Richard Wright

4831 S. Vincennes Ave.

Chicago, Illinois

By Joseph S. Pete

Powell’s Books used to have a few locations in Chicago, none anywhere near as large as the fabled city block full of books in Portland. Now only its venerable Hyde Park bookstore remains, but I fondly remember the Lincoln Park Powell’s with its distinguished rows of dark-wood bookshelves soaring up to the ceiling, the rarefied upper shelves reachable only by sliding ladder. It had the hallowed airs of some centuries-old university library. It’s where, as a pock-faced and perpetually despondent teenager, I first obtained a copy of Richard Wright’s Native Son, which swiftly became one of my favorite and most re-read books.

Fran Lebowitz said at a recent talk at the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago that literature should be a window and not a mirror. I found Wright’s Native Son to be both. It was a mirror in that I hailed from the heavily industrialized and culturally similar Northwest Indiana just outside the familiar South Side landscapes he described. As a troubled youth, I could also relate strongly to Bigger Thomas’s alienation and desperate sense of doomed hopelessness. And Mary Dalton’s rebellious dalliance with communism spoke to my burgeoning political consciousness. I was delving deeper and deeper into reading serious literature and Native Son had more recognizable touchstones than the 19th-century British and Russian classics I was devouring around that time. It just clicked for me.

