Sarah Smarsh

Rural Kingman County

Murdock, Kansas

By Taylor Krueger

During Sarah Smarsh’s childhood, driven by poverty and necessity, she moved frequently between the Kansas prairie and nearby metropolitan Wichita. Born on the precipice of the 1980s Farm Crisis, Smarsh received an inheritance of generational poverty and a nomadic lifestyle. During her youth, she would move between Kingman and Sedgwick counties 21 times before she turned 18. Her experience of the Kansas landscape and the people who call it home deeply influence her work as a writer and journalist, highlighting economic inequality and culture in rural America and bridging the cultural divide between urban and rural spaces.

“The countryside is no more our nation’s heart than are its cities, and rural people aren’t more noble and dignified for their dirty work in fields. But to devalue, in our social investments, the people who tend crops and livestock, or to refer to their place as ‘flyover country,’ is to forget not just a country’s foundation but its connection to the earth, to cycles of life scarcely witnessed and ill understood in concrete landscapes.”

Like Smarsh, my roots run deep through the soil of the Kansas prairie. One side of my family has grown and harvested wheat in northwest Kansas for five generations. On the other, my grandfather was raised on a farm and began his career driving a Wonder Bread truck through southeast Kansas, delivering the final product to consumer’s grocery shelves. Intergenerational values of self-reliance, moderation, and grit are narratives that shaped my upbringing.

My first encounter with Smarsh’s writing was Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth (2018), which highlights the tension between rural values and the systemic issues that undermine them.

“I was raised to put all responsibility on the individual, on the bootstraps with which she ought pull herself up. But it’s the way of things that environment changes outcomes. Or, to put it in my first language: The crop depends on the weather, dudnit? A good seed’ll do ’er job ’n’ sprout, but come hail ’n’ yer plumb outta luck regardless.”

As a licensed marriage and family therapist, I’ve learned the context that shapes us is not evenhanded, contrary to the myth of meritocracy. The principles of self-reliance that have helped rural people endure harsh conditions for centuries are the same values that create barriers to mental health care. In a place where your value as a human being is dependent on being useful, shame becomes common. Many of my psychotherapy clients believe they are the source of the problem. My training in systems theory, however, leads me to highlight reciprocal relationships, emphasizing instead that individual problems are systemic, created by larger forces in the family, community, and society.

