Edgar Lee Masters

Ann Rutledge’s Grave

Petersburg, Illinois

By Jason Stacy

As a boy, I found it unsettling that Edgar Lee Masters anthologized the dead in an Illinois cemetery that never existed. Spoon River Anthology’s ghosts haunted the same rich Illinois soil I walked upon, stared out at fields like the ones that rolled by the window of my school bus, and spoke in accents that echoed mine, but these people were nowhere to be found. Doubly spectral, they were the dead neighbors that never were. Reading a frayed copy of Masters’s book brought home by my mother, an English teacher, I felt as if I were peering into a legendary Illinois that dissipated the closer I got to it.

But now that I’m older, I am at peace with the legends. The trick is not to get too close.

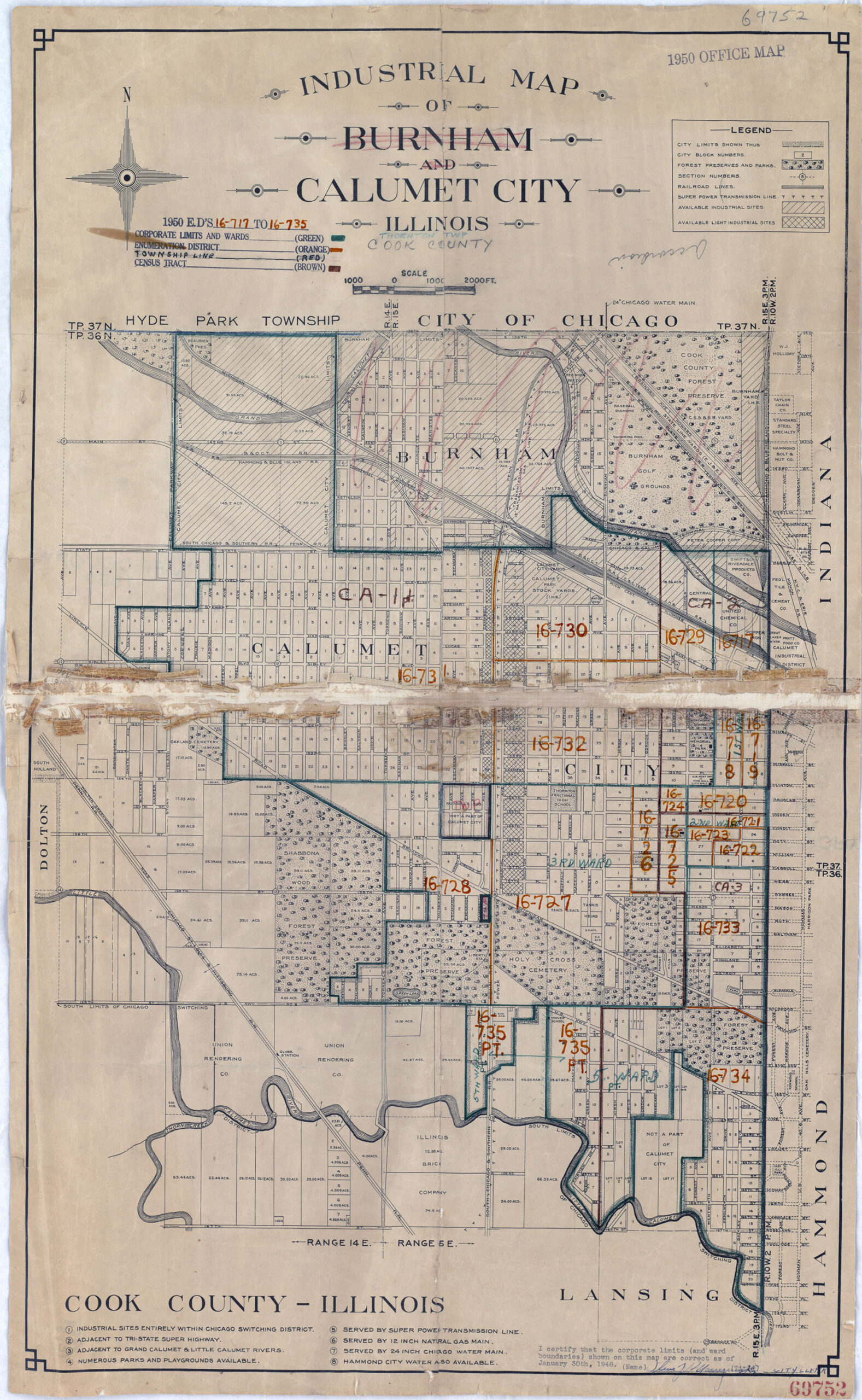

Masters himself is buried in a very real place: Oakland Cemetery in Petersburg, Illinois, just about at the center of the state, a short drive from Springfield and down the road from New Salem, the pioneer community where Abraham Lincoln lived for a time. Petersburg is in the Illinois part of Illinois.

