Rachel

Fort Crawford

Prairie du Chien, WI

By Christy Clark-Pujara

On November 4, 1834, a twenty-year-old “mulatto” woman named Rachel filed a freedom suit in St. Louis, Missouri. She claimed that a military officer named Thomas Stockton held her in slavery at Fort Snelling for two years and then moved her to Fort Crawford in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. According to Rachel’s suit, Thomas “took your petitioner to … Prairie du Chien for about two years, holding your petitioner as a slave … causing her to work for & serve him & family at that place during that time as a slave at which place her child James Henry was born.” Rachel argued that her residence and her son’s birth in the free territories made them free people. Slavery was prohibited by federal law in the Northwest Territories. But, despite the ban on slaveholding, Black Americans were held in bondage; in fact, federal military officers were given an allowance to cover the cost of hiring a servant or keeping a slave.

Rachel had been extremely vulnerable at Fort Crawford. She lived in a space dominated by armed white men, and she was regarded as property. Moreover, because Fort Crawford was under construction, Rachel was burdened with serving Thomas’s family, which included two infants (born in 1831 and 1832), in extremely crude conditions. Life on the Midwestern frontier became even more taxing when Rachel became pregnant and gave birth to a boy named James Henry, whose father is not revealed in the historical record. Rachel was not protected by status or race or law or family. She had no legal or social recourse against the sexual advances of the multitude of men who had access to her, especially Thomas. And, in 1834, just months after she gave birth, Thomas took them to St. Louis and sold them to Joseph Klunk, who sold them to William Walker — a local slave trader.

Somehow, Rachel and Henry escaped and made their way to the courthouse. Rachel petitioned for legal representation: “your petitioner prays that your petitioner and said child may be allowed to sue as a poor person in St. Louis Circuit Court for freedom & that the said Walker may be restrained from carrying her or said child out of the Jurisdiction of the St. Louis Circuit Court till the termination of said suit.” Her petition was granted, but Rachel lost the case. The circuit court ruled that slavery was not prohibited in the Territories when enslaved people were put to work serving military officers. Rachel appealed, and in June of 1836, the Missouri Supreme Court overturned the lower court’s decision. They asserted that Thomas had violated the ban on slaveholding in the Northwest Territories when he purchased Rachel from the slaveholding state of Missouri after he was stationed at Fort Snelling. Rachel’s courage and audacity are palpable, seen especially in her use of a legal system created to disempower her.

