Hugo Martinez-Serros

South Chicago City Dump

Chicago, IL

By Emiliano Aguilar

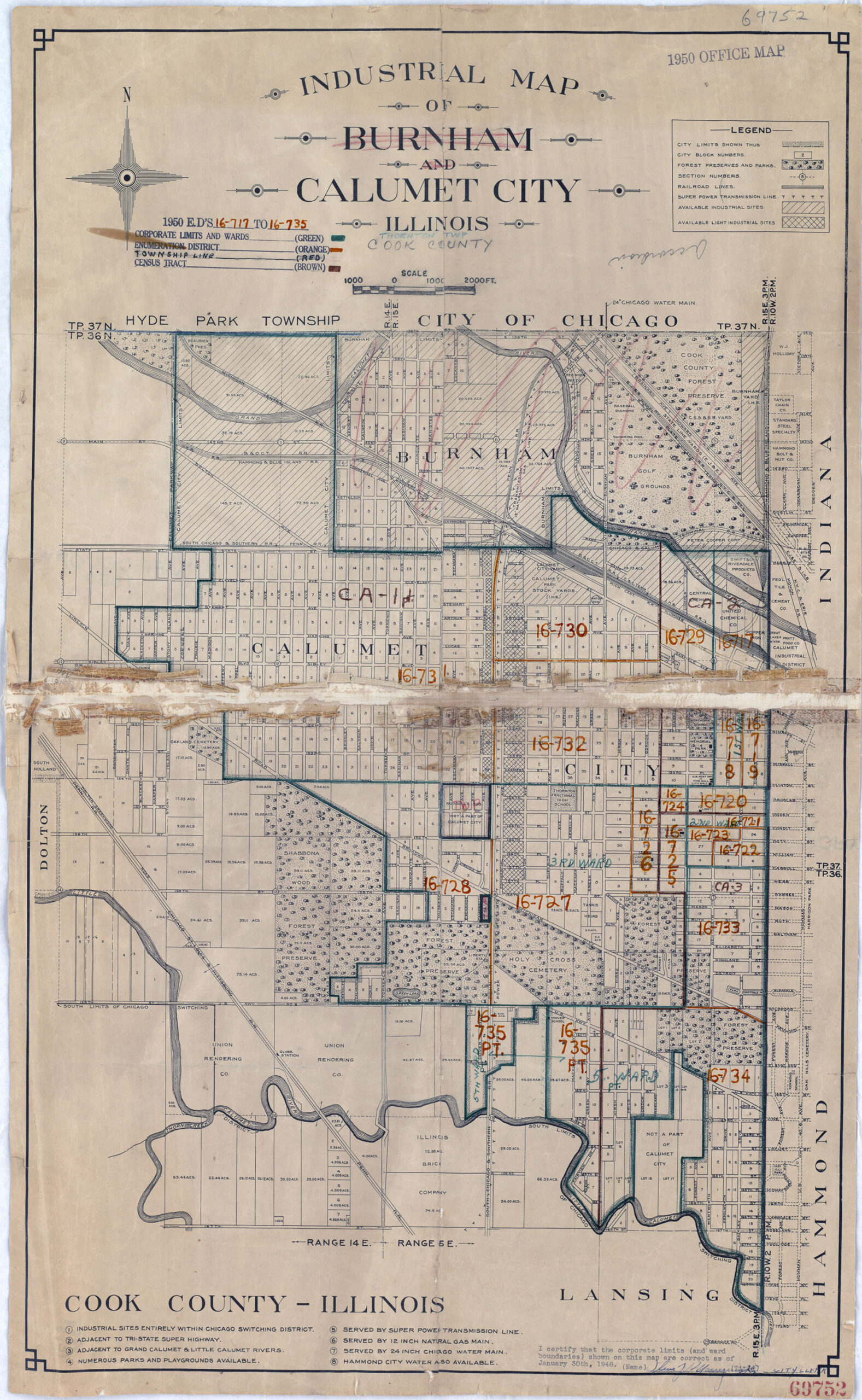

Chicago’s South Side is littered with the remains of its industrial past. From the façade of the former US Steel South Works to sites bustling with activity, such as the Pullman National Monument. I grew up in the shadow of Chicago, over the state line in the appropriately named East Chicago, Indiana. My hometown and much of Northwest Indiana, often referred to as “Da Region,” looked more like Chicago and shared more of its history than other parts of Indiana. We even have our own ruins, such as the abandoned warehouse of the Edward Valve Company, the half-scraped ruins of Cleveland Cliffs (formerly ArcelorMittal and before that Inland Steel), and the ever-shrinking Marktown.

This world comes alive in the short stories of Hugo Martinez-Serros, whose family arrived to work in the region’s steel industry. Like them, tens of thousands of people arrived on the South Side to labor arduously in often unsafe environments. Ethnic Mexicans arrived as solos, single men, ahead of their families. These pioneers paved the way for their families and extended networks.