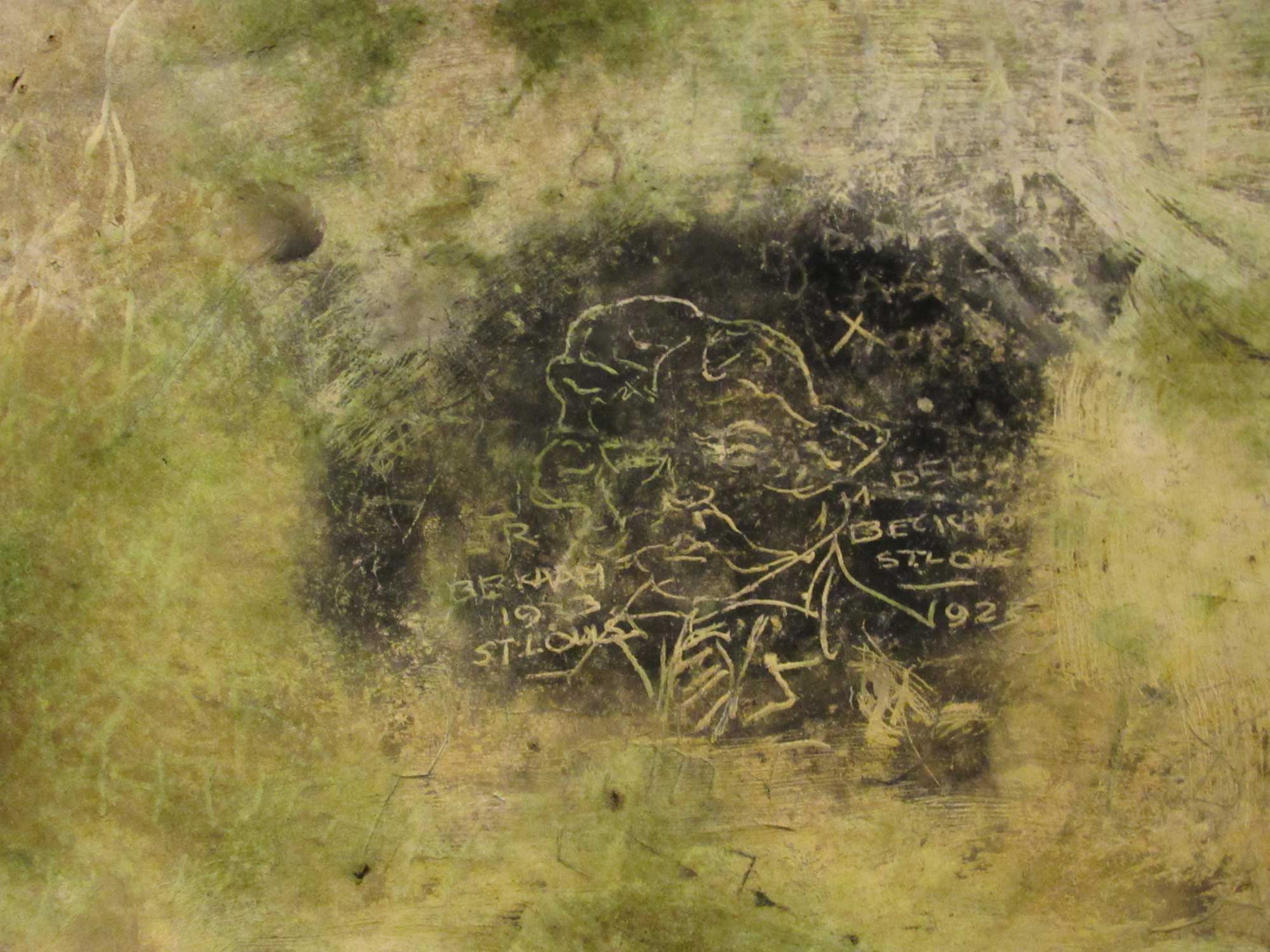

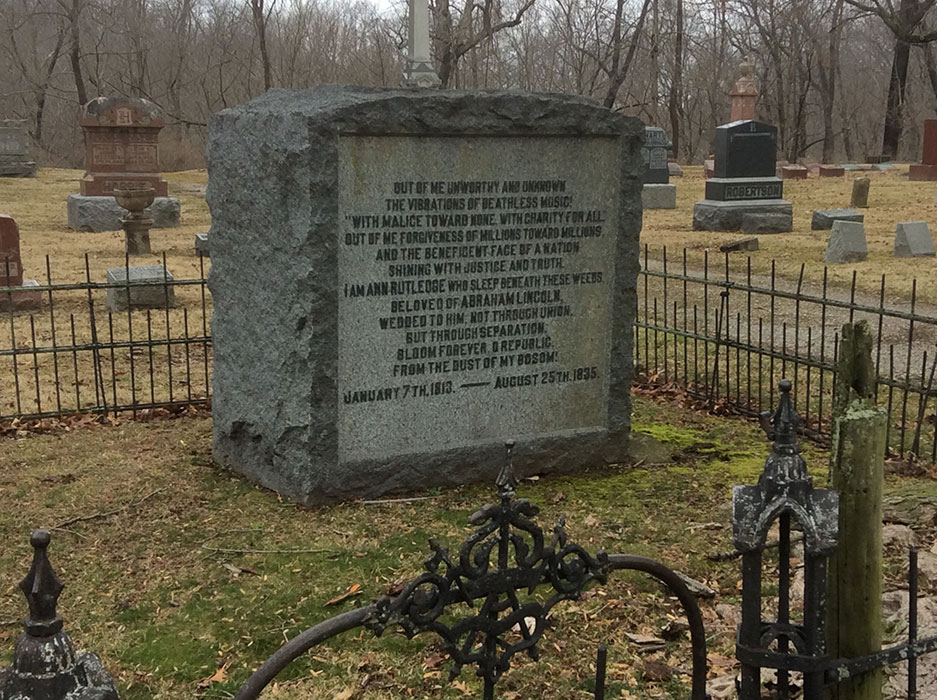

Masters rests only a few feet from a legend he helped make: Ann Rutledge, thought to be the one love of Abraham Lincoln’s life. About twenty yards away, down one of the main paths of the cemetery, a low iron fence surrounds a solid block of granite, on which is engraved a poem by Masters:

Out of me unworthy and unknown

The vibrations of deathless music;

“With malice toward none, with charity for all.”

Out of me the forgiveness of millions toward millions,

And the beneficent face of a nation

Shining with justice and truth.

I am Ann Rutledge who sleep beneath these weeds,

Beloved in life of Abraham Lincoln,

Wedded to him, not through union,

But through separation.

Bloom forever, O Republic,

From the dust of my bosom!

Rutledge died of typhoid fever in 1835 and was originally buried in the Old Concord graveyard about five miles from Petersburg. After Lincoln’s death, his former law partner, William Herndon, claimed in his biography of the president that Rutledge was the one true love of Lincoln’s life. Her death at twenty-two threw the future president into an emotional crisis and, according to Herndon, Lincoln never loved any woman as much again. As the living Lincoln faded from popular memory after the Civil War, Rutledge’s ghost began to haunt the legends of the fallen president. These legends turned central Illinois into a destination for secular pilgrims, and she became the key to understanding Lincoln’s combination of melancholy and stoic fortitude.

