JOHN JOSEPH MATHEWS

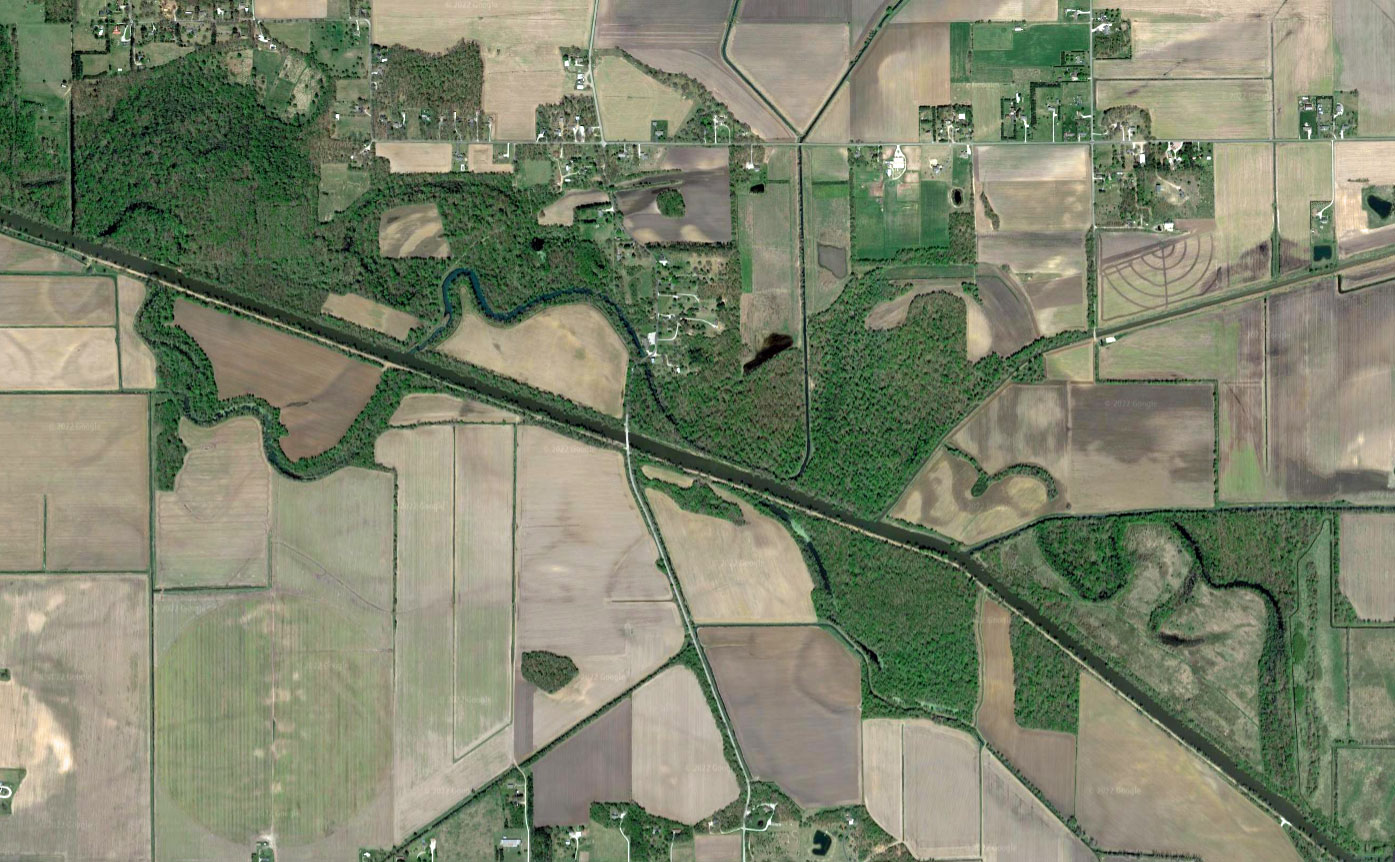

Tallgrass Prairie Preserve

Osage County, Oklahoma

By Mason Whitehorn Powell

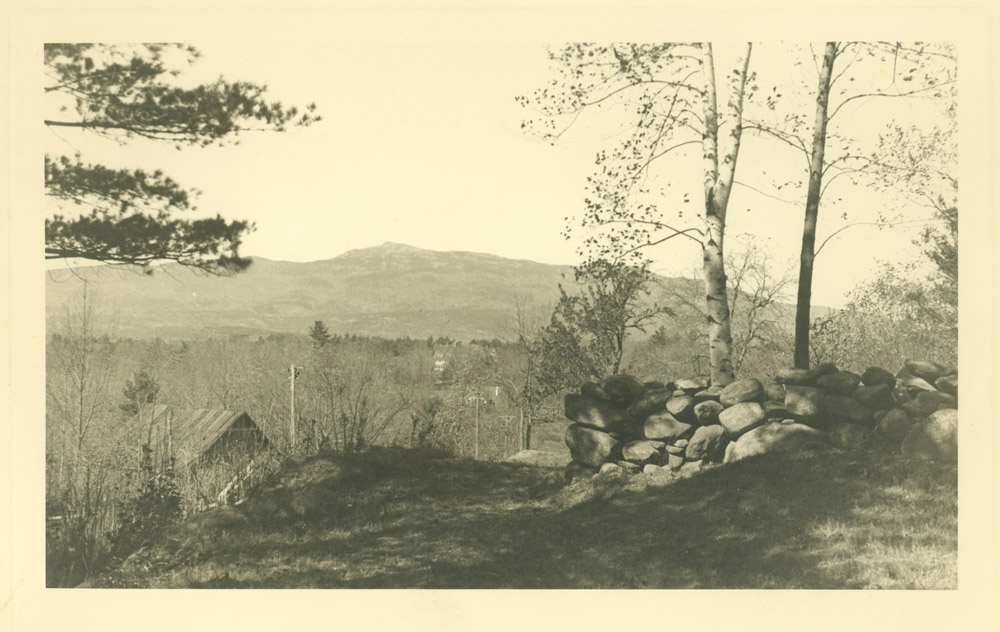

“Three ridges roughly boat-shaped push their prows south into the sea of prairie.” The opening lines of Talking to the Moon by Osage author John Joseph Mathews describe the land where he would build a sandstone cabin in 1932 to live out the remainder of his life. Published in 1945, Talking to the Moon is an intimate reflection on the landscape, wildlife, occasional tribal affairs, and seasonal changes that he experienced across this decade.

Mathews named his one-room cabin The Blackjacks, moored by those eponymous native oak trees and harbored by a sea of prairie. The cabin was abandoned after his death in 1979, and his grave remains on the property, which is now surrounded by a fence to keep roaming buffalo off the grounds. The Blackjacks and the land surrounding it were purchased from Mathews’ descendants by The Nature Conservancy in 2014 and, during summer 2020, I toured the cabin digitally, in a virtual event hosted by TNC and the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve.

I may have never seen the Blackjacks with my own eyes, but I know the world he describes because I was cut from the same cloth. After serving as a pilot during in World War I, studying at the University of Oklahoma, obtaining a degree in Natural Sciences from Oxford, and roaming around Europe, Mathews grew travel weary and was drawn back to the lands he knew intimately and loved. He returned home to allotted land on the Tallgrass prairie north of Pawhuska, Oklahoma, his birth town.

His words are familiar to me, as an Osage having the same blood quantum as Mathews, raised in Osage County, pulled between tribal traditions and the white influence upon my own life. I also studied in Europe; I met my wife there and lived in Italy for a time before returning to reside in an even older native sandstone building in Hominy, Oklahoma with family allotments not too far from Mathews’ cabin.