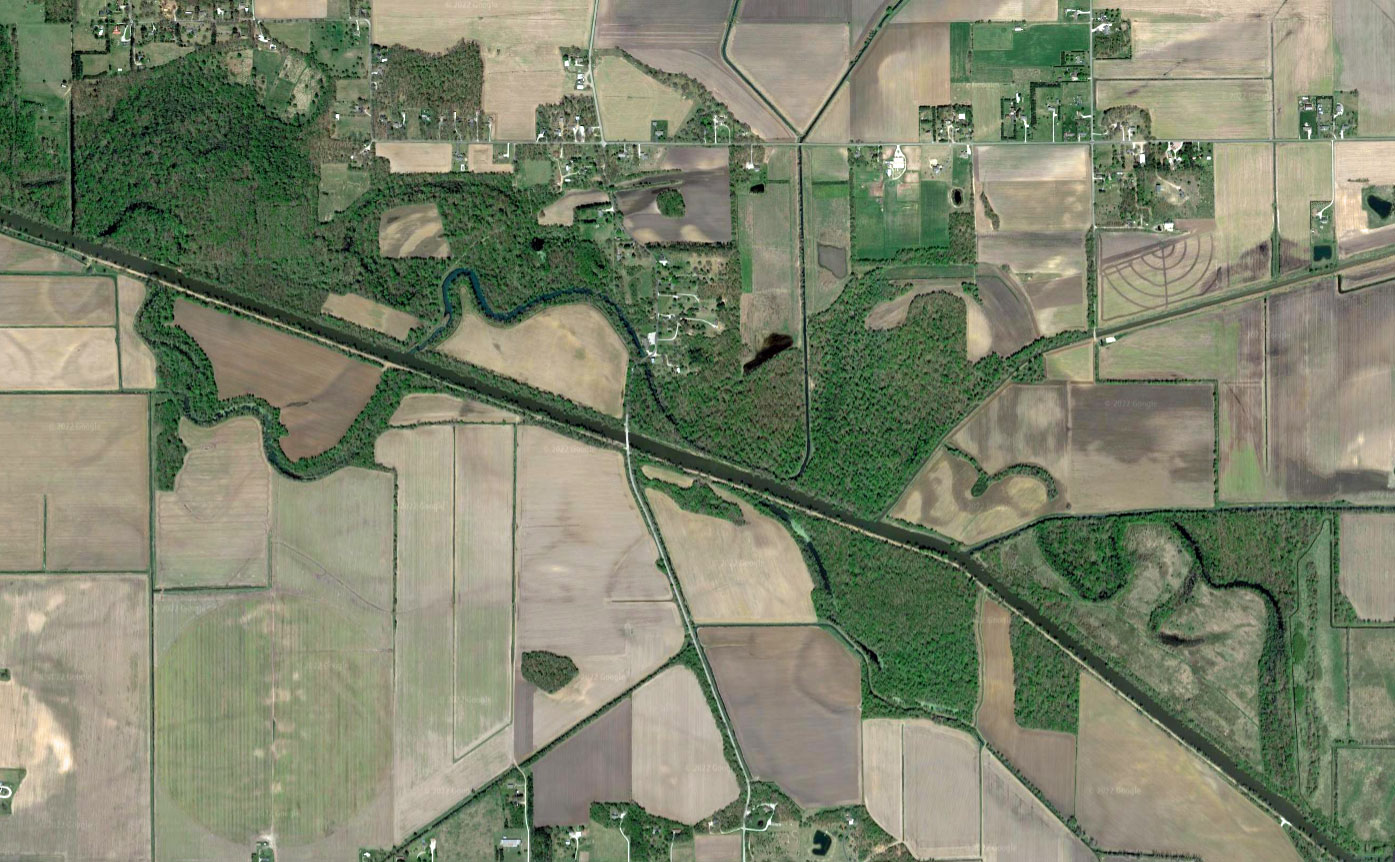

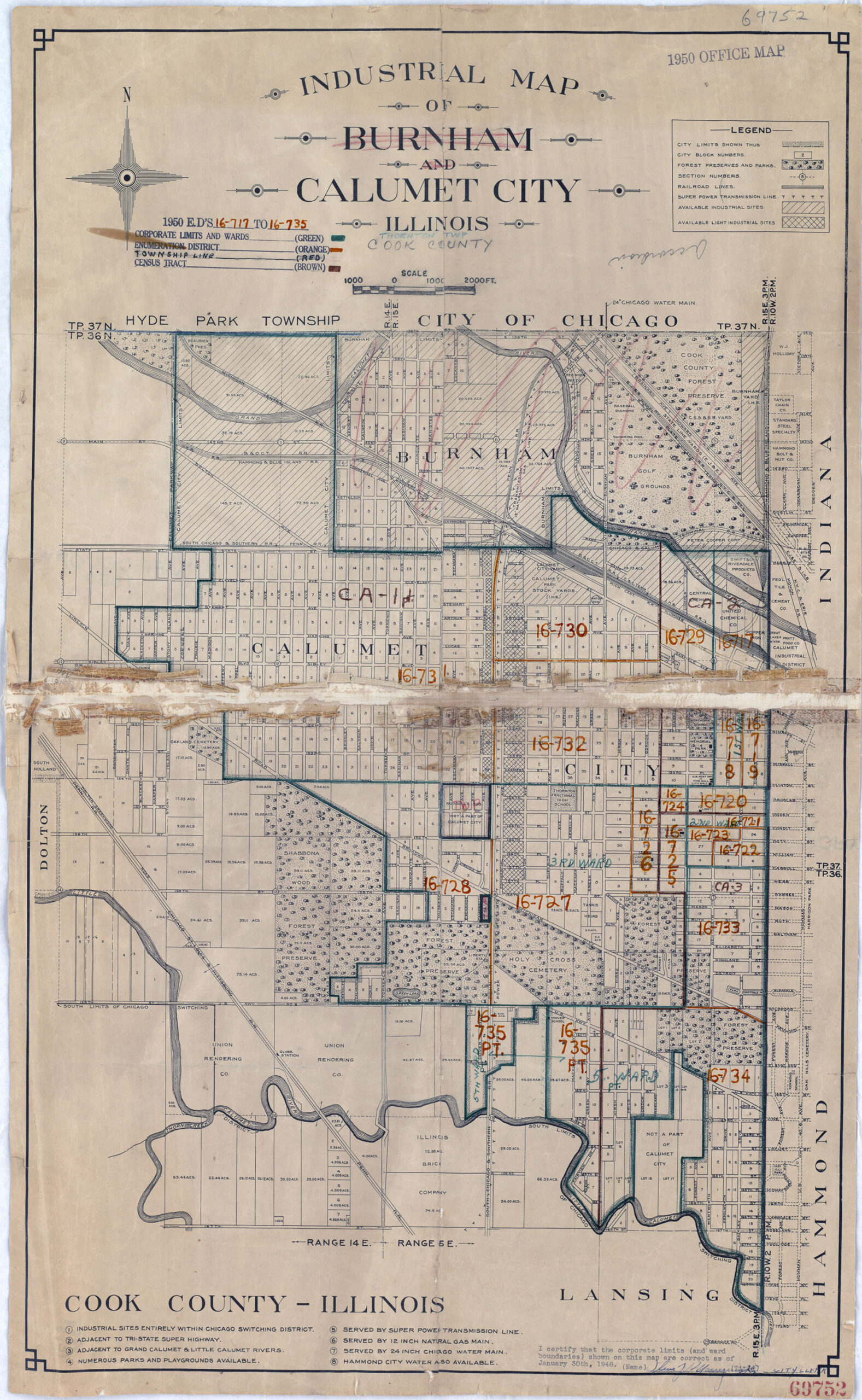

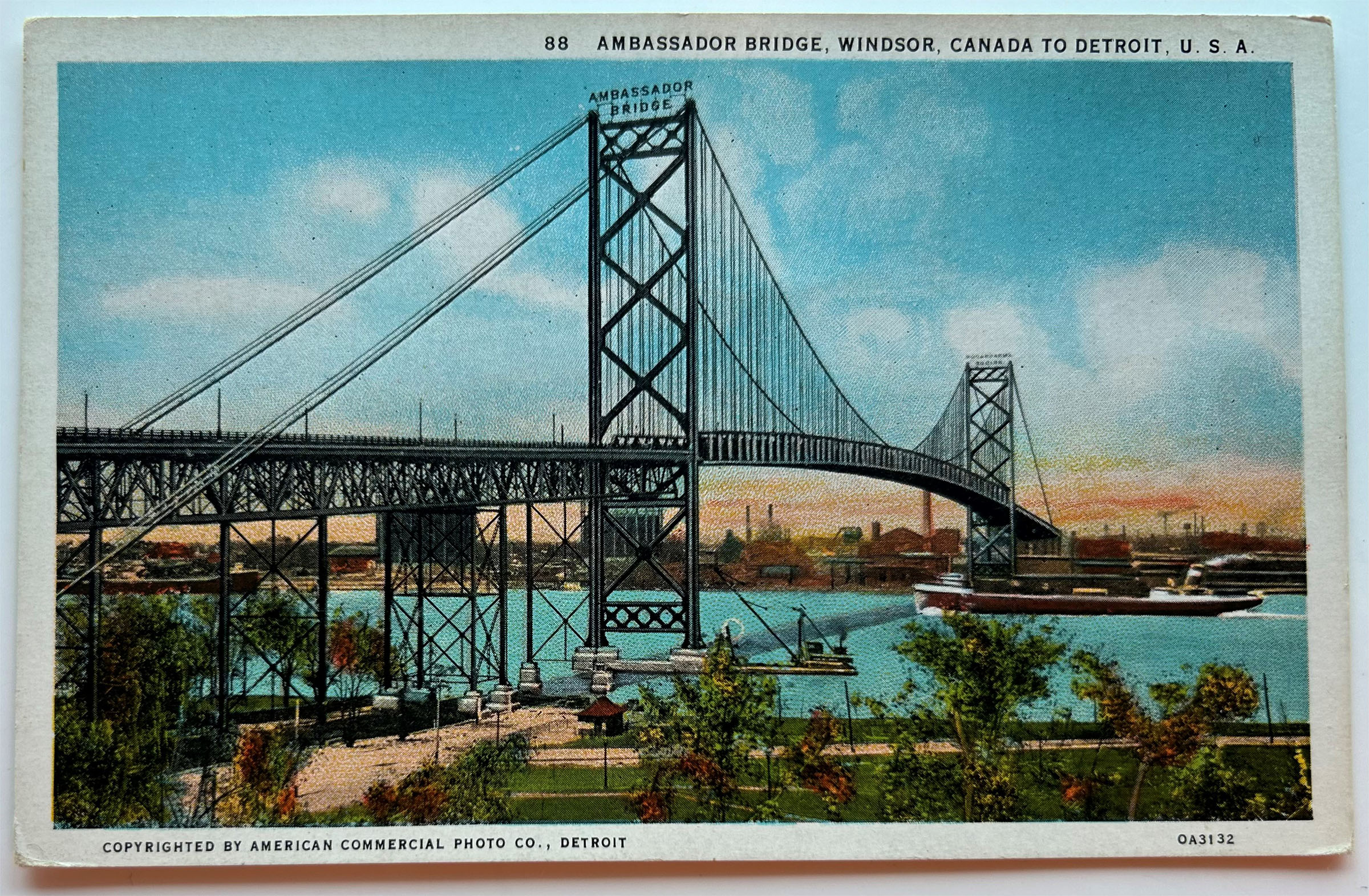

But it was also a window into the African American experience I could never fully know, and that intrigued me. I had started to see the white flight, abandonment, and segregation that split greater Chicagoland asunder as the great defining original sin that corrupted the area. Highways came to divide white and minority neighborhoods in both Chicago and the Calumet Region. I went to high school about a block south of Gary when it was still the murder capital of the United States, where as many as 13,000 vacant buildings have rotted in shameful testament to people’s unwillingness to live next door to people who look differently. The sins of our forefathers scarred the landscape with blight, boarded-up storefronts, and rubble-strewn buildings with collapsed roofs. Native Son explores racial discrimination that sadly remains just as relevant as ever. A recent HBO adaptation, instead of putting Bigger through a show trial, modernized his plight by having Bigger gunned down extrajudicially by trigger-happy police.