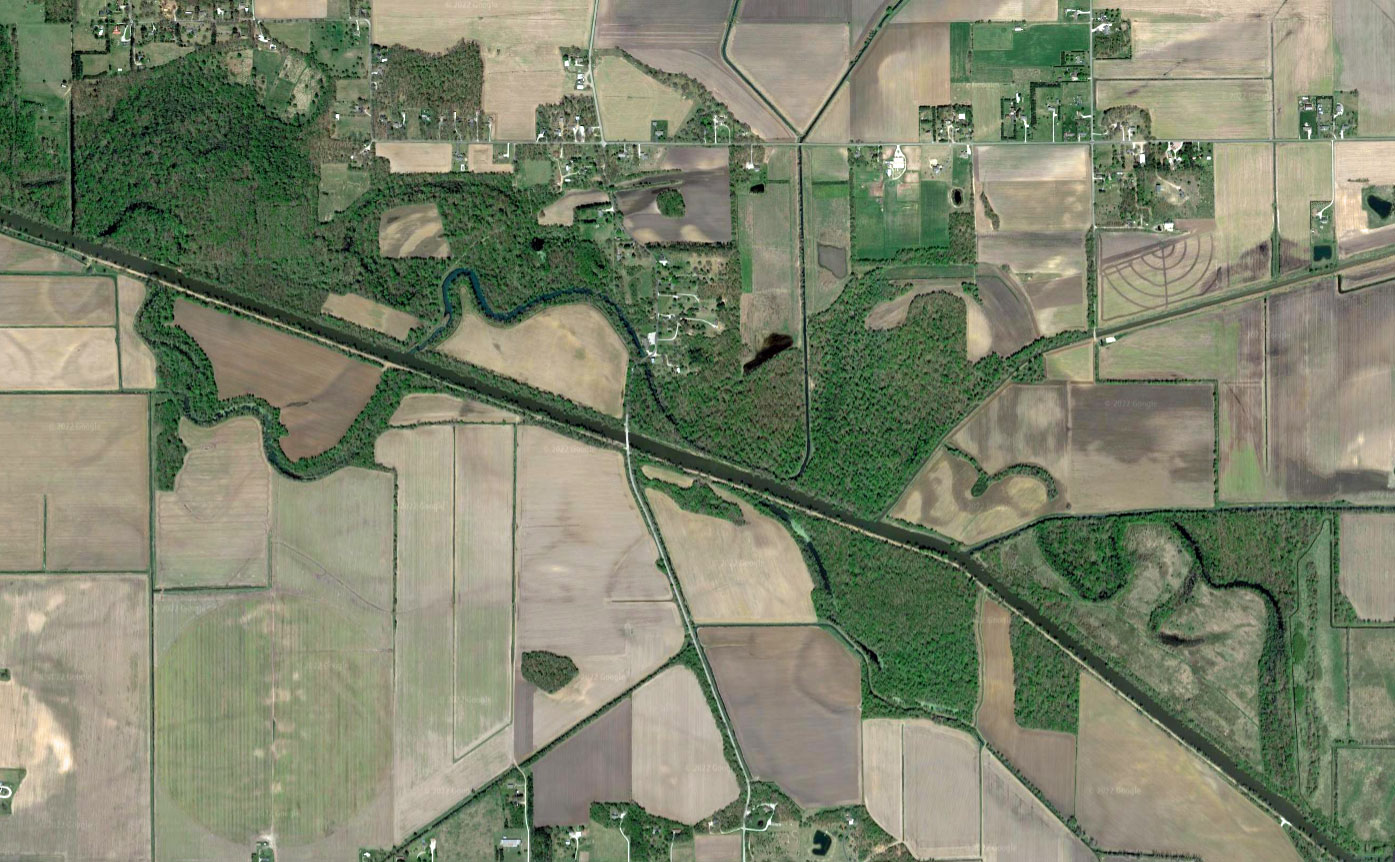

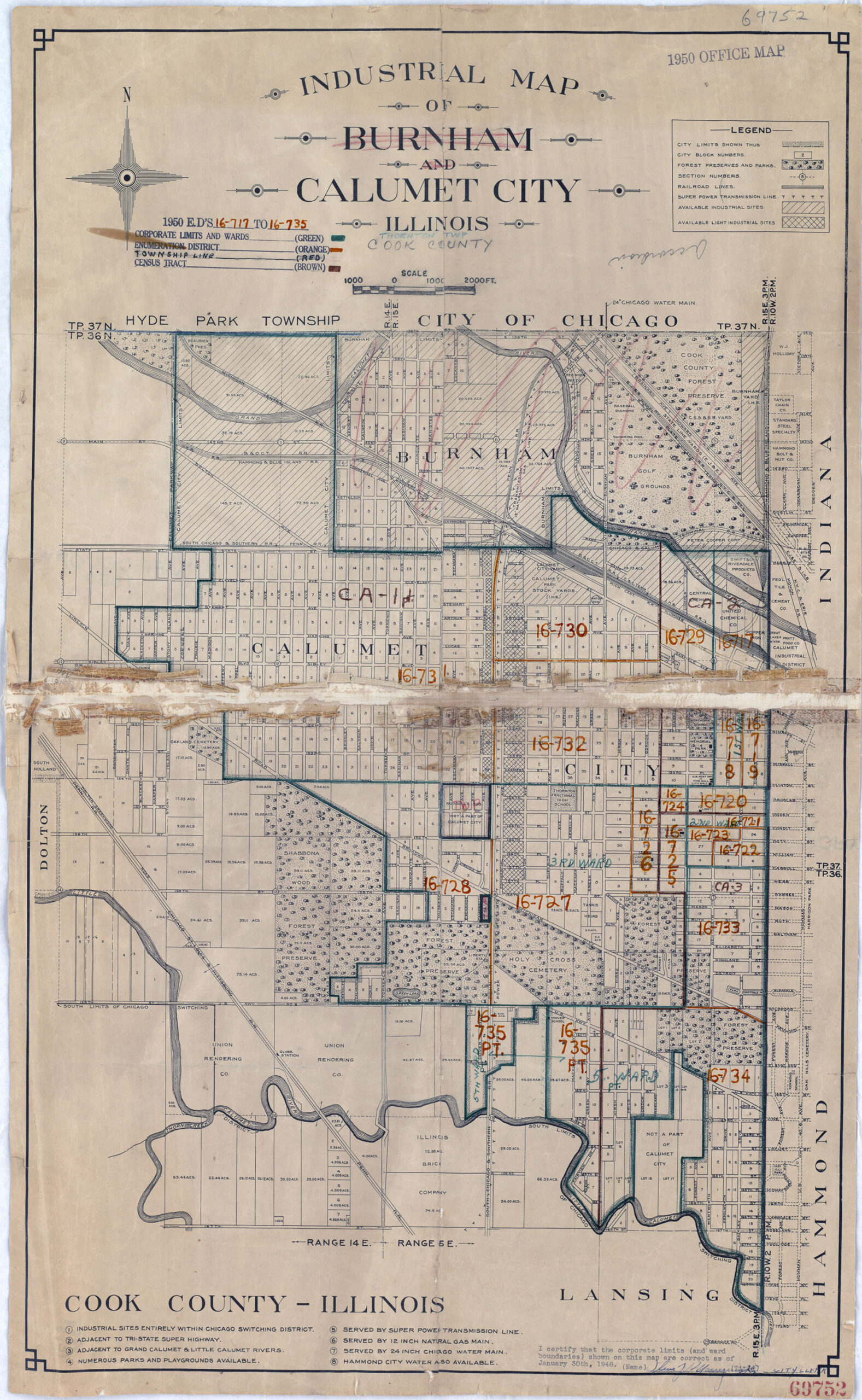

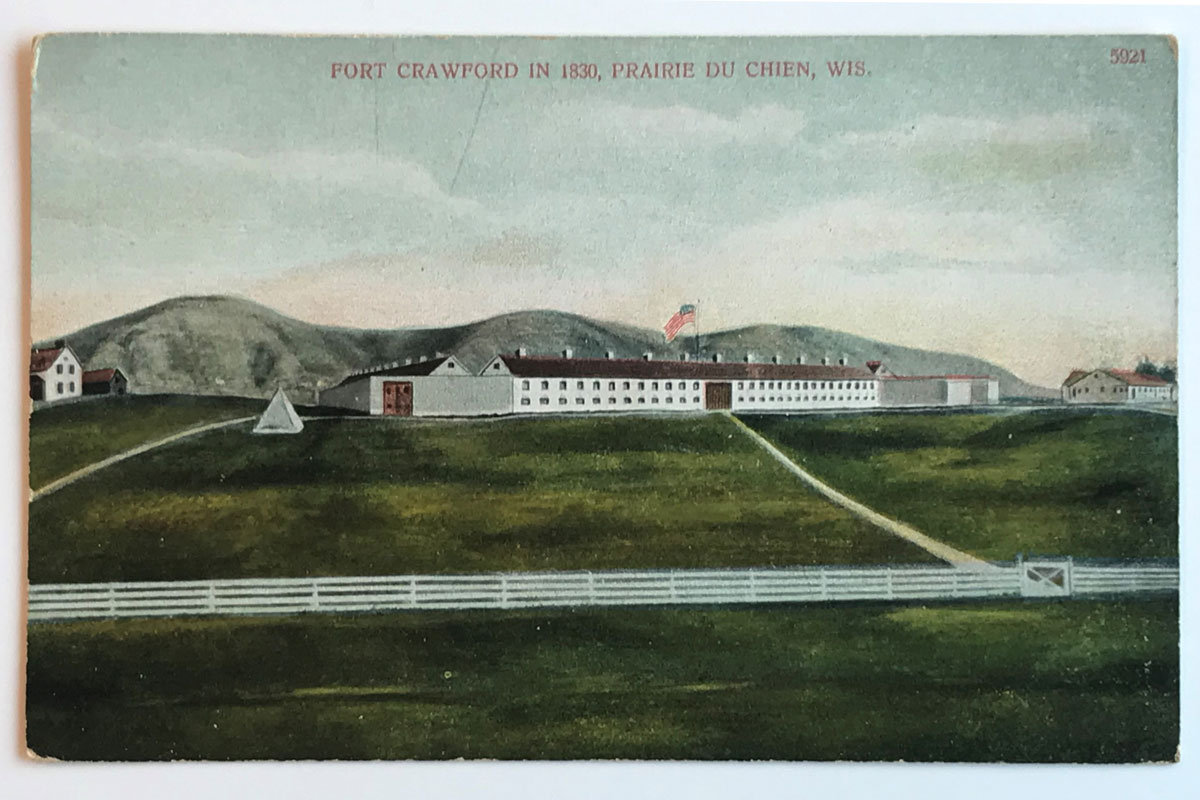

I first visited Fort Crawford two years after I accepted a faculty position as a historian in the Department of African American Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. I knew enslaved people were held at forts throughout the Midwest, but I did not associate Midwestern frontier forts with the larger institution of race-based slavery in the United States. Mainly, I understood these frontier forts as part of American westward expansion and empire building that violently and viciously displaced Indigenous peoples. The area around Prairie du Chien, where the Mississippi River meets the Wisconsin River, has been home to Indigenous peoples for over 12,000 years, most recently the Meskwaki, Sauk, Ho-Chunk, and Dakota peoples who had been repeatedly forced off their ancestral lands. Prairie du Chien had been a center of French fur trading since the 1680s, the oldest European settlement on the Upper Mississippi River. Both the French and British claimed territory in the region. Fort Crawford, founded in 1816, would come to represent American hegemony in the region. Built from local oak timber, it formed a square of 340 feet on each side. In 1826, the fort was severely damaged by a flood. In 1829, construction began on a new elevated fort made of limestone, which was completed in 1834.

