R. A. Lafferty

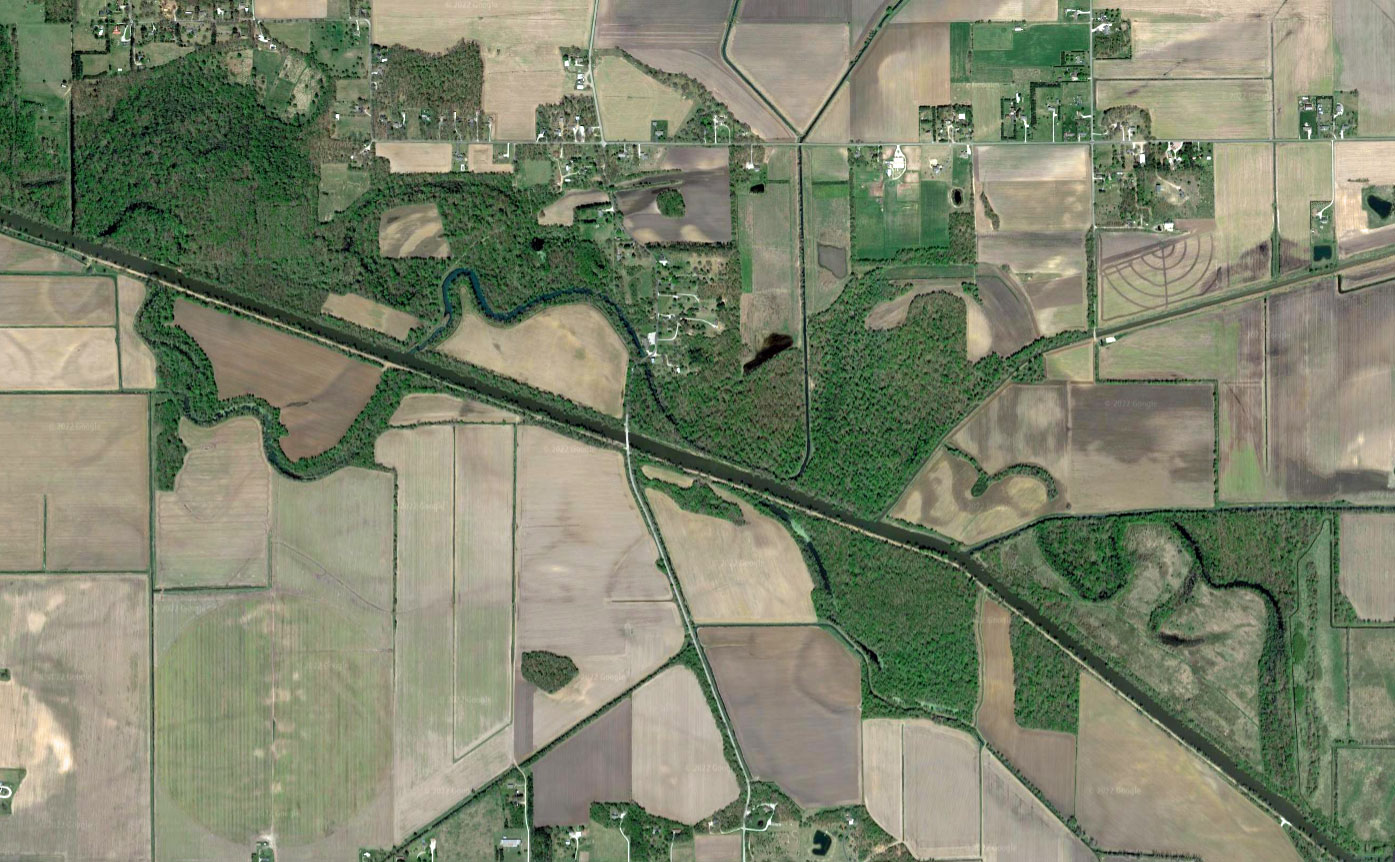

1724 S. Trenton Ave.

Tulsa, Oklahoma

By Michael Helsem

“Everything, including dreams, is meteorological.” – R. A. Lafferty, ”Narrow Valley”

A couple of years ago, my wife and I were visiting my young niece and her husband in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where they had moved — a place I had never been. At first all I could think of was that immense, windswept plain, many times traversed by me, with speeding wheels, with wings, never stopping, the very incarnation of a blur. Then it dawned on me that the science fiction author R. A. Lafferty, whom I had idolized in the ‘70s), had spent almost his entire life in Tulsa. In the same house.

