Aldo Leopold

The Leopold Shack

Baraboo, Wisconsin

By Marc Seals

I am not a Midwestern native — I was raised in the woods and swamps of north Florida, far from the Driftless Region of Wisconsin (where I now live). As a result, I was not familiar with Aldo Leopold or his work when I moved to Baraboo sixteen years ago. Soon after arriving, I picked up a copy of Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There, and I had not finished many pages before realizing that literature lost a fine nature poet when Leopold decided to dedicate his career to forestry. For example, Leopold writes, “One swallow does not make a summer, but one skein of geese, cleaving the murk of a March thaw, is the spring.” Or “There are two spiritual dangers in not owning a farm. One is the danger of supposing that breakfast comes from the grocery, and the other that heat comes from the furnace.” And don’t get me started about the chapter where Leopold remembers watching the green fire fade from the eyes of a dying old wolf.

Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac, published the year after he died in 1948, has been recognized as a foundational text in the field of environmental ethics for over fifty years. It has been ten years since I finally made the pilgrimage to the Leopold shack, riding my 1973 Peugeot road bike to Leopold’s farm just outside of Baraboo. I dismounted and peered in the windows, where I could see bunkbeds, a stone fireplace, the rustic kitchen — calling it “simple” would be an extreme understatement. Regardless, I knew that I was standing on sacred ground. This might seem an odd pronouncement, given the fact that the shack is a converted chicken coop (since no other building on the property was worth salvaging), but hear me out….

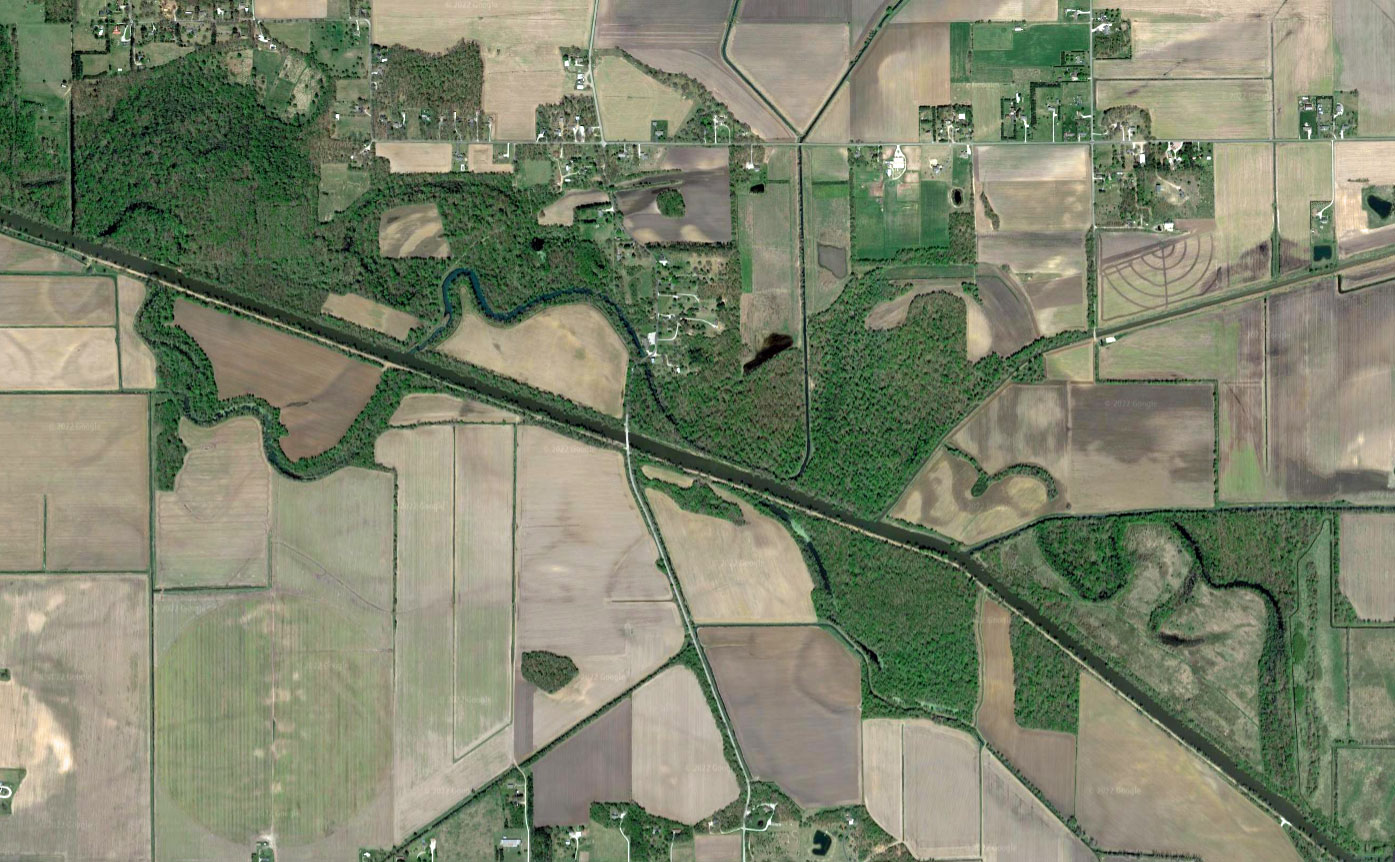

Leopold purchased the ruined farm on the shore of the Wisconsin River in 1935 for a mere eight dollars an acre to use the land as a sort of laboratory — he wanted to restore the natural forest and prairies. The experience helped him finalize what he terms the “land ethic.” Leopold calls for a new relationship between humanity and nature, writing, “In short, a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members.” He demonstrated this respect in his efforts to restore the property to its natural state. Leopold and his family planted over 40,000 trees on their frequent retreats from Madison, and the land is unrecognizable today. This “sand county” farm was not much good for farming, but it makes a great forest and prairie.

A Sand County Almanac is a memoir, a journal, a philosophical treatise, and more. Leopold honed his environmental philosophy on this property, and that’s why it’s sacred. There are not many chicken coops that helped give rise to a system of ethics. Beyond that, I struggle to convey what the shack means. I built a birdhouse replica of the shack last winter, and it turned out so nicely that the Aldo Leopold Foundation has supplied me with wood from trees planted by Aldo Leopold so that I can make birdhouses as a fundraiser for the Foundation. I’ve taken literature classes to the shack just after we finished reading A Sand County Almanac, where I was able to witness the wonder on the faces of students who drank water from original pump. I have driven out to the shack with Noah, my biology professor friend, on a ten-degree January day; we stood on the shore of the Wisconsin River and read our favorite passages to each other (for as long as we could take the cold). And I rarely cycle past without stopping in for a visit.

The Aldo Leopold Foundation, located in a wonderful visitor’s center just down the road, is continuing Leopold’s work, restoring the surrounding prairies to their original state. In short, every visit to the shack — and every rereading of A Sand County Almanac — feeds my soul.

Marc Seals is a professor of English at the Baraboo campus of the University of Wisconsin-Platteville, where he teaches courses in American literature, composition, and film. He has published articles and book chapters on authors such as Ernest Hemingway, Raymond Chandler, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gwendolyn Brooks, Dashiell Hammett, and Zona Gale. A native of the Deep South, he has grown to love the Midwest.

![Twain in study window 1903 Mark Twain in Study Window [1903]](https://newterritorymag.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Twain-in-study-window-1903.jpg)