Mathews writes, “My coming back was dramatic in a way; a weight on the sensitive scales of nature, which I knew would eventually be adjusted if I live as I had planned to live; to become a part of the balance.” Structured by and depicting the four seasons, Talking to the Moon is subdivided according to the traditional Osage calendar: moon phases. Everything is structured as so — one only has to look. I write this as the Yellow-Flower Moon fades into Deer-Hiding Moon. Heat enters through my window and I notice that the yellow flowers growing in my yard have closed up. Behind my grandfather’s house, a doe and fawn are beginning to stir on cooler evenings, but the bucks have already vanished as hunters ready themselves.

Under this same moon, Mathews writes of driving to Hominy to meet with the old Osage men, Claremore, Abbot, and Pitts, to have their portraits painted by an artist with the Public Works of Art Project. These portraits are still on display in the Osage Tribal Museum in Pawhuska, which Mathews established in 1938. From 1934 to 1942, he sat on the Tribal Council on that same hill rising above downtown Pawhuska, where my mother also served for two terms as an Osage Congresswoman.

My grandfather never met Mathews but tells me about my family’s encounter with him:

“About half those books were given to him by your [great-great-] aunt Magella. When he’d run out of things that weren’t in a book somewhere he could study, or come out of the Catholic Diocese or wherever, then he’d have Magella tell him what had really happened. Where they came from. What families you were talking about.”

He summed up the conversation: “My dad told my aunt, ‘Don’t you be giving him any more information.’”

