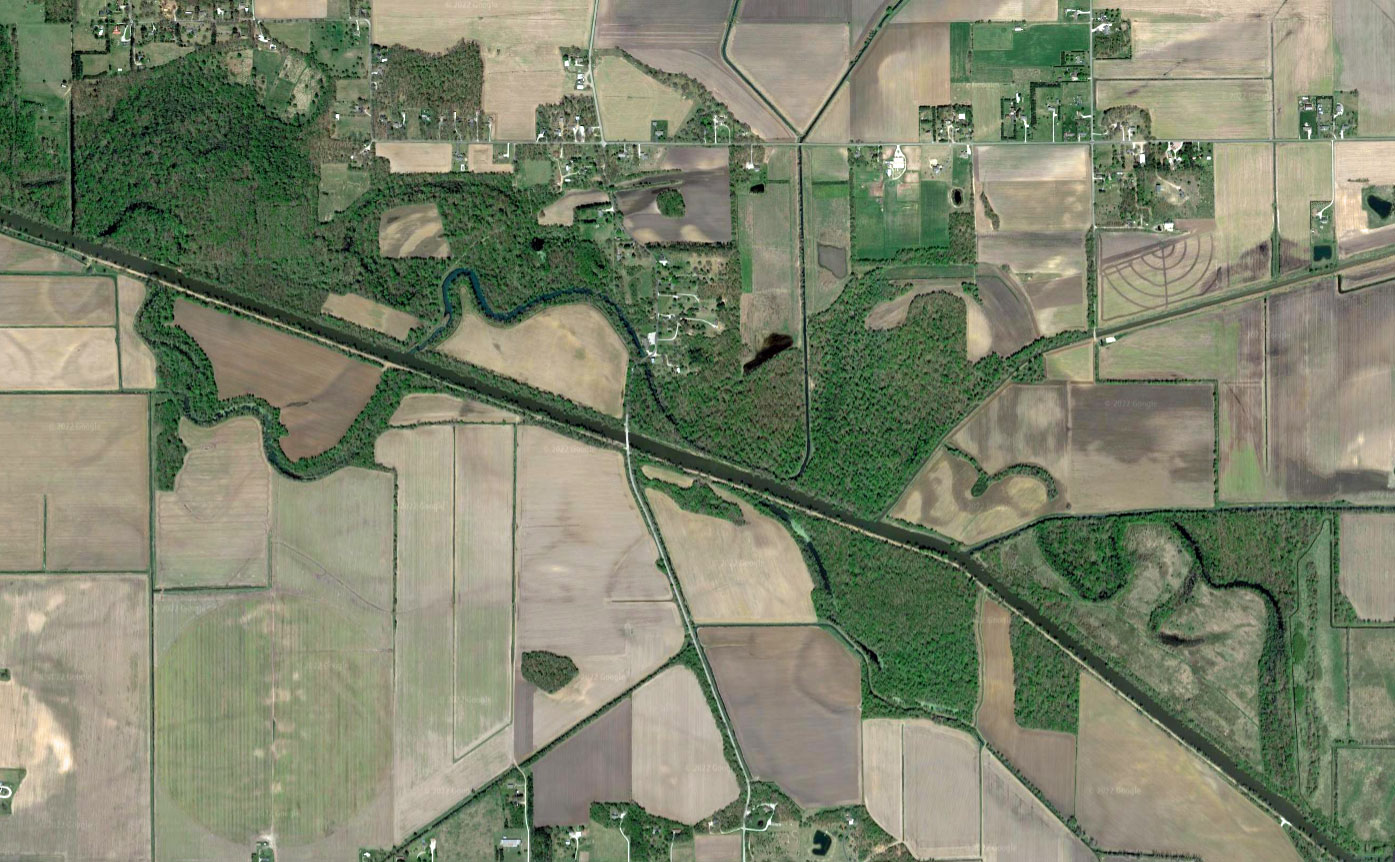

Nellie Maxey

Edwards County Historical Museum and Sod House

Kinsley, Kansas

By Joan Weaver

Starting in Washington, D.C., you can drive U.S. Highway 50 all the way to San Francisco. Along the way is the small Kansas town of Kinsley with a towering sign that announces you are “Midway” across the continent. Contrary to being just the “midway” of a journey, Kinsley has been the desired destination for many people. Some came on the Santa Fe Trail, others on the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railroad, or, more recently, like I did, on a modern highway.

