James Tate

Cow Creek Crossing

Pittsburg, Kansas

By Leslie VonHolten

Each James Tate poem presents itself like a welcoming trailhead — happy, sunshiney even. It is not until you are deep in the woods of it all before you sense the lurking weirdness. For example, in “The Government Lake,” a trip to the toy store ends with a discomfiting acceptance of violence. Or the reader of “Awkward Silence,” on her porch, annoyed by helicopters mating overhead. Or how about those late-in-life lovers, mugged by musicians in “The Hostile Philharmonic Orchestra”?

If you think these are strange set-ups, how about this: Tate, a surrealist, absurdist Midwestern poet won the Pulitzer Prize (1992) and the National Book Award (1994) for his odd dreamscapes. What a world.

Tate lived many places that rightfully claim him, but it was as a student in Pittsburg, Kansas, where he learned that he was a poet. This landscape of disturbed prairie, coyote howls, and broad days opened the deep attention he needed to see the absurd in everyday life.

I’m all for the magic carpet ride Tate gives us, but it is “Manna” from his first collection that grounds me. A little sentimental, yes, but its alignment of solitude and connection under the night sky hits me square in the sternum. It is my all-time favorite poem set in Kansas.

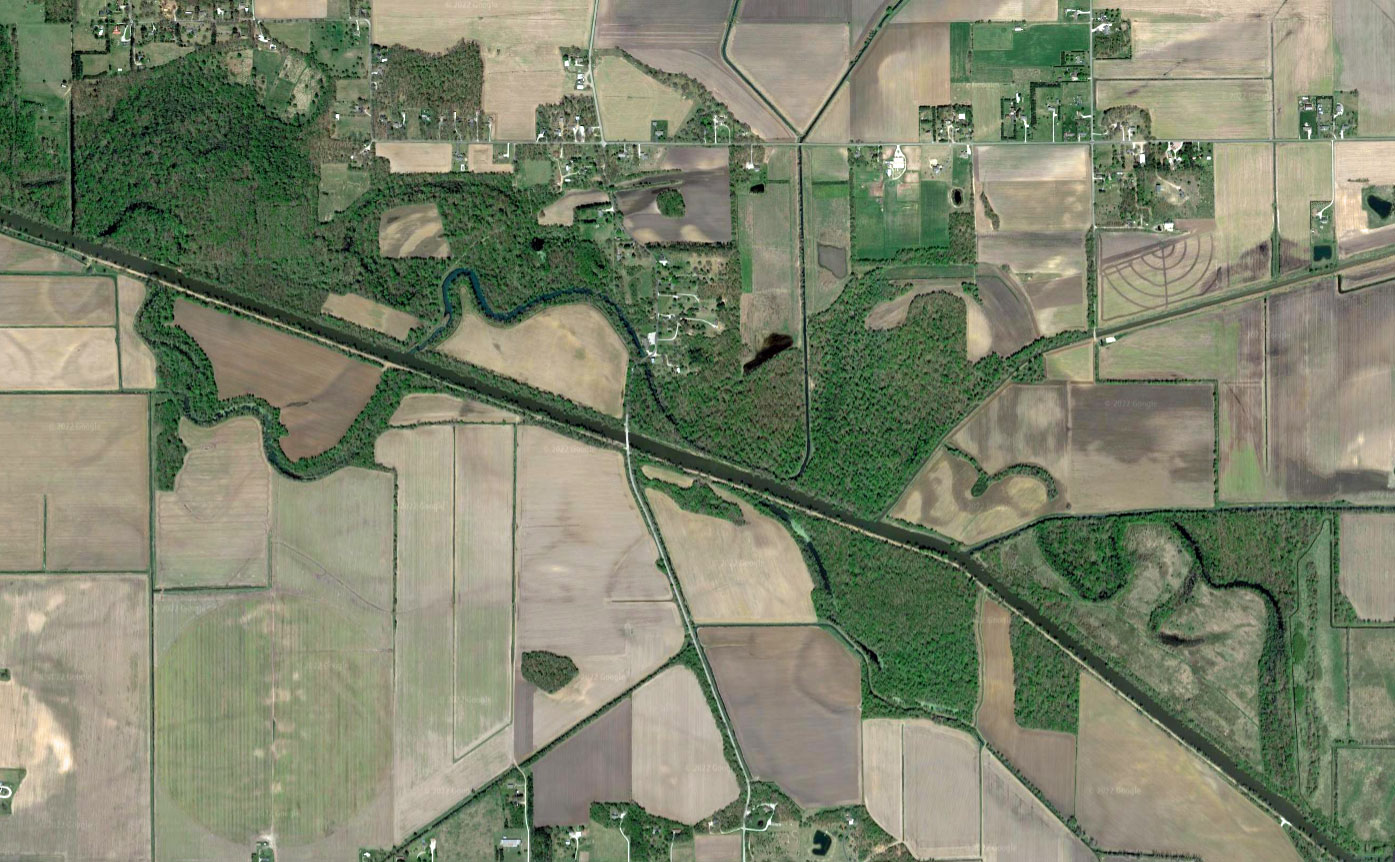

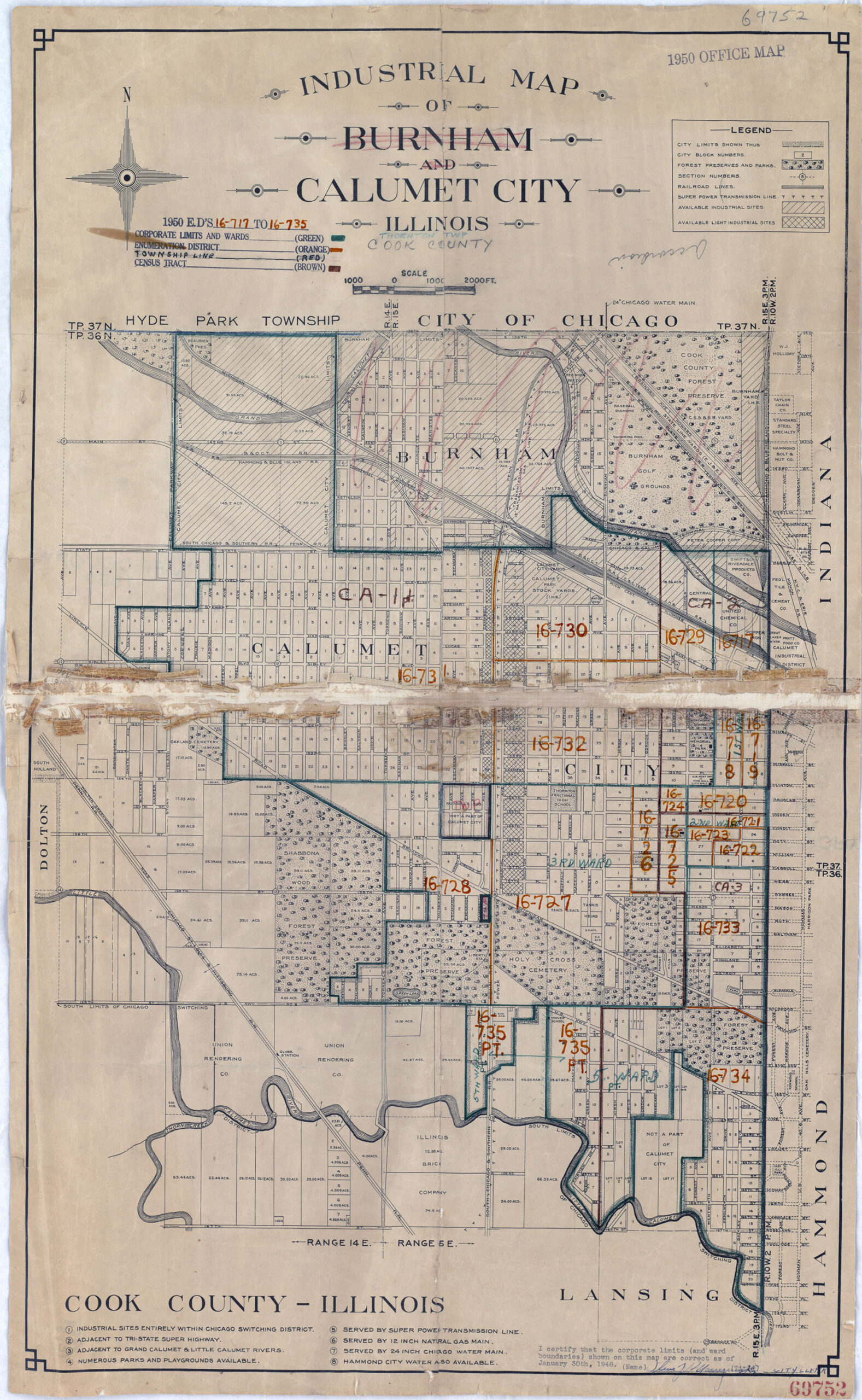