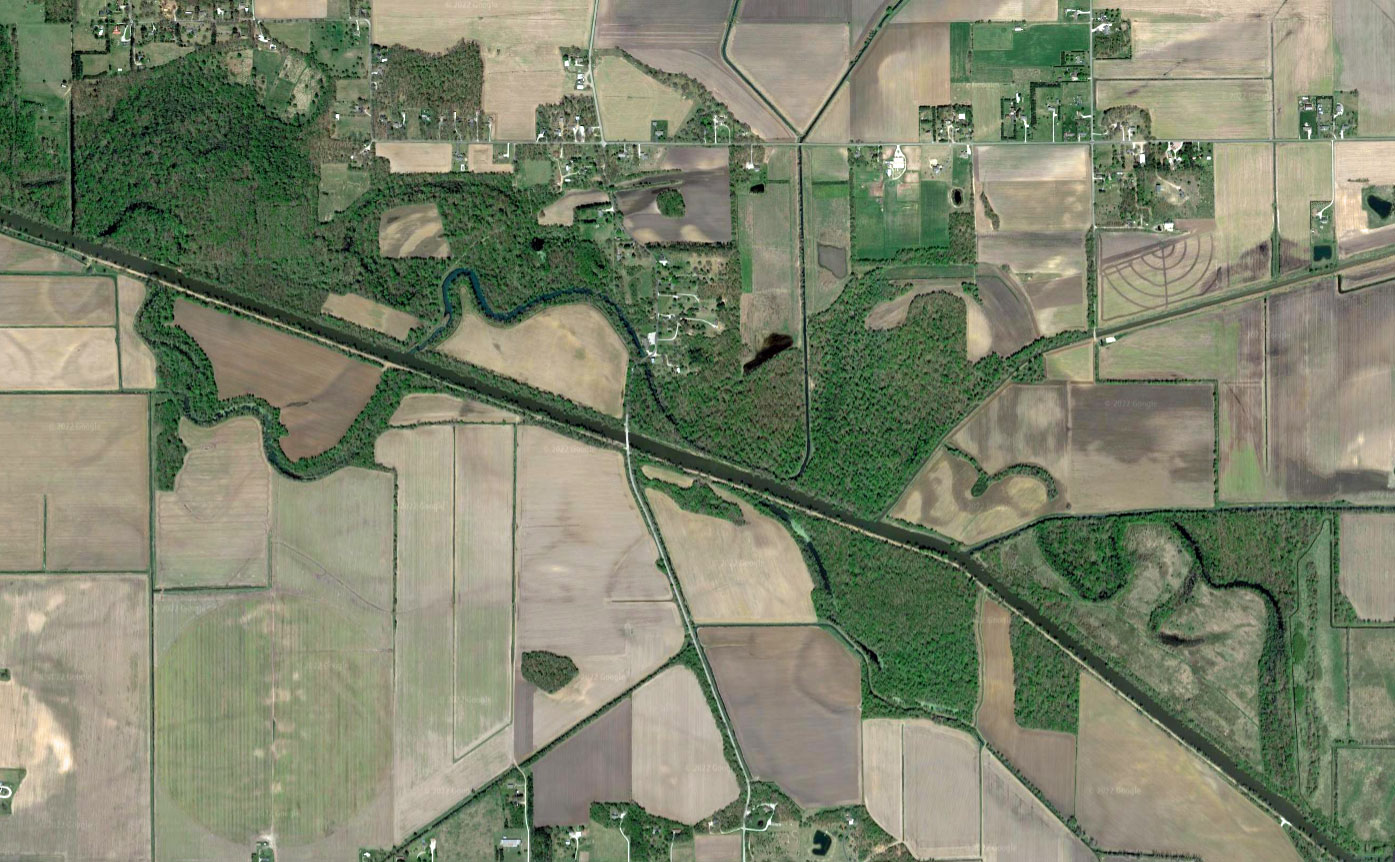

Smarsh describes her early years observing the doctrine of self-reliance in a trailer next door to a farmhouse owned by her Grandma Betty and her husband, Arnie. The farm was located west of Wichita in the lowlands of south-central Kansas, straddling the High Plains and the Red Hills, with distinct red-brown soil stretching across the horizon. To the north is Cheney Reservoir, a man-made lake used to provide a water supply to the people of Wichita, with boats bobbing on the surface and campgrounds lining the shore. The reservoir borrows water from the nearby Ninnescah River, which means “sweet water” to the Osage Nation, who would be driven off their land nearly a century before the reservoir was constructed.

On a winter afternoon, I drive slowly around unmarked roads near Cheney Reservoir towards Kingman County, witnessing the expanse of prairie earth, water, and sky. I park my car north of the unincorporated community of Murdock, population approximately 37, near a boundary of barbed wire. The sound of stillness familiarly greets my ears as I reorient myself to the “isolation of rural life,” that Smarsh describes in Heartland. In early February, the fields are hushed and hibernating. On an unseasonably warm day, the colors glare under the winter sun. The enormous sky is a bright, clear blue with sweeps of watercolor wispy white clouds low on the horizon. Red dirt sticks to the tires of my car. Green rows line wheat fields stretching forward to tree lines ahead, limbs barren until spring comes around again. I watch the roots resting quietly, pausing as the cold air sits still in anticipation. My father taught me that wheat knows intuitively in its cells the exact right moment to spring forth from the earth, green stalks transforming into waving gold strands for harvest. Undeterred by hailstorms, fire, and drought, the crop continues to grow and change. In this Kingman County wheat, I see the great mystery of knowing your roots are deeply planted, and still not knowing what will become.

There is a mystical relationship that ties Kansans to this land. Smarsh reminds us in Heartland that even in leaving, “no matter where you ended up, like every immigrant you’d still feel the invisible dirt of your motherland on the soles of your feet.” In the same way Kansans are connected to the land, she writes, we are also connected to each other:

“Of all the gifts and challenges of rural life, one of its most wonderful paradoxes is that closeness born of our biggest spaces: a deep intimacy forced not by the proximity of rows of apartments but by having only one neighbor within three miles to help when you’re sick, when your tractor’s down and you need a ride, when the snow starts drifting so you check on the old woman with the mean dog, regardless of whether you like her.”

Standing on the side of the road in Kingman County, with only the wind for company, I feel small in my skin. In this sea of grass and red dirt, I am engulfed by the beautiful, terrible, and uncontrollable earth. Yet, in my aloneness, I am comforted by the sight of farmhouses rising quietly ahead. Looking out at this wild, expansive ecosystem of the prairie, the generosity and gregariousness of small, isolated communities provide me with a sense of hope in the face of systemic ambiguity. Despite the great spaces between rural people, a unique camaraderie binds us together. I’m reminded of a principle in systems theory indicating how change in any one part of the system evokes change on a larger scale. Through her wisdom and writing, Sarah Smarsh calls for collective change in our communities by providing clear testimony about the people of rural America, the landscape, and the reality of systemic issues that affect us every day.

Taylor Krueger is a licensed marriage and family therapist providing psychotherapy to women and children in her rural community. She studied literature and psychology at Kansas State University, and received her Master of Science in family therapy from Friends University. She was raised in Rooks County, Kansas, and her writing is influenced by the places she has called home. She lives in Newton, Kansas, with her husband and two young sons.

![Twain in study window 1903 Mark Twain in Study Window [1903]](https://newterritorymag.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Twain-in-study-window-1903.jpg)