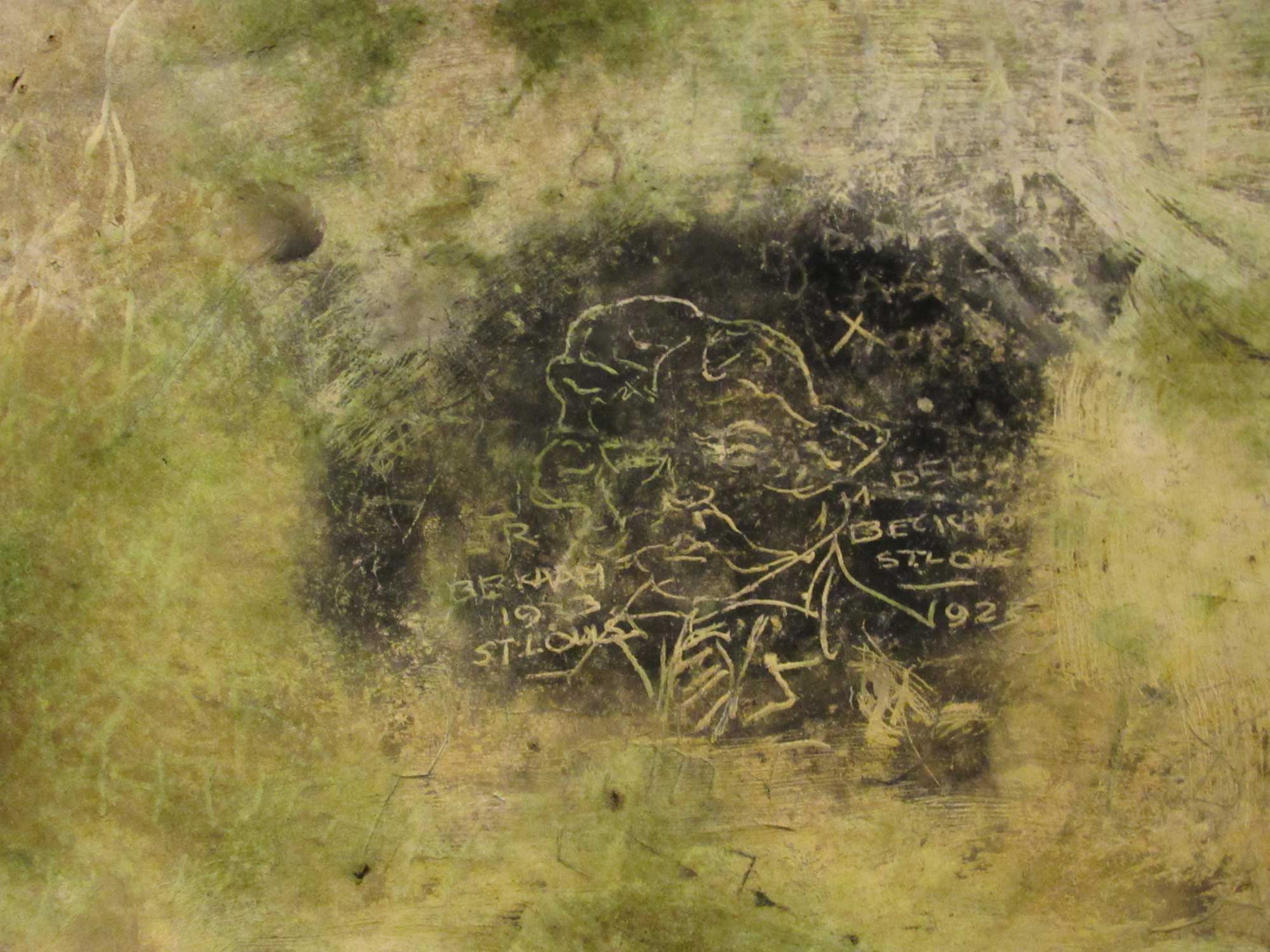

The sign also invites you to visit the Edwards County Historical Society Museum to see how the pioneers lived on the prairie. You can go inside a reproduced sod house built in 1958 by men who still remembered the process. On exhibit are the tools they used and pictures taken during construction. The house contains period furniture and artifacts donated by the descendants of the early settlers. Because the original open-air sod house required continual upkeep, in 2001 the Edwards County Historical Society preserved the house by building a structure to encase it.

