John Bartlow Martin

Smith Lake Camp

Herman, MI

By Ray E. Boomhower

Writing about the Upper Peninsula of Michigan in his classic regional history Call It North Country (1944), John Bartlow Martin described the expanse as “a wild and comparative Scandinavian tract—20,000 square miles of howling wilderness on the shores of Lake Superior.” Like numerous fishermen, hunters, and hikers before him, Martin was attracted to the UP by its “magnificent waterfalls, great forests, high rough hills, long stretches of uninhabited country, abundant fish and game.”

From his introduction to the region in the summer of 1940, selecting it as a suitably remote site for a honeymoon, to Martin’s death in 1987, the reporter, freelance writer, diplomat, and Democratic presidential speechwriter found himself drawn, again and again, by the UP’s quirky charms. As he warned would-be tourists: “You will have to do nearly everything for yourself. The region is not geared to make your visit painless.” The lack of modern conveniences and the clannishness of the locals could be maddening, he pointed out in Call It North Country (tattered, well-thumbed copies of which can still be found on bookshelves in many UP cabins), but if an outsider adjusted his thinking and fit into the region’s ways, he could find “no better vacation spot.”

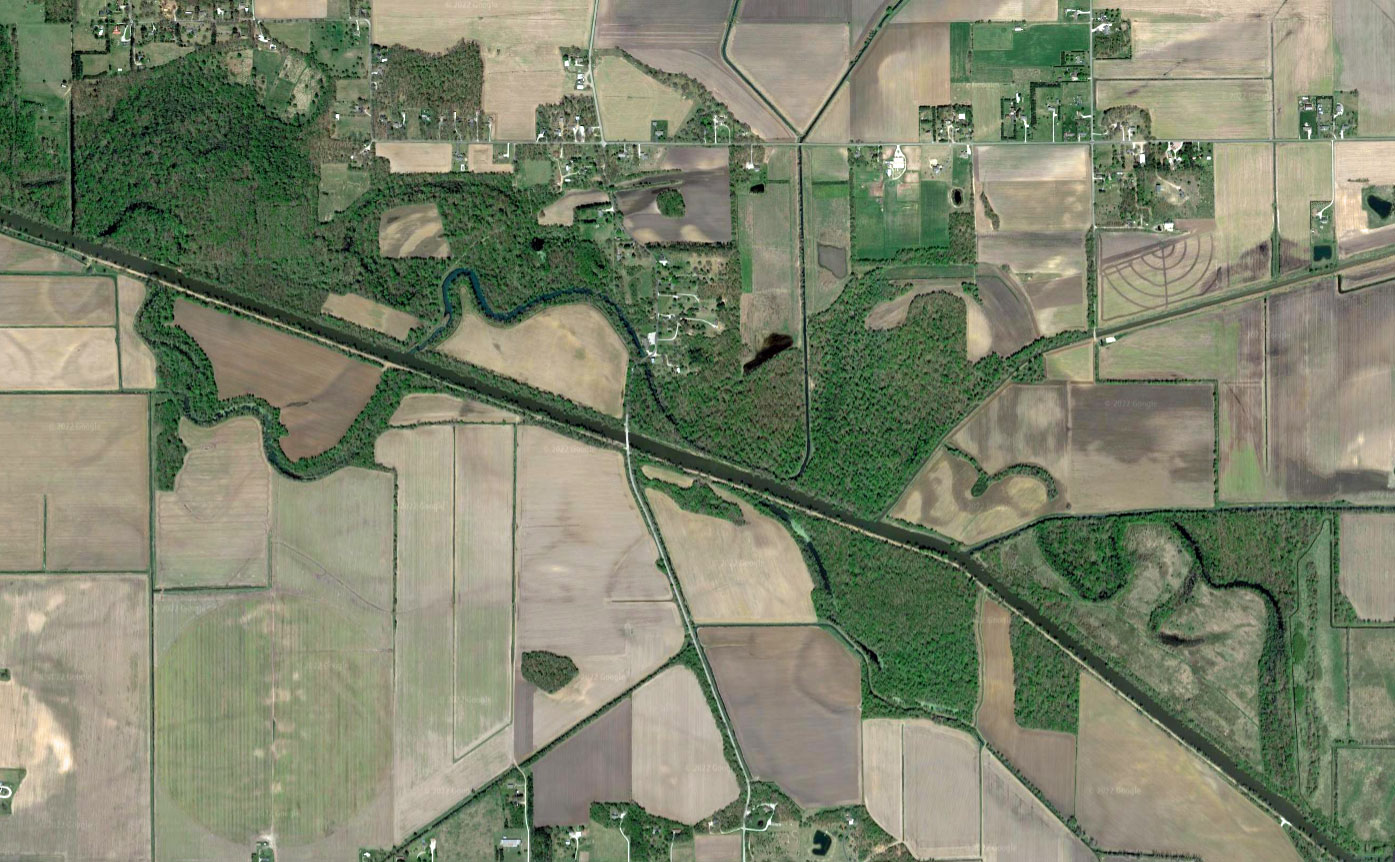

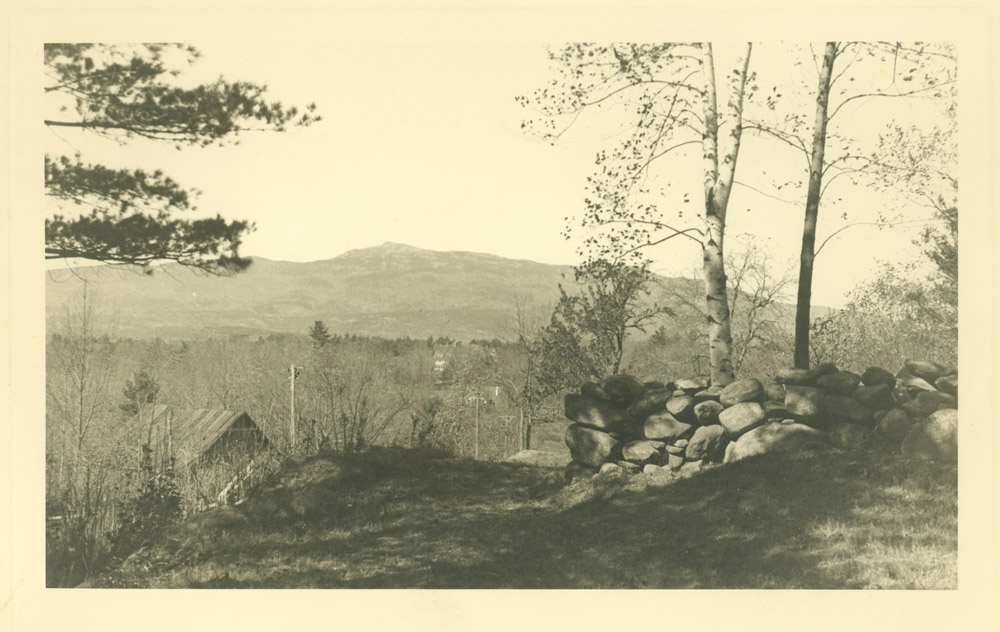

The UP, however, became more than just a regular tourist stop for Martin. In January 1964 Martin and his wife, Fran, purchased a 180-acre site outside of Herman, Michigan. Not far from the water’s edge on their property they discovered the ruins of an old trapper’s shack, which they used as a temporary shelter. They constructed a camp (as cabins are known in the region) on top of a high, granite cliff sixty feet above the lake. Enormous white pines towered over the hemlocks located on the cliff, sheltering and shading the cabin.

Martin oversaw the construction by Finnish carpenters of a thirty-foot by thirty-foot log cabin with a large living room, kitchen, bedroom, indoor bathroom, and an enormous fireplace built out of fifty tons of native rock. As Martin’s son Dan noted, his father and mother loved “the wildlife, the remoteness, the sense that they were in touch with nature.” His family remembered that Martin did not believe in cutting down trees or their branches on his land, even if they interfered with the view of the lake from the cabin. “If you want to see the lake,” Martin insisted, “go get in the boat and see it.”