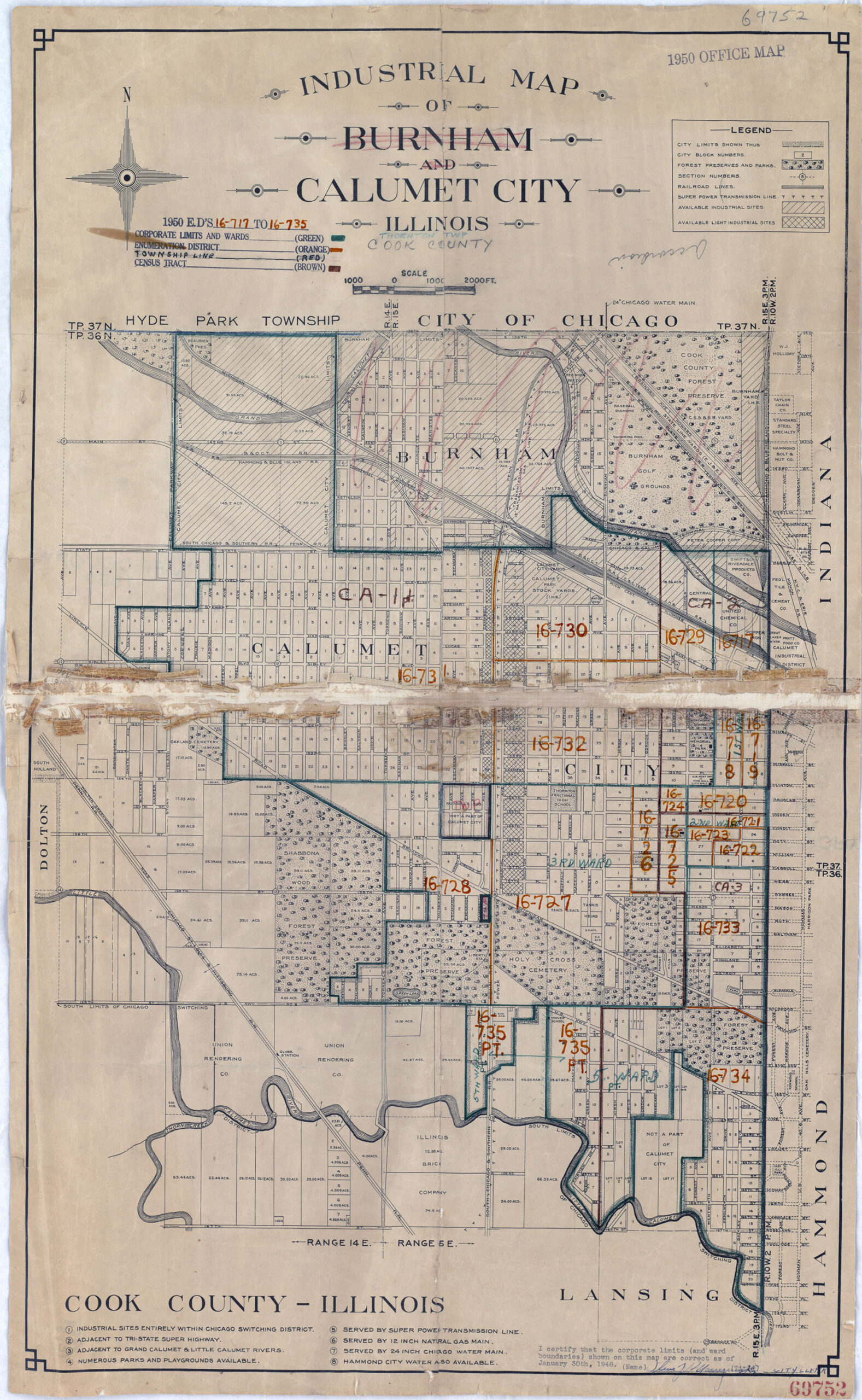

I had no luck finding any of his books in a bookstore there to show them, but at one point we were out on a walk, and I had summoned up from the Internet a not-quite-exact location of the house he had lived in. According to Natasha Ball on “Lafferty Lost and Found,” the house is “a shaded brick bungalow where Trenton comes to a T.” We went looking and found what seemed to be it, the corner house at 1724 S. Trenton Ave. I didn’t have a camera along, but it was satisfying to have seen it, anyway. It was a quiet, slightly gentrified neighborhood of older houses near a small lake, with good-sized trees on every block, which reminded me of the place in Oak Cliff I myself had grown up in — a good place to be a kid running wild on bicycles, where it seemed nothing bad could ever happen.

“Their brains differed from ours, their concepts must have been different, and therefore they lived in a different world.” – The Devil is Dead

Who is R. A. Lafferty, you may ask? He has fallen into obscurity but seems to be making a little bit of a comeback these days, praised by the likes of Neil Gaiman. To know him better, first run out and grab a copy of Nine Hundred Grandmothers. That’s a good start. Lafferty is best known for his inimitable short stories, which are only incidentally concerned with the tropes and themes of regular science fiction, and told in a jocular but slightly jarring voice that is a little like a tall tale and a little like a homegrown surrealist who has some really important things to say that he absolutely will not divulge, except in hints and sideways jokes. If you read enough of him, you start to dimly discern the vast, convoluted architecture of Lafferty’s universe—not an easy task, since so many of his books are out of print and not a few of them were published by small presses that never printed a large run in the first place.