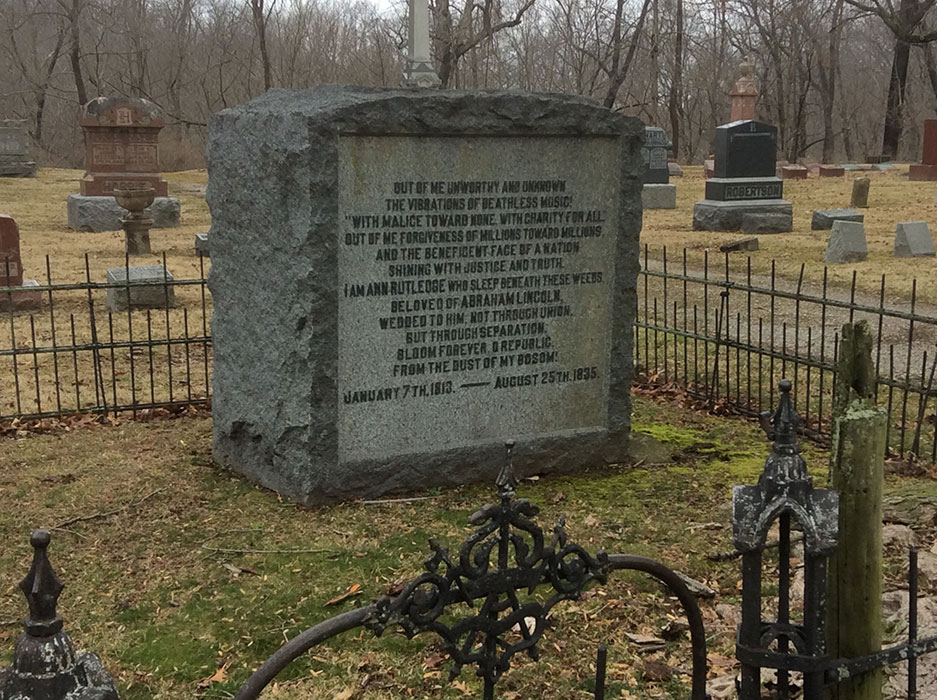

Among the early immigrants were the Maxey family from Galesburg, Illinois. On October 1, 1886, George and Clara Maxey gathered their six children into a covered wagon pulled by two horses to begin the 650-mile trip to Kinsley. Penelope “Nellie” Maxey was twelve and very excited and a little frightened. The day before, some mean boys had jerked on her braids and told her that Indians would scalp her.

“Our wagon was very well built and warm,” recalled Nellie in an interview celebrating Kinsley’s 1973 centennial. “Father had it built wide over the wheels so beds could be arranged sideways and that is where we slept. And don’t forget to mention my dog Bounce. He trailed the wagon, walking all the way from Illinois.”

Despite his wife’s warnings to not be swindled, in Missouri George traded their faithful horse for a mule “with more endurance.” It was a long, hard trip, and the family arrived at Clara’s brother-in-law’s brickyard on November 7. “We slept in a tent that first night we were in Kinsley and nearly froze,” Nellie remembered.

The following day, they headed nine miles south to homestead next to Clara’s sister. Remembering her mother’s warning, Nellie said, “When we got halfway there, the mule, Jack, laid down and died. Father walked to my aunt’s place and brought back a horse to team with the other to take us on our way.”