Rachel was brought to this contested space. She was enslaved in the hinterlands of the American empire, and she bore witness to the daily realities of the displacement and violence of “manifest destiny.” She literally witnessed the physical building of the American empire in the “West,” and she was forced to contribute to that process in service of Thomas, his wife, and his children. At least seventeen African Americans were held in race-based bondage in and around Fort Crawford between 1820 and 1845. Slaveholding at Fort Crawford, like forts throughout the Midwestern frontier, was a part of the expansion of race-based slavery in America. And slaveholding officers served to undermine the ban on slaveholding and permit its practice in the region. Race-based slaveholding was so embedded in white American culture that its practice persisted even when it was explicitly and legally banned. As a life-long Black Midwesterner whose maternal family settled in Nebraska before it was a state and a historian of American slavery, I was astounded about how little I knew or had even considered knowing about race-based slavery in the Midwest.

Midwestern frontier forts, like Fort Crawford, are places that illuminate and expand understandings of American slavery and Black people’s tenacious pursuits of freedom. People like Rachel are part of a larger history of slaveholding in the United States. Stories like hers transform how we experienced these places. For me, these forts have become archives, places to contemplate Black history and experience. And while I am frustrated that stories of people like Rachel have only recently — and often marginally — been included in the historic presentation at these sites, I am inspired when I imagine that maybe I have walked where Rachel walked, maybe touched a wall she watched being built. My current book project Black on the Midwestern Frontier: Contested Bondage and Black Freedom in Wisconsin, 1725–1868 seeks to tell the stories of people like Rachel and expand how we understand American slavery, the social-cultural formation of the Midwest, and Black people’s pursuits of freedom and liberty.

Christy Clark-Pujara is a Professor of History in the Department of African American Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. She is the author of Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island (NYU Press), and her research focuses on the experiences of Black people in small towns and cities in northern and Midwestern colonies and states in British and French North America before the Civil War. Her current book project, Black on the Midwestern Frontier: Contested Freedoms, 1725–1868, examines how the practice of race-based slavery, Black settlement, and debates over abolition and Black rights shaped race relations in the Midwest.

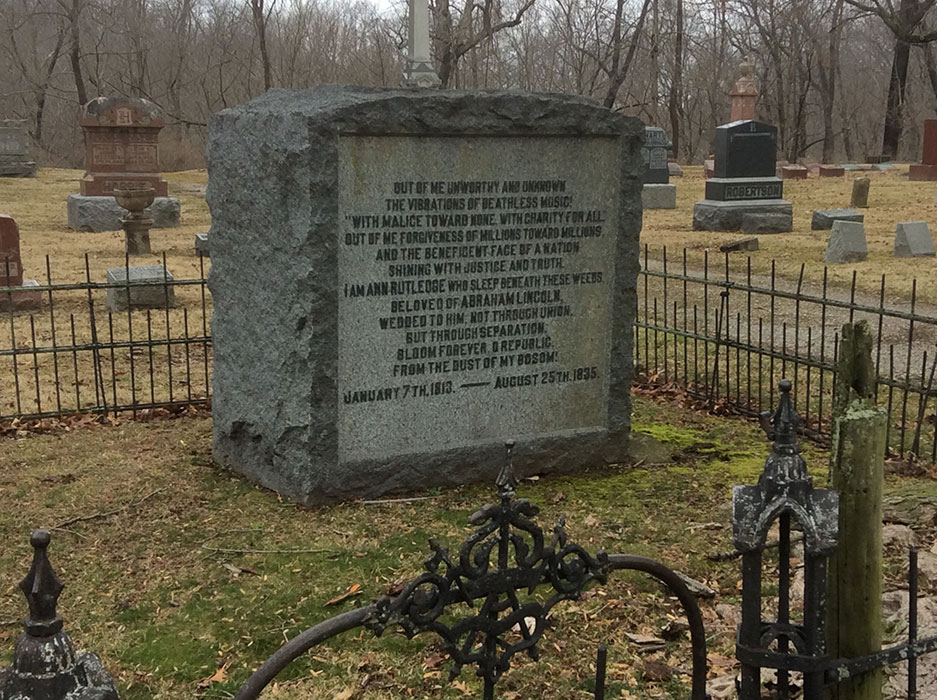

Rachel’s petition and other documents related to Rachel v. William Walker (1834) can be found on the Digital Gateway of the Washington University in St. Louis.

The image is a detail from a painting by A. Brower, circa 1840, that was reproduced on a 1908 postcard published by A.C. Bosselman & Co.

![Twain in study window 1903 Mark Twain in Study Window [1903]](https://newterritorymag.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Twain-in-study-window-1903.jpg)