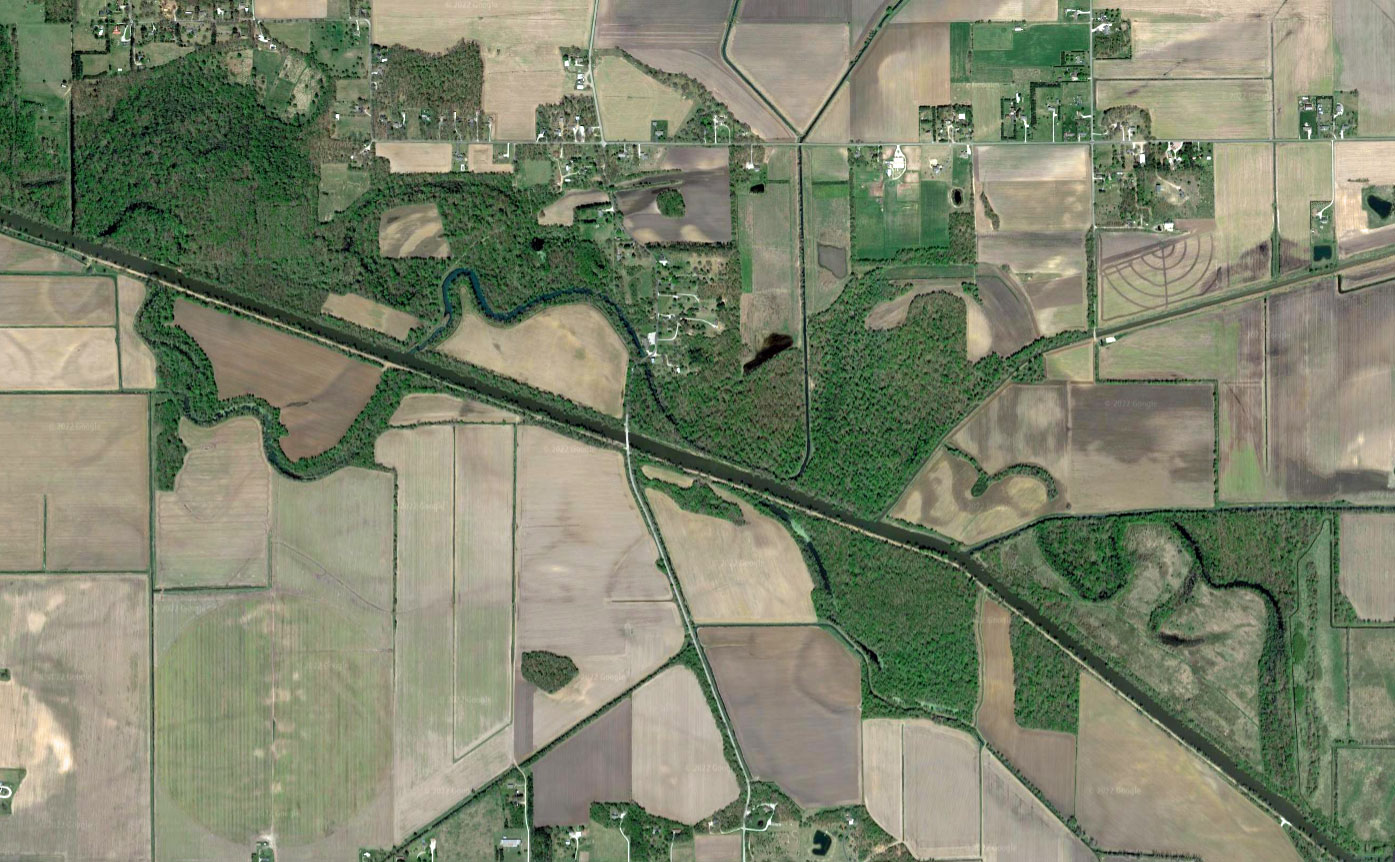

In “Distillation,” first published in The Last Laugh and Other Stories (1988), Martinez-Serros recalls a family drive from their home on the South Side to a municipal dump across the neighborhood. Recalling the weekly Saturday drive southward from their home through alleys crossing 86th, 89th, and 95th Streets, Martinez-Serros describes their final destination vividly: “Before us was the city dump — a great raw sore on the landscape; a leprous tract oozing flames, smoldering; hellish grounds columned in smoke, grown tumid across years.” The narrator, along with his family, sifts through the trash, looking for items to salvage. Together they search for items to sell and discarded produce as a means to survive during the Depression.

As clichéd as it might be, what is one person’s trash if not another person’s treasure? I first read Hugo Martinez-Serros after picking it up from the free box at the Purdue University Northwest library. While the book had seen better days, it showed clear signs of love: dog-ears, a weathered spine, yellowed pages, scribblings from an earlier reader, and a fair amount of shelf-wear. Salvaging this copy from among discarded textbooks and novels, I discovered Depression-era South Chicago. While familiar to me in my work as a historian, thanks to scholars like Gabriela F. Arredondo and Michael Innis-Jiménez, the world Martinez-Serros described differed greatly from the region I knew as a lifelong resident.