During his family’s summer stays Martin fished, tried his hand at carpentry, did some writing, and relaxed in a sauna that later featured the front page of the New York Times announcing the resignation from the presidency of his longtime political foil Richard Nixon. “No television, no telephone, once a week to town for mail,” he said of his routine. The cabin also became a sanctuary for Martin, a place where he could retreat to when tragedy, as it often did in the 1960s, struck, as when his friend Robert F. Kennedy fell to an assassin’s bullet in June 1968. At night, Martin, when troubled, could look up and see the Milky Way, appearing like “a white river,” with every star “blazing” as he witnessed “man’s satellites slowly tracking across the firmament.”

I decided while working on a biography of Martin that I needed to visit his Upper Peninsula retreat to get a better sense of what this wild place had meant to him. Martin’s daughter, Cindy Coleman, graciously offered to show me the cabin on a visit I made in September 2013, just before it was shuttered for the upcoming winter. I knew I was in the Upper Peninsula when, upon stepping out of the truck to open a gate so we could proceed along a rugged former logging road to the cabin, a large black fly saw its opportunity and delivered a vicious bite to the back of my neck. The spot still hurt when we passed a small, wooden sign with white letters affixed to a tree near the road that read: “J. B. Martin / Smith Lake.”

Reaching the end of the road, I could barely make out Martin’s cabin, nestled as it was among the trees. Although I did not stay long enough to hear coyotes howling in the night as Martin had done, I sat on the screen porch attached to the cabin, enjoying its dark-wood floor, sturdy beams, and simple, rustic furnishings. Relaxing in one of the wooden chairs, I was stunned, at first, to see that, with Martin’s death, there now was a clear view to the lake through the trees. Watching the waves from the porch as the wind rustled the branches of the nearby trees, I reflected that Martin had made all the right choices when it came to his cabin’s location, but maybe, just maybe, had been wrong about the lake view.

Ray E. Boomhower is a senior editor at the Indiana Historical Society Press. He is also the author of more than a dozen books, including Richard Tregaskis: Reporting under Fire from Guadalcanal to Vietnam, John Bartlow Martin: A Voice for the Underdog, and Robert F. Kennedy and the 1968 Indiana Primary. His next book is about Malcolm Browne, Associated Press Saigon bureau chief in the early 1960s, and his famous photographs of the burning monk.