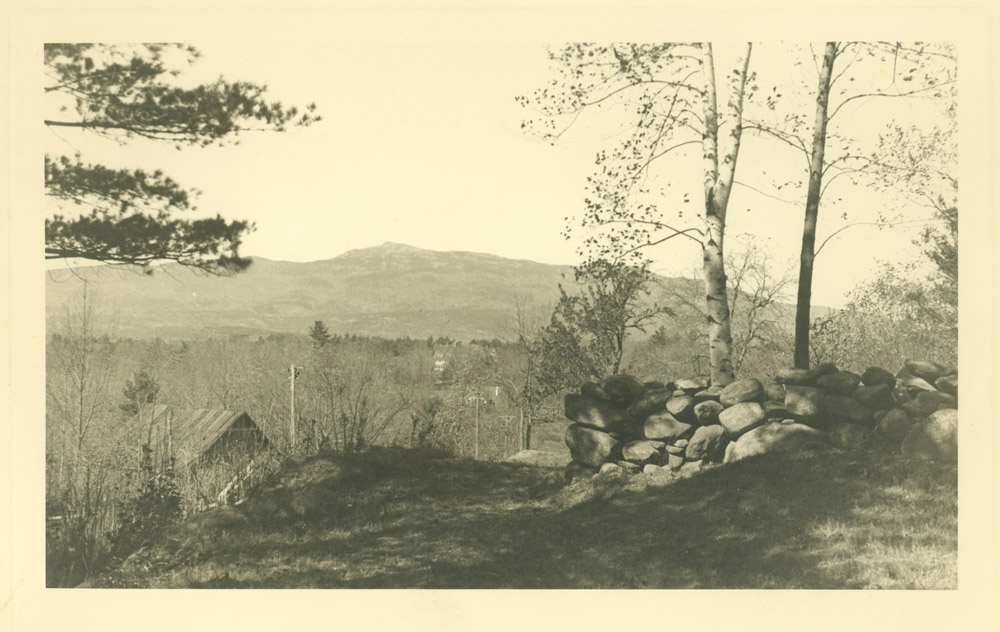

The Homestead Act of 1862 offered “free” land to settlers if they would build a house, make improvements, and farm the land for five years. The Maxey’s claim was ancient sand dunes covered with short buffalo grass and a few thorny plum bushes – no tree in sight. Regular prairie fires and grazing buffalo herds eliminated trees in the prairie ecosystem.

In this area, building with sod was the quickest, most inexpensive way for settlers to improve their claims. Sod blocks should not be confused with the dried adobe bricks of the Southwest. With sod, thick buffalo grass roots held the soil together, and blocks could be cut and lifted intact. Typically, blocks were 24 inches long, 12 inches wide, and four inches deep. They weighed 50 pounds each, and it took 3000 blocks to build a 16-foot by 20-foot house.

There are no pictures of the Maxey house, but a family of eight would have needed shelter quickly. The sod would have been broken with a plow, cut into blocks and stacked. For some families, red clay from the banks of the nearby Arkansas River was mixed with sand and used as mortar. After this mortar dried, it became almost as hard and durable as cement. The same mixture could also be used to stucco the inside and outside of the house.

Sod homes often were topped with rafters covered with tarpaper and a thinner layer of sod, grass side up. Sometimes boards were laid loosely, covered with several layers of asphalt roofing and left exposed.

Living in a soddy had some advantages. The insulating, two-foot-thick walls offered coolness in summer and warmth in winter, aided by burning buffalo chips. However, housewives found many disadvantages. Bugs, mice, and snakes, including rattlers, liked to move in. Dirt floors were hard to keep clean. Heavy rains eroded walls and leaked through the roof, leaving wet furniture and muddy floors.

After the Maxeys settled in, Nellie learned there was no need to fear Native people. The U.S. government had called for the eradication of the buffalo in order to defeat the Plains tribes who resisted the takeover of their lands by white settlers — including the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Apache, and Comanche. No buffalo meant no food and no Indians.

The next summer’s real threat came from hot winds and drought. The sun beat down every day. Their corn crop withered despite all efforts to carry buckets of water from the well to every stalk. The land was lonely and harsh, threatened by grasshoppers, rattlesnakes, hail-storms, and occasional cyclones and prairie fires. At night, Nellie would lay in bed listening to coyotes howling.

One hundred years later, in 1989, I too found myself moving to the sandhills. I was luckier than the Maxeys, as we purchased an existing six-room, one-bath frame farmhouse built by homesteaders in 1907.

Our moving train consisted of a U-Haul truck, two cars, two pickups, and three trailers hauling our riding horse, two miniature horses and a1959 Ford tractor with implements. The dog rode in the car with our two teenaged sons.

Our entourage took one long day to move 500 miles at a top speed of 50 mph. Compared to the Maxeys, my hardships were minor. I broke a finger loading the horse into the trailer. We arrived after dark to find the barn full of eighty years of detritus. When I put the riding horse into the corral, four-foot weeds obscured my view of an open back gate. She escaped into the dark. Fortunately, the pasture fence was intact, and she appeared back at the barn in the morning, covered in biting flies. When I applied fly repellent, it must have stung, because she reacted by landing a good back-kick on my knee. All I could do was crawl out of the corral, driving sharp sandburs into my shins. Less than 24 hours in Kansas, and I was ready to leave.

In time, life became more manageable for both Nellie and me. She would marry a lawyer and live in a large Victorian house as one of Kinsley’s leading ladies until her death at age 85 in 1959. After thirty-five years, I still live in the old farmhouse, which has since been remodeled with a large master bedroom and bath.

Now, I go to the sod house museum to discover stories like Nellie’s. The names on the donated artifacts I see there are familiar surnames of my friends who are their descendants. I spend time talking to those friends and researching in the old newspapers and the library archive. I suppose I’m a little like the sod house museum, as I too want to preserve and share the stories of the early people who settled midway across the continent.

Joan Weaver has been the director of the Kinsley Public Library for twenty-seven years. She has a passion for discovering, preserving, and making the stories of her adopted prairie community digitally accessible. Currently she is working on a book about Kinsley’s role as the regional center for culture and the arts in the early twentieth century.

Photo by Bob Obee.