Northwest Indiana and Chicago’s South Side are part of the Rust Belt. Once an industrial sprawl of hundreds of thousands of jobs manufactured hundreds of items, the region began to decline in the 1970s and 1980s. However, the Rust Belt is not simply a ruin, some vestigial piece of our shared past. For decades, cities have worked to revitalize their communities and, in some cases, evoke their industrial heritage. In the 1990s, Northwest Indiana communities turned to the gaming industry and lakefront casinos to supplant the loss of manufacturing jobs.

These revitalization plans did not exclude piles of trash. In the 1990s, the City of Chicago built Harborside International Golf Center on top of the old dump. Childhood searches for scrap to sell or barely expired food were replaced by golfers scouring the rough for balls that went astray. In high school, I played on one such dump-turned-golf course as a part of my varsity team. Like Martinez-Serros and his family sifted through the refuse and remains at the municipal dump, I played on the former dump. These carefully designed courses of bright green fairways are nestled among industrial complexes. On clear days, you can see the iconic Chicago skyline.

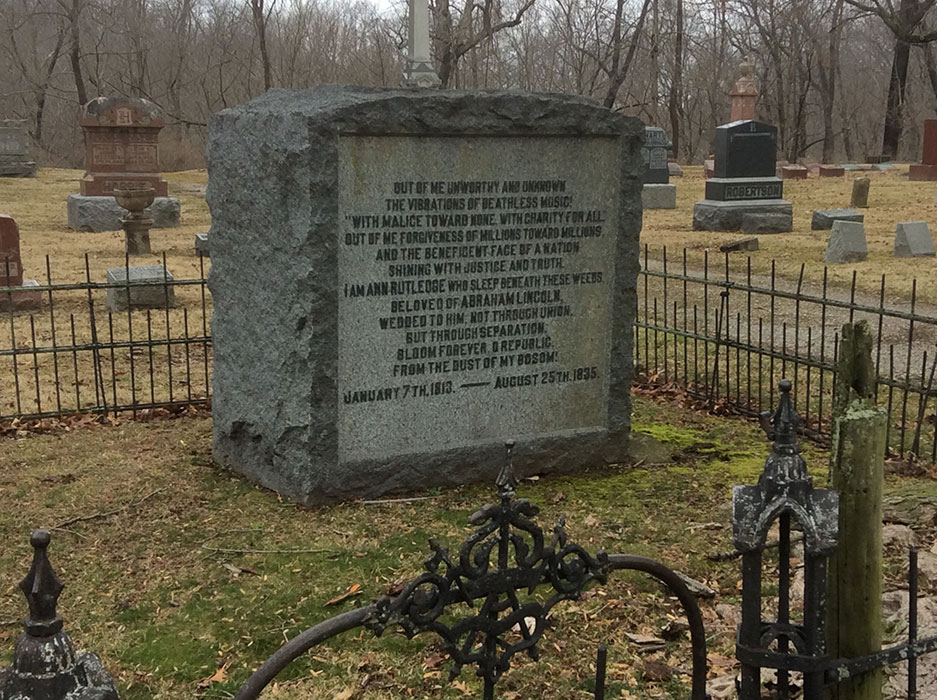

The region’s residents turned heaping piles of trash into a site of recreation and frustration. While the narrator retold joyful and almost play-like salvaging, this was coupled with the frustration and fear of his brother falling into a pile of trash. This joy and fear of garbage-diving became replaced with the joy of a long drive and the frustration of a mixed putt. However, the presence of the golf course for recreation is a mixed bag. While many praise the efforts of turning trash into treasure, changes to the Chicagoland landscape are not limited to trash heaps. In some cases, rich historical sites, such as those on the Most Endangered List, are under threat of removal in the name of progress. While some residents are content with this change, others view it as a loss of the shared heritage and history of the area. Although many deride the area, which still suffers from the harmful legacy of environmental injustice, those of us who remain continue to chip off the rust and show that Da Region is a vibrant home.

Emiliano Aguilar Jr. is a native of East Chicago, Indiana. Currently, he is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend. His manuscript in progress, Building a Latino Machine: Caught Between Corrupt Political Machines and Good Government Reform, explores the complexities of the ethnic Mexican and Puerto Rican community’s navigation of machine politics in the 20th and 21st centuries to further their inclusion in municipal and union politics in East Chicago, Indiana. His writing has appeared in Belt Magazine, Immigration and Ethnic History Society’s Blog, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of America History, The Metropole, the Indiana Historical Society Blog, and Building Sustainable Worlds: Latinx Placemaking in the Midwest (University of Illinois Press, 2022).

Photo by Cameron Smith, culinary director at Infuse Hospitality in Chicago. He can be found on Instagram at @iamfood0079.

For the most recent version of the Calumet Heritage Area Most Endangered List, please visit the Calumet Heritage Partnership.

![Twain in study window 1903 Mark Twain in Study Window [1903]](https://newterritorymag.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Twain-in-study-window-1903.jpg)