To capitalize on the legend, local undertaker and furniture dealer Samuel Montgomery exhumed Rutledge in 1890 from the Old Concord graveyard and reburied what was left of her — two bones, a little hair, some bits of cloth — in Oakland Cemetery, where he was part owner. Montgomery hoped this location would prove convenient for visitors and fortuitous for the town. Twenty-five years later, in 1915, Rutledge was reburied again, this time symbolically, when Edgar Lee Masters planted her in Spoon River’s fictional cemetery. In 1921, at the height of Masters’s popularity, her epitaph from Spoon River Anthology was engraved on a new monument in Oakland Cemetery. These days, tourists commune with the legend of Rutledge that William Herndon perpetuated, by the grave that Samuel Montgomery filled with a few remains, under a fictional epitaph written by Edgar Lee Masters.

Outside of town, in the Old Concord graveyard, a small headstone marks Ann’s first resting place. It appeals to visitors’ desire for authenticity by telling them that this lonely spot in an out-of-the-way field is, in fact, “where Lincoln wept.” But when I drive through Petersburg, I visit Ann at Oakland Cemetery. The legend is better there.

Jason Stacy grew up in Monee, Illinois. Since 2006, he has served as a professor of history and social science pedagogy at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. His latest book project, Spoon River America: Edgar Lee Masters and the Myth of the American Small Town, is under contract with University of Illinois Press.

![Twain in study window 1903 Mark Twain in Study Window [1903]](https://newterritorymag.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Twain-in-study-window-1903.jpg)