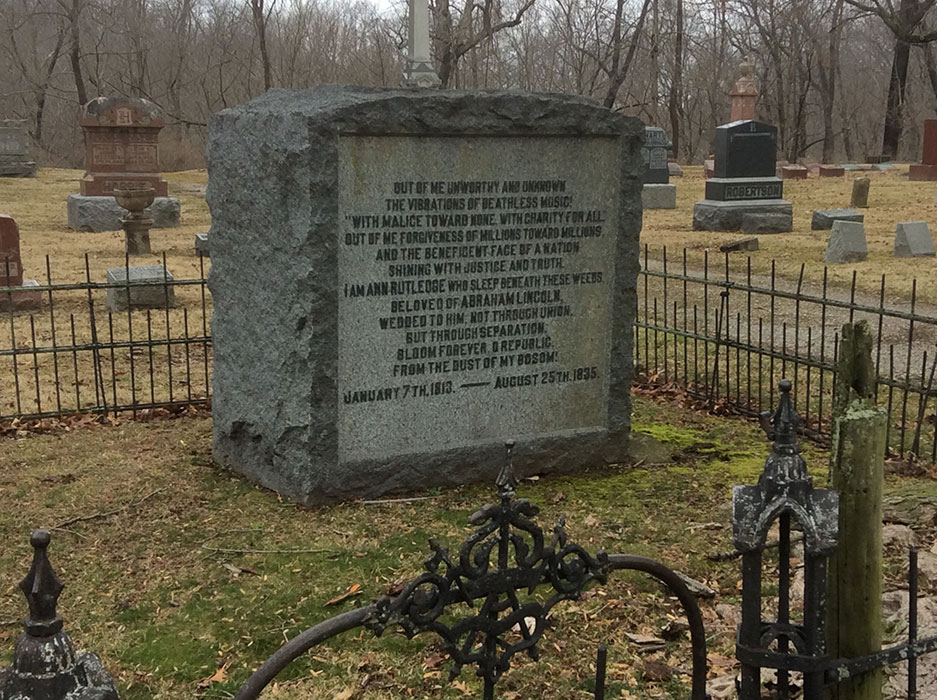

Wright grew up in Jim Crow Mississippi and moved as a young adult to Chicago’s South Side, his family following the Great Migration from the South to the more prosperous industrialized cities of the North. He spent the most time in one place on the second story of a row house in Bronzeville, a largely residential neighborhood flanking Grand Boulevard (now called Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive). He lived with family in a two-story building with a cream-colored brick façade, bay windows, a tiny patch of lawn, and an entrance with stone stairs and relatively unembellished Greek pillars, the most modest home in a strip of taller and more architecturally extravagant houses. Today, the home is privately owned, and no tours are offered, but you can admire the solid masonry of the stone-and-brick exterior and enduring handiwork of craftsmen from 1893, when it was built.

Wright lived on that densely populated stretch of S. Vincennes Ave. in his early 20s, working as a postal clerk until the Great Depression cost him that position. He went on to bounce around the city, working a series of unskilled jobs, but spent that formative period in the Black Metropolis that produced many intellectuals, artists, and musicians, such as Gwendolyn Brooks, Louis Armstrong, Ida B. Wells and Sam Cooke.

During his downtime, Wright studied great authors and started to pursue his literary ambitions. He contributed to the area’s vibrant culture, founding the South Side Writers Group and the literary journal Left Front as he started to publish his own poetry. He also began his first novel, Lawd Today!, which he finished in 1935 but wasn’t published until after his death decades later.

There’s not much to see now on the quiet residential street other than a plaque designating the house as a Chicago Landmark, but the modestness of the abode that helped nurture Wright to greatness is the point. Ninety years after he lived and started writing there, the neighborhood continues to hum with culture. There’s the Harold Washington Cultural Center, the Southside Community Art Center, Room 43, the Bronzeville Art District Trolley Tour, and the Bronzeville Walk of Fame, among many other points of interest.

Though just south of the glittering skyscrapers of the Loop, the majority-black Bronzeville often gets as overlooked as it was when Wright lived there from 1929 to 1932. In Native Son, Mary Dalton tells Bigger, “I’ve been to England, France and Mexico, but I don’t know how people live ten blocks from me. We know so little about each other.” Even today, many suburbanites and recent Big Ten grads transplanted to the North Side have never set foot in the rather genteel neighborhood. I frequently attend White Sox games just across the highway, but it feels a world away. The divisions that doom young men like Bigger Thomas still stand today in great sweeping corridors of concrete and ingrained prejudice.

The descendent of steelworkers, author and award-winning journalist Joseph S. Pete hails from the Calumet Region just outside Chicago, where the oil refinery flare stacks burn round the clock and the mills make clouds. His literary work and photography have appeared in more than 100 journals, including Proximity Magazine, Tipton Poetry Journal, O-Dark-Thirty, Line of Advance, As You Were, Chicago Literati, Dogzplot, Proximity Magazine, Stoneboat, The High Window, Synesthesia Literary Journal, Steep Street Journal, Beautiful Losers, The First Line, New Pop Lit, The Grief Diaries, Gravel, Junto, The Offbeat, Oddball Magazine, The Perch Magazine, Bull Men’s Fiction, Rising Phoenix Review, Thoughtful Dog, shufPoetry, The Roaring Muse, Prairie Winds, Blue Collar Review, The Rat’s Ass Review, Euphemism, Jenny Magazine, and Vending Machine Press.