Train tracks in Pittsburg have changed since Tate wrote those lines in 1967. Many spurs have been pulled out or paved over, and the depot is now an event center. But you can still find slow, flat and open crossings on the quieter edges of town. Tate’s miraculous provision of the poem likely happened as he walked home along West Hudson Street. Poets and other bohemians were known to drink on the trestle bridge spanning nearby Cow Creek, the setting of another poem in the collection.

Rural Kansas is rarely seen as a gateway to surrealist thought, but look closer and consider. Pittsburg is surrounded by the land-scars of mining, small pits and hills that undulate throughout the county. In the early 20th century, immigrants from all over the world came to southeast Kansas to work in the “gopher hole,” strip, and shaft mines. Many were from Eastern Europe, and the area became known as the Little Balkans. It’s a heritage that echoes still: until the pandemic, you could polka dance at Barto’s Idle Hour in neighboring Frontenac on Saturday nights. Artist-painted fiberglass replicas of coal buckets honor the town’s mining past.

This is also a land of gorillas. They are everywhere. The Pittsburg State University mascot is the proud town identifier — even the trash bins in front of each house are gold and red, and cement silverbacks decorate yards in every neighborhood.

The historical juxtaposition exposes the absurdity: Pitt State students selected the gorilla in 1925, while just three years earlier, the town made international news when 6,000 women and children marched for three days to protest poor labor conditions in the mines. The Kansas National Guard was deployed to establish order; a New York Times reporter dubbed the women the “Amazon Army.” They were lauded as heroes in the mine camps.

It’s a surreal mix, these legacies of college rah-rah comingling with a socialist labor movement. “I sure miss that country; I am really beginning to feel or see the roots I have there,” Tate wrote to his instructor Eugene DeGrusen in 1966. “It takes time and distance I guess to see that kind of thing, but I see it now and I’m proud of it. Not that I write bucolic verse or even use much naturalistic imagery, but I am primitive in a contemporary way, if such a phrase can be allowed.”

… but I am primitive in a contemporary way … Fiberglass coal buckets, Saturday night polka music, and gorillas on the prairie. Seeing a place better after you have left. Hello absurdist poet — we know you well.

Leslie VonHolten writes about the connections between land and culture. A 2022 Tallgrass Artist Residency fellow, her art writing has been published in Pitch, Lawrence.com, and Ceramics Art + Perception. Sometimes she also curates a show or makes a zine. She lives in Kansas, where she mostly grew up. Leslie thanks poet Al Ortolani for the Pittsburg map and memory conversations.

![Twain in study window 1903 Mark Twain in Study Window [1903]](https://newterritorymag.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Twain-in-study-window-1903.jpg)