To my understanding, there is a highly esoteric Thomist-Catholic aspect to it. He apparently also believes we inhabit a multiverse in which time and space are sometimes illusory and sometimes not; survivals from the distant past (such as Neanderthals) or visitors from the future are not unheard of—and they’re not often used for the science-fictional story, they’re just THERE. He often makes reference to obviously bogus works, yet he’s also curiously erudite in real ones. There’s a wild Zen side, too, but you never can be quite sure when he’s being serious & when he’s pulling your leg.

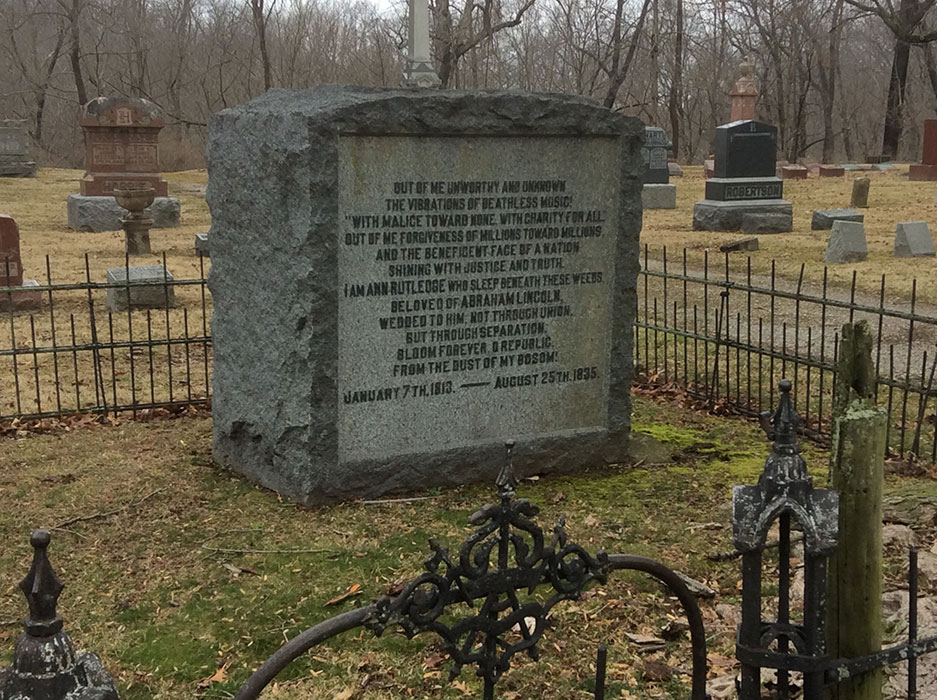

“I was always for the underdog, and, doggy, you’re way way under.” – Fourth Mansions

It’s been said that aspects of the surrounding town are always seeping into his works, and not only the more ostensibly realist ones. But by and large, Tulsa is not present in any immediately named way — any more than the environs of the great mystical poets—unless you count the almost complete absence of that most-20c. experience: riding in a car (Lafferty didn’t drive). But two things I know. One is that Lafferty always identified with the underdog, the misfit, the underclass, and the socially disfavored; he has some striking stories and one historical novel (possibly his masterpiece, Okla Hannali) about Native Americans, whom he invariably credits with greater perception of reality.

In his many worlds, there is a pervasive, bone-deep precarity: the irruption of personal and/or apocalyptic violence is never out of the question, at any moment. I have to think the terrible 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, which happened about three miles from his house (although he was only seven at the time) must have been something he couldn’t not have known about and reflected on.

“We are living in the narrow interval between the lightning and the thunder.” – Arrive at Easterwine

And then there are the tornados — 98 since 1950, according to the National Weather Service. Idyllic the place might be, but hardly peaceful. On that particular, mild, sunny afternoon, we drove past two blocks of torn-up buildings that hadn’t yet been rebuilt, havoc from the last big one. It looked like a bomb had gone off, levelling everything; the car fell silent. You see such scenes in newsreel footage, latterly Ukraine maybe: never in these States, not like this. All the other cars kept right on rolling, on to their intended destinations, untroubled and I daresay sound of sleep. They raise their families, go to their neighborhood churches, my niece and her new husband among them. This is where they choose to live.

“We could always make another world,” said Welkin reasonably.

“Certainly, but this one is our testing.” – “Sky”

M. H. was born in Dallas in 1958. Shortly afterwards, fish fell from the sky.

Photo by Abby Boehning.

![Twain in study window 1903 Mark Twain in Study Window [1903]](https://newterritorymag.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Twain-in-study-window-1903.jpg)