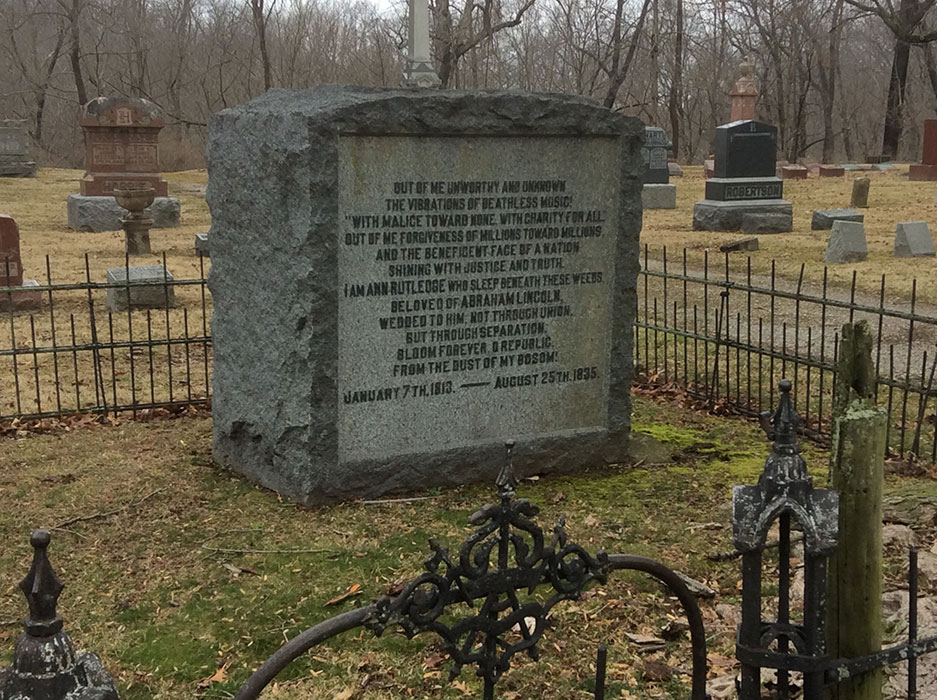

Mathews and my blind aunt Magella Whitehorn were speaking after the “old ways” were laid to rest during her father’s generation. Mathews and Magella were both born in 1894 in Osage Indian Territory, twenty-two years after our final relocation. She was a full-blood and among the last of those born onto the ground and raised with a bundle, observing the ancient Osage religion.

In the posthumously published autobiography Twenty Thousand Mornings, Mathews writes of his childhood bedroom, from which he “could look down into the valley.” From this vantage point, he could hear Magella’s father and other elders rise before dawn to greet the sun with prayers, which sounds he recounts as “the scar” of “a precocious memory.” Mathews writes, “The prayer-chant that disturbed my little boy’s soul to the depths was Neolithic man talking to god.”

In her youth, Magella was sent to boarding school and pressured to relinquish her traditional Osage identity and status grounded in our ceremonial rites. She did so because her elders said to, and it must have felt like entering an oblivion. Even though Mathews spent a career wrestling with his precocious memory of Osage mysteries — a lifelong attempt to capture and confront the past with words — there remained a painful tension between those who had to leave the old ways behind and those raised to inherit the new world. For Magella, this was a tragic episode. And her brother Sam Whitehorn, my great-grandfather, told her not to speak with Mathews because he viewed her knowledge of the past as family business.

The land speaks in indescribable ways, and our history is mysterious in its abandonment as we are adopted into a new world. It is evident in his writings that Mathews experienced a different Osage County than I know, but my generation still faces many of the same concerns, will pass down similar traditions, and can still fully experience that immutable landscape. A cabin is just a building. That was never the point—rather that it is centered, grounded, embraced by land that knows and accepts us, that is our inheritance despite ongoing changes. Lost traditions survive in both Mathews’ books and family stories such as my own. Mathews knew that Osage history must be preserved, just as land must be conserved, because the two are inseparable.

The more I learn from the rolling hills around me, the more I know about myself. Any time I drive north from Hominy towards Pawhuska, crossing a sea of prairie and islands of blackjacks, I feel at home and overwhelmed by acceptance. I haven’t needed to visit his cabin to know these things, only to truly see nature here, and to listen. When the world allows and in-person tours resume, I hope to step inside Mathews’ cabin. Until then, I have the Osage landscape and my connection to Mathews in our shared culture and his books: “with word symbols as my poor tools, to sweat at the feet of a beauty, an order, a perfection, a mystery far above my comprehension.”

Mason Whitehorn Powell is a freelance journalist based in Oklahoma and Rome, Italy. An enrolled member of the Osage Nation, his work often explores Indigenous arts and representation.

Photo courtesy of Tallgrass Nature Conservancy.

![Twain in study window 1903 Mark Twain in Study Window [1903]](https://newterritorymag.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Twain-in-study